Idea Maps: Breaking New Ground

27 Jan 2025

A novel combination of citizen science and mapping analytics promises to deliver a new perspective on some of the most disadvantaged urban areas on earth. Urban Realm speaks to the University of Glasgow to see what promise the system holds for slum upgrading.

Some of the poorest places on the planet are being put on the map through the power of a novel crowdsourcing tool which, combined with citizen science, is propelling participatory urban analytics into uncharted territory.

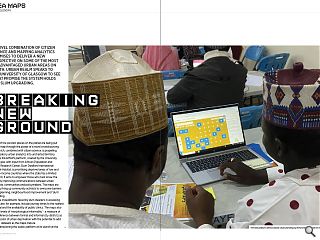

The IDEAMAPS platform, created by the University of Glasgow with input from African Population and Health Research Center, Slum Dwellers International and UN-Habitat, is prioritising deprived areas of low and middle-income countries where the state has a limited footprint. It aims to empower those who best know the areas by improving communications between urban scientists, communities and policymakers. The maps are already firing up community activists to overcome barriers in city planning, neighbourhood improvement and ‘slum’ upgrading. The impediments faced by slum dwellers in accessing healthcare, for example, include journey times to the nearest hospital and the availability of public clinics. The maps also record levels of ‘morphological informality’ - a measure of the difference between formal and informal city districts as an indicator of urban deprivation with the potential to add further datasets as the maps mature.

Championing the public platform at its launch at the World Urban Forum in Cairo Professor João Porto de Albuquerque, chair in Urban Analytics at the University of Glasgow, told Urban Realm: “There are a lot of top-down approaches, especially in the global south. There are data gaps, especially in urban areas which prompted us to look at development in a more participatory way. A lot of residents of these informal areas are not taken into account in policy. “IDEAMAPS connects communities with data and enables them to take ownership and contribute. We can improve the data over time and make it more useful. That’s why we are launching it here. We have developed this with policymakers in pilot cities across Nigeria and Kenya, it is open for public scrutiny and feedback.” Initially documenting Lagos, Kano and Nairobi coverage will be extended to additional cities later this year, with additional dimensions of deprivation also promised for inclusion to build the fullest picture possible. “There are several approaches to deprivation”, notes Albuquerque.

“We use parameters which are locally relevant and can be actioned by policymakers to improve conditions.” How do you manage the data gap when working in disadvantaged areas, where online access is presumably limited? Albuquerque answers: “We work closely with community leaders, it’s a simple tool they can contribute to and validate. We also have organised sessions in which community leaders gather with groups of people, then we have the inclusion of members who are not as technically savvy through participatory action research groups. That was our strategy to reach beyond community leaders to other parts of the population.” Models are only as strong as the data that underpins them. How do you seed this model? Do you gather data in advance to populate the platform or is it a blank slate? “We take the best available data but usually it has gaps. Using modelling, artificial intelligence and satellite imagery a best estimate can be obtained for the levels of deprivation. After that committee members can validate, calibrate and improve.”

What response has the team from the University of Glasgow found on the ground? Has the response been sufficient to generate an accurate model? At what point can you confidently say this is a true reflection of the reality on the ground? If numbers are low could this leave the system vulnerable to a concerted campaign to skew figures along political lines and is there any policing to ensure the process is going as you would wish? “We have hundreds of responses but we have a snowballing strategy, starting with some communities and then expanding. We can run tests to assure stakeholders of the veracity of information.” Another variable impacting accuracy is the choice of 100m grid cells, is this enough to give sufficient granularity to identify deprivation hotspots? “100m is a good compromise”, says Albuquerque.

“It gets under the block level but doesn’t disclose the borders of some communities. We did this because of worries that this data could be used to justify evictions and other harmful actions. Obfuscating boundaries was useful for them and that was part of our rationale. It makes it much more manageable to click, as you can assume that in 100m variability of deprivation parameters is not very high and that is what we have seen in practice.”

More than a tool for planners the maps are a way to engage with the most vulnerable and disenfranchised members of society, people who have historically been disconnected from governance. Do people see the benefit? A system like this may perform well in a middle-class neighbourhood with an educated population willing to engage politically. Is this a way of democratising the delivery of services and giving people a voice who wouldn’t otherwise be heard? “We have had strong feedback that this is useful for them when advocating for improvements in water, sanitation and electricity, roads and homes.”

Are approaches developed here applicable closer to home, is there scope to involve Glasgow or other cities in the west? “I do think there is potential. Participatory urban analytics data can be remote from people’s lives. This way of visualising and representing data closes that gap. We are interested in expanding this to other cities, including in Scotland, using the current framework.” We are all creatures of our environment and take pride in our surroundings, even in suboptimal circumstances. A social model taking account of people’s lived experiences that harnesses community networks without relying solely on impersonal metrics is long overdue. Only by enabling people to bring order to chaotic spaces can these informal urban areas be integrated into the wider infrastructure of the city. Frequently neglected in policy and decision-making, the lives of residents can be better fulfilled with improved access to basic services when they take matters into their own hands. If demography is destiny then planning is power.