Woodmill & St Columba's: Nested Learning

8 Nov 2024

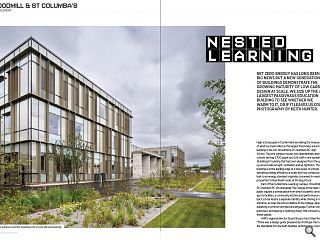

Net zero energy has long been big news but a new generation of buildings demonstrates the growing maturity of low-carbon design at scale. We size up the UK’s largest passivhaus education building to see whether we warm to it, or if it leaves us cold. Photography by Keith Hunter.

High school pupils in Dunfermline are taking the measure of what has been billed as the largest Passivhaus education building in the UK: Woodmill & St Columba’s RC High School. The joint campus houses two operationally distinct schools serving 2,700 pupils and 246 staff in one sprawling 26,666sq/m building that has been designed from the ground up around natural light, ventilation and air tightness. The building is at the leading edge of a new wave of schools delivering energy efficiency at scale, but how conducive is their bulk to an energy standard originally conceived for residential properties?

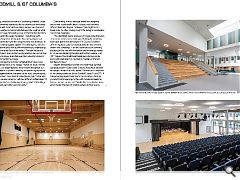

Urban Realm looks at the big picture. Part of the Dunfermline Learning Campus, Woodmill & St Columba’s RC sits alongside Fife College at the head of a public square, a pivotal place from which students can access sports facilities, a community kitchen and performance space. Each school retains a separate identity while sharing a main entrance, as does the school relative to the college, despite adopting a common architectural language. Further unity of purpose is provided by a ‘learning street’ that connects each of these spaces.

AHR’s regional director Stuart Bryson told Urban Realm: “There was a design guide prepared by Architype that set the standards for how both facilities, unfortunately, procured separately, should look in terms of positioning, material choice and environmental standards. We ran architecture workshops in tandem with Reiach and Hall taking design cues from each other. We wanted a commonality between the buildings while each does its own thing with a visual connection that ties them together within the wider masterplan - including a north-to-south rain garden. At one point there was going to be a physical connection with the college but that was dismissed in favour of creating a public square.” This nesting of school and college has influenced the accommodation style, emphasising collaborative study. Bryson remarked: “The learning lab is a different type of space to that usually used by Fife Council, they see it as a crossover space between their education style and pupils moving into the college.”

“You can see the vertical emphasis and banding on our school that ties back to the college. There is no doubt that the college is a far bigger building. We are lower and spread out for educational purposes. Ultimately, we parted slightly on our different approaches but certainly, at the start, everything was done in tandem. It was Reiach & Hall director Lyle Christie who said: 'We are one carpet but with two different coffee tables.' It stuck in my mind as a lovely way of saying how both buildings complement each other and sit in unity.”

Commenting on the challenges inherent in designing around two operationally distinct schools, each running a different timetable, Bryson continued: “One might be on a break while the other is being taught, this brought considerable operational challenges. “The client brief was to open everything up, including types of accommodation and technologies. Pushing for something more open plan is new territory for Fife Council. To deliver different types of space for two headteachers who are very thrawn was a challenge. Then the technical side of delivering a building of that size with low carbon and low energy figures to hit, we were bettering the RIBA and Scottish Futures Trust (SFT) figures. More traditional Passivhaus schemes can be a box with small openings, we tried to maintain a different architectural style.”

Eagerly anticipating the arrival of a Passivhaus-certified wall plaque later this year Jamie Gregory, Passivhaus designer and project architect at AHR, added: “Passivhaus is a response to the funding criteria set by the Scottish Futures Trust (SFT). A school building doesn’t lend itself to be Passivhaus because you want to limit openings to the north facade and keep the form as compact as you can.” Despite this, the school achieves a form factor (the ratio of exterior surfaces to floor space) of 1.7. This efficiency in reducing surface areas from which heat can escape is achieved by running two blocks from east to west. Gregory adds: “Orienting principal elevations to the north and south allows you to control overheating with brise soleil, it minimises elevations to the east and west with vertical fins on the curtain wall facades. It’s harder to control overheating on those elevations so the school minimises those. Early design choices in orientation, form factor and stacking accommodation and frames allowed us to drive a Passivhaus-compliant building.” With every pupil giving off around 100 watts of energy that’s the equivalent of approximately 270kw of free energy for the school without needing to go anywhere near a radiator thermostat. Discussing the issues in meeting sustainability challenges at scale Gregory added: “Delivering Passivhaus on a building of this scale rather than a house adopts much the same principles. If you work with Passivhaus principles from day one it does ease the delivery. The contractor had a lot to do with that. Steel frames are prevalent on Passivhaus buildings in Scotland and we’ve just started a steel frame school in Rosyth for Fife Council, but when this began it wasn’t a known technology for delivering Passivhaus.”

Instead, the school utilises a concrete frame for both teaching wings, linked by a steel frame reception area and joined by a sports block to the south which adopts yet another approach owing to more onerous span lengths and ground conditions; cross-laminated timber. “If you can introduce air tightness from day one then you’ve derisked the delivery of an air-tight envelope”, says Gregory. “What that means is effectively the whole wall is airtight, you are only dealing with the window and door openings.” This was partly down to logistical concerns as the cranes needed to be inside to build the concrete at either side, plus the lightweight dining and assembly hall couldn’t be built in concrete. Furthermore, the steel provides additional lateral support to the concrete. While the sports block went with CLT predominantly on embodied carbon grounds AHR were more than happy with the choice: “The internal aesthetics suited us, we would have had the whole building in CLT if we could have got away with it. The contractor did not want to do the entire building in steel because of the price at the time. The concrete suited them to reduce their air tightness risk,” says Bryson.

“Three different structural frames meant three contractors and suppliers were all on-site together. BAM split their risk in three ways.” The school is subject to onerous standards and performance criteria, such as a maximum of 0.6 air changes per hour, each of which must be evidenced not only in terms of embodied carbon but also operational and construction energy usage to the satisfaction of Rybka. It’s one thing to understand how something might work on paper but quite another to see the reality. Bryson remarks: “BAM is collating their construction information to demonstrate we built it as per the design. Local authorities have embraced Passivhaus because of the quality of build certification and the comfort that comes from the verification process.”

Rose Jenkins, director of estates at the University of Dundee, also stepped in as an independent design champion to ensure that delivery accorded with the agreed masterplan. As a process of agglomeration sees schools move on from teaching space to designing a self-contained community Woodmill & St Columba’s RC might be the biggest for now but not for long as other councils seek to scale up schools. Says Bryson: “It’s about the next 20 years of running costs not whether it’s slightly more expensive to build just now. Fife Council are challenging contractors’ supply chains as to why it is so expensive. Good design doesn’t cost. We’ve been through the mill on this, we’ve done it. We can take that knowledge and apply it to future projects.”

As a pathfinder project for the Scottish Government’s net-zero targets and with other local authorities such as Argyll and Bute and East Ayrshire already looking at jumbo campuses of their own the day will soon arrive when Passivhaus is the default, not the exception, but for now Dunfermline is in a class of its own.

|

|