East Calder Primary: Breaking the Fourth Wall

27 Jan 2025

A new primary school in east calder is pointing the way ahead to energy-conscious education but is its one-of-a-kind design a harbinger of things to come? Urban Realm assesses how it’s shaping up. Photography by Keith Hunter.

A series of newly built schools across West Lothian is offering an object lesson in how to educate efficiently when condensing learning to a single deep-plan building, as exemplified by the hangar-like West Calder High. Urban Realm visits its little brother at East Calder Primary to see if it is the right angle to take.

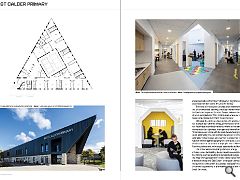

Fly over the Lothians and amidst the morass of new housing one building stands out, a geometrically-perfect structure which points the way forward for East Calder’s Main Street. Fitting snugly within the bounds of the existing school and resembling a Stealth fighter, East Calder Primary raises its hat to pupils, staff and the community at large from its southwestern prow, which also frames a retained Early Years Centre. Built a decade ago it is the only element of the old school to be retained and frames the courtyard at the new entrance.

The old school, currently in the throes of a painstaking demolition process following the discovery of asbestos, takes up most of the site, limiting outdoor space to a narrow landscape strip to the south and east. Soon, this will expand significantly with new playing fields and ample open space replacing the old school. Completed by Hub South East and Morrison Construction to designs by Norr the fixed price £18.3m build was ordered by West Lothian Council to help meet the challenges presented by its fast-growing population, one of a series of schools by the same team that includes Calderwood Primary, West Calder High School and the Winchburgh Schools Campus. Population predictions show the number of people calling West Lothian home will continue to rise from 183,820 in 2020 to 203,320 by 2043. The distinctive geometry has been governed by a desire to minimise the ratio of external walls to internal floor space, thus improving energy performance and reducing its carbon footprint - critical concerns now that the Scottish Futures Trust funding criteria are driving a new wave of low-energy schools.

More than a teaching aid for Pythagoras’ Theorem the three-sided design aims at compactness, with Norr director Kevin Cooper, telling Urban Realm: “Nothing is very far away, the building is only 40x40m.” Additional benefits flow from the optimisation of connective spaces, eliminating hallways almost entirely in favour of a series of interconnected rooms and spaces. “Why waste space on circulation?” Cooper asks. “Everywhere is a learning opportunity.” The three points of the school are natural focal points, that lend themselves well to a covered main entrance and reception area that channels people inside. The other vertices house a learning space devoted to Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics and a ‘nurture’ area for children behind a double-glazed facade, painstakingly inserted by Morrison. Cooper observed: “A primary school by its nature is a bit more cellular but it does have these activity spaces.”

The Euclidean geometry extends to an efficient roofscape, sadly only visible to drone operators, with the simple shape serving to minimise maintenance and rationalise drainage. The form also delivers the wow factor through a functionally efficient spatial arrangement that is aesthetically beautiful, though only from privileged vantage points, the building betrays no clue to its unorthodox floor plan when viewed face-on. By Inspiring teachers and pupils to think outside the box the school meets aspirations for a dynamic community presence that stands out from the crowd without choking off daylight to the interior. This is achieved By opening up end-to-end circulation routes unencumbered by fire doors or blank walls. Maximising every square centimetre of the 3,545 sqm floor space the spinal routes include reading nooks and are cluttered only by the occasional bin or fire extinguisher. Openings onto the main dining hall and learning stairs further accentuate the sense of space and include ready access to a mixture of flexible collaborative and individual workspaces as well as outdoor play and learning. A deep plan inevitably raises the question of how to handle the interior, with the team arranging classrooms around a multi-use games hall rather than a low-utility courtyard or a cacophonous dining hall. Half the skill in delivering a public sector project on this scale is choosing which battles to fight, with Norr constructing its trenches around perforated wooden wall panels.

The acoustic device stands out amidst the painted plasterboard though Cooper expressed annoyance at a misaligned window detail. Proud of the overall look Cooper added: “It avoids the overly clinical finish of most newly built schools. It does three jobs, it’s robust, aesthetically pleasing and acoustically performing. Individually it might be an expensive item but overall it’s value for money.” The limits of a fixed price contract show elsewhere in the use of sinusoidal cladding, offset by a harder-wearing buff brick to the ground floor but Cooper believes the team struck a good balance: “It’s a tight budget where we had to make some choices but I think it’s appropriate.” Ultimately the defining characteristic of the school is not its shape but rather its energy performance. While not Passivhaus accredited the school makes all the same moves around air tightness, solar gain and thermal bridging.

“Orientation was critical with the main facade facing true south, eliminating the cold northern facade and optimising solar gain,” notes Cooper, who went on to stress that he was not entirely against applying for a wall plaque, despite remonstrations from some on the project team. “We’ve done Passivhaus elsewhere, we’re equal opportunity architects!” One of the fears surrounding a focus on energy efficiency was that building design would descend into a box-ticking exercise resulting in standardised designs but the three-pronged approach to East Calder belies that idea. Instead of asking why East Calder is triangular perhaps the real question is why aren’t all buildings triangular? In a world of identikit ‘superblocks’ it is refreshing to see a new school break the mould.

|

|