Arrochar Torpedo Range: War & Peace

27 Jan 2025

Revisiting arguments around the provision of amenity in loch long pre-Faslane Mark Chalmers explores the issue of redundant military land and the challenges of remediating a brownfield site in a national park.

The challenges of building in Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park were highlighted by the recent tug-of-war between developers Flamingo Land and amenity campaigners. The proposed Lomond Banks development at Balloch was rejected by the park authority in September 2024, and afterwards the newspapers used dog-whistle language, such as “mega-resort” and “David against Goliath” battle. Just as there is a formula for developing leisure resorts, there’s a well-worn lexicon which tabloid hacks fall back on. The coverage received by Lomond Banks barely addressed the underlying issues, which are significant. At their heart lies a contention about who, and what, a National Park is for.

It’s a managed environment with grazing, economic forestry and fisheries where country folk make a living. It’s also a playground where tourists and city folk go hiking, hunting, wild camping and mountain biking. Seen through the other end of the periscope, it’s a testing ground for the armed forces. Should the National Park aim to attract visitors – or actively discourage them, as the National Trust for Scotland has done at Ben Lawers? Can we improve it by providing better facilities, for locals and visitors alike? Or are National Parks so precious that we shouldn’t touch any part of them – even the polluted and abandoned sites which have lain unused for decades?

Another development site on a different loch within the National Park provides an alternative set of answers to those questions. If you think property development around Loch Lomond and The Trossachs is a risky enterprise, try creating underwater missiles packed with high explosives. In 1866, Robert Whitehead developed the first torpedo whilst working at Fiume – now Rijeka, in present-day Croatia. He introduced the world to a weapon that changed the course of history, by arming submarines which sank millions of tons of shipping during the World Wars. The Royal Navy was quick to see its potential, and in August 1907 the Argyllshire Standard reported plans by the Admiralty to build a torpedo range at the head of Loch Long. Locals grew alarmed that the area would be taken over by the military, to the detriment of water quality, fishing and tourism. Even in those days, tourists were a big moneyspinner, thanks in part to the Caledonian Steam Packet’s steamers which called at piers along the loch. Concern about pollution in Loch Long and nearby Loch Goil began well before the torpedo range.

The problems were man-made: dredgings from Glasgow Harbour were dumped at the southern end of Loch Long and 150 tons of effluent from Charles Tennant’s alkali works made the same trip each week. The Clyde brought down Glasgow’s sewage which flowed into the tidal waters of the loch, mixing with run-off from houses along the shore, while soot from the steamboats settled on the surface. The Admiralty selected a site on the loch’s western shore, directly opposite the village of Arrochar. The large number of objections to it prompted Argyllshire County Council to file a formal objection – bearing in mind this predates the Town Planning system by 40 years, and the National Park by a century – but their protests were dismissed. In 1908, a construction contract was let to Sir Robert McAlpine, and the first part of the torpedo testing station was handed over to the Admiralty in 1912. The concrete jetty at Arrochar is a very early example of a reinforced concrete structure, designed by F.A. MacDonald & Partners of Edinburgh and built by McAlpines around 1915, then torpedo testing began at pace. Unarmed torpedoes were lowered into launch tubes under the range control building, fired down Loch Long towards a line of floating targets, then recovered by a launch so that they could be trimmed to run straight and true. The military calibrates risk in a different way to the rest of us. For example, an anecdote from Field-Marshall Slim’s memoir “Defeat into Victory” has him cheerfully sending 40-ton tanks over Burmese bridges with a 20-ton weight limit, on the basis that they would have been massively over-engineered by the Victorians who built them. Similarly, locals in Arrochar often watched out-of-control torpedoes fetch up on the loch shore, although when a prototype Mk.12 torpedo exploded at Arrochar, the programme was cancelled. This time, the risks were too great, even for the Admiralty. Arrochar worked in parallel with the Torpedo Factory at Alexandria, and development was also carried out in the hydrodynamic testing tank at Glen Fruin, which I wrote about in the Spring 2012 issue of Urban Realm. Many types of torpedo were developed, but the range closed in November 1986 since the loch wasn’t suited to more advanced designs such as the Tigerfish, which ran much faster and deeper.

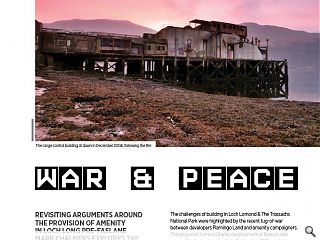

While the Victorians were concerned about the impact of the torpedo range, decades later we’re bothered by the blight it left behind. The range is a rare brownfield site within the National Park, and today all the value seems to lie in its location and the glorious views down Loch Long. After closure, Defence Estates sold the range buildings to a developer which recognised the site’s potential, along with an under-provision of hotel rooms in the area. Arrochar is a wayside village with a handful of hotels, but little in the way of restaurants and attractions. In a sense, it’s the opposite of a tourist trap: people pause for the view then keep driving. In recent years the village has also become a hostage to fortune: each time a rockfall closes the A83 at the Rest & Be Thankful, Arrochar sits isolated while bulldozers battle to re-open the road. While the torpedo range’s new owner considered how best to redevelop them, the abandoned buildings attracted vandals and fly tippers – then they were overtaken by events. Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park was established in 2004, which raised many questions. Would that make it easier to deal with problem sites like the torpedo range – or more onerous to allocate sites for development? Demolition work began in June 2007, but a month later a fire destroyed many of the buildings and the torpedo range was left smouldering on the lochside. In the meantime, the 1960’s youth hostel at nearby Ardgartan had also been abandoned. It was demolished in 2009 and a new 124-bedroom hotel for coach parties opened the following year: it’s a five-storey block which looks vaguely like a Victorian-era Hydro hotel. Suddenly the redevelopment of the torpedo range had competition, and that changed the business case for the planned hotel and leisure development. In an effort to differentiate itself, the Ben Arthur Resort scheme was born.

As Kevin Cooper of NORR (at that time Archial NORR) explained to me, they were approached around 2012 by a residential developer they’d worked with before, who had acquired an option on the site. Archial worked up a scheme for a 130 bed five-star hotel, timeshare apartments, a chandlery and café bar on the loch shore – plus dwelling houses and an extensive marina. The initial proposal took the form of a contemporary castle clad in grey zinc and local stone, punctuated by projecting bays and cantilevered upper levels. It was developed into a series of wings with rooms angled to maximise views down the loch towards the setting sun. The scheme was well received by the Planners and the application was approved in 2013. Kevin Cooper explained that, “We had a few positive sessions with the locals in the community hall, but they were very sceptical about it going ahead. I don’t think they really believed us, and I guess ultimately they were right.”

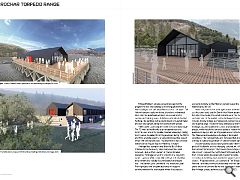

The development formula at Ben Arthur was high input and high output: the infrastructure costs were considerable, but the resort was intended to be high-end, serving everyone from hillwalkers hiking in the Arrochar Alps, to wealthy individuals flying in to Glasgow then heading north to explore Rob Roy country. Kevin Cooper is sanguine about the scheme’s fate, further explaining, “It really was a joy to design, but the best things often don’t get built, do they? Wonderful site though; probably the best I have ever encountered.” After the Ben Arthur Resort fell through, the site was subsequently sold and lay fallow for several years. The torpedo range remained as a tantalising opportunity, then the site was advertised for sale again in 2021 and bought by Ardnagal Estates, three local investors with a background in commercial and residential property. A new project was brought forward by architects Framed Estates in 2022, with a Planning application lodged last year which is currently being considered by the National Park authority. Framed Estates’s scheme concentrates part of the programme into two buildings with strong gabled forms: a Hub building on the pier, and a Bunkhouse on the shore.

The Hub will contain a café, workshop, chandlery and general store, and the Bunkhouse will have 20 en-suite rooms, canteen and training space. In deference to site’s industrial heritage, the buildings will be clad in black corrugated metal and red fibre cement, along with Scottish larch panels. Views down Loch Long aren’t the site’s only advantage. The 110 year-old north jetty is an untapped resource. Arrochar was one of the paddle steamer Waverley’s calling points when she sailed from Craigendoran during the 1950’s and ‘60’s, and she recently re-visited Ardnagal Pier as part of her 75th anniversary tour. The intention is that Arrochar will become a regular stop for Waverley in future.

Ardnagal has a simpler brief than the Ben Arthur scheme did, as the luxury hotel component has been removed – but as Chris Hudson of Framed Estates explained, “Ardnagal solves the problem of a long-term, derelict eyesore while potentially solving local amenities, employment and holiday accommodation shortages too.” The current Loch Lomond & The Trossachs Local Plan highlights that the park authority will support developments in the countryside where they support economic activity, so the Planners remain supportive of redeveloping the site. While the youth hostel at Ardgartan was redeveloped as a four-star hotel, and the Ben Arthur Resort proposed a five-star hotel, today the unmet demand lies in the middle and lower end of the market, so the Ardnagal scheme also includes holiday lodges, glamping pods, campervan pitches and a games area. The bunkhouse addresses a shortfall of budget accommodation for school and backpacking groups, while the pitches are anticipated to reduce the pressure on lay-bys and parking areas around Arrochar. The Planners acknowledge a shortage of dedicated amenities in the National Park, and it’s hoped that Ardnagal will help to reduce the problem of rubbish-strewn verges.

Accommodating tourists alongside locals in the wilder parts of Scotland is an ever-changing conundrum. While the Lomond Banks project risked over-developing a prime site on Loch Lomond, the North Coast 500 route suffers from chronic under-development: it lacks the hotels, campsites and parking areas needed to support summer visitors. Proposals within Loch Lomond & The Trossachs National Park have evolved considerably over the past 20 years, and while Lomond Banks was torpedoed, hopefully the Ardnagal project achieves equilibrium in 2025.

|

|