Skopje: City Gate & Wall

7 Nov 2024

Rebuilt as a modernist utopia in the 1960s following a devastating earthquake the city of Skopje, Macedonia, had lost its shine come the 21st century. Rather than pursue demolition however the Skopje 2014 project gave many buildings an extraordinarily kitsch post-modern makeover. Mark Chalmers looks at the parallels with Cumbernauld town centre and the lessons to be drawn on how to care for modernism in the face of public apathy and political opposition.

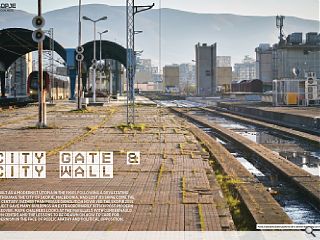

It’s 5.30 in the morning and the mountains which encircle the city of Skopje are silhouetted by the rising sun. North Macedonia’s capital is still asleep, but as I approach the main railway station, a man wearing combat pants strolls over from the taxi rank to introduce himself. His name is Sasho Trajkovski. He hands me his card, tells me he worked for NATO during the Balkan Conflict in the 1990’s, then reels off tourist attractions which are a short ride away. He’s polite but persistent: Vodno Mountain and Matka Canyon are spectacular in the springtime. I shake my head, because I’m here to see the railway station.

Skopje is an ancient city but at its heart is a 1960’s Metabolist megastructure designed by the Japanese architect Kenzō Tange, where pedestrians, trains, cars, buses and eventually trams were intended to converge on separate levels. When it was built, Yugoslavia was a country of 22 million people and international services connected it to Greece, Italy, Hungary and beyond. Today, North Macedonia is a nation of two million and its station serves a handful of regional trains each day. Sasho explains that the station’s fate is symbolic of the Balkanisation of his country into ever-smaller statelets, following the collapse of Yugoslavia and resulting war. But that conflict wasn’t the first disaster to hit Skopje.

On 26th July 1963, the city was devastated by an earthquake. Around 1,200 people were killed, another 3,500 were injured and the majority of the city’s population was left homeless. The day after it struck, President Kennedy sent a 120-bed hospital across the Atlantic in a squadron of C-130 aircraft, and a battalion of Soviet military engineers arrived to assist the rescue effort. A United Nations resolution later noted with satisfaction that, “The spirit of international solidarity demonstrated on this occasion has transformed the reconstruction of Skopje into a real symbol of friendship and brotherhood among peoples.”

The initial clean-up was followed by an international initiative to help Yugoslavia rebuild the city, led by the French planner Maurice Rotival, Warsaw’s city architect Adolf Ciborowski who drew up the social survey and regional plan, and Athens-based Constantinos Doxiadis who worked on housing, transportation and infrastructure. With the groundwork underway, a design competition was launched to masterplan the city centre. In 1964, Kenzō Tange was invited to participate by the United Nations, along with three other international teams and four teams from Yugoslavia.

The jury eventually decided to award 60% of the first prize to Tange and 40% to the Croatian team of Radovan Miščević and Fedor Wenzler; that split decision meant Tange’s vision would never be fully realised. Few projects of the time were as ambitious as the Skopje City Centre Masterplan. The aftermath of the earthquake provided an opportunity to start from scratch, with the same tabula rasa offered by Cumbernauld New Town’s greenfield site, or the bombsite on which the Barbican Centre was constructed in London. Tange’s concept embodied two elements: the City Wall and the City Gate. While they invoke a medieval walled city, the Wall and Gate were actually Metabolist megastructures intended to significantly increase Skopje’s density. The City Wall was conceived as a horseshoe of modular housing blocks which would encircle the city centre, linked by aerial bridges and cylindrical service towers. The City Gate was a transportation and cultural node intended to serve a city which would eventually double or triple in size. Had it been realised in its entirety, the City Gate would have become the integrated megastructure which Reyner Banham dreamed of at the start of the 1960’s. Perhaps Louis Kahn and Anne Tyng’s 1960’s scheme for Philadelphia in the United States could have come close, had it been built: the circulation of vehicles and pedestrians was a design driver there, too, and Kahn envisaged drum-shaped parking structures interspersed with triangular, space-frame office blocks.

Across the Atlantic, Geoffrey Copcutt’s original scheme for Cumbernauld Town Centre, with penthouse flats at the top plus offices, hotel, shopping mall, community facilities and a bus interchange at ground level was schematically similar to the City Gate. Tange’s masterplan extended Skopje city centre by bridging the Vardar River which splits it in two, with a 20th Century core lying to the south, and the Old Bazaar to the north. He intended that both riverbanks would be developed, recasting Skopje as an Open City with a megastructure at its heart. Instead, the masterplan was compromised by budget, politics and partisan interests; in the end, the only building realised by Tange himself was the Transportation Centre component of the City Gate. Kenzō Tange designed an elevated railway station with 10 tracks, its platforms sheltered from end to end by vaulted metal canopies. With its deck raised above the city on a grid of concrete piloti, the Transportation Centre has the presence of Hans Hollein’s aircraft carrier in the prairie wheatfields, while the undercroft below feels like the Hypostyle Hall at Karnak.

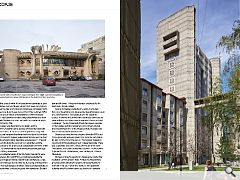

Thus the rich language which Tange developed incorporates Egyptian architecture, the medieval walled city, Metabolism from his native Japan, and the megastructural concept championed by Reyner Banham. Today, the accommodation under the deck is occupied by a sports bar, post office and a greasy spoon which sells a savoury pastry known as a burek, which looks like a flaky Forfar bridie. But the Transportation Centre didn’t fulfil its potential: Macedonia’s international trains vanished in the 1990’s, and Skopje’s citizens rejected trams in a referendum a few years later. Nevertheless, what was built is just enough to see the promise of what might have been. Other projects within the masterplan were awarded to local practitioners, such as Macedonian architect Janko Konstantinov. His towering Telecommunications Centre was completed in 1974, followed by a drum-shaped Central Post Office building in 1980. The first, unbuilt version of Konstantinov’s scheme followed Tange’s masterplan to the letter: a large plaza would have been lined with Metabolist service cores and horizontal blocks which tied into the City Wall. The plaza was discarded in a re-design, and the Telecommunications Centre became a fortress-like block with bold stair towers.

Konstantinov later explained to a Yugoslav architectural magazine that the arched ground and fourth floors were references to “Balkan medieval monasteries and churches,” while the whole building “resembles a space station.” The post office with its distinctive crown of concrete antlers was the second phase of the project, built a decade later at the end of the 1970’s. Its counter hall was destroyed by fire several years ago and is still lying abandoned. The residential blocks of the City Wall or Gradski Zid were built between 1967 and 1976 by a syndicate headed by the architects Bogacev, Simoski, Serafimovski and Kjoseva. A new boulevard had been built to circle the city centre, and the portion of City Wall built alongside it follows Tange’s concept faithfully, its eight storey linear blocks punctuated with expressively Brutalist stair and lift towers. A fragment was also constructed to the south, but it stands isolated. Several kilometres outside the city centre, the Student Dormitory Goce Delčev was designed by Georgi Konstantinovski and Zivko Popovski in 1969 and built over the course of a decade. It consists of four tower-and-slab blocks connected by aerial walkways, each like a stamp hinge which frames a central quadrangle.

The bold treatment of bush-hammered concrete on the façades, and the arrangement of four towers rotated around a pinwheel, hints at the influence of Paul Rudolph, who Konstantinovski studied under at Yale. Skopje’s reconstruction was ongoing during the 1970’s, but money grew tight and work ground to a halt in the early 1980’s. By 1991, Communism’s time was up. The Yugoslav federation dissolved and Macedonia became an independent state. There was a diplomatic crisis with Greece over the use of the name “Macedonia”, so the new country first became FYROM (Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia), then the Republic of North Macedonia. Perhaps contrary to expectation, Skopje grew rapidly after the Balkan Conflict ended in 1995. While some Macedonians emigrated, many others left the surrounding countryside for a new life in the city. Investment flowed in, then apartment buildings and office towers sprang up, leading to a period of unfettered land and property development which became known as the “Wild East”.

The new market economy had no interest in Metabolist architecture, so Tange’s masterplan gave way to generic shopping malls and apartment blocks. This laissez faire approach to planning ended in 2006, when the nationalist Nikola Gruevski became Macedonia’s Prime Minister. A friend and political ally of Hungarian president Viktor Orban, Gruevski spent the next decade promoting his Skopje 2014 plan. The city’s face changed for the third time in half a century, following the post-earthquake reconstruction of the 1960’s, then the free-for-all of the late 1990’s: green spaces were cleared to build office blocks, and government buildings were re-clad with neo-Classical facades. Like the Antonine Centre in Cumbernauld, they were designed to mask the megastructure. For Gruevski, Skopje 2014 was about re-discovering and celebrating Macedonia’s national identity, laying claim to Alexander the Great and the trappings of the Ottoman Empire. If you visit Skopje today, you’ll discover that his megalomania translated into the construction of a giant triumphal arch, huge bronze lions and a gargantuan warrior on a rearing horse in the centre of Macedonia Square. Bizarrely, the streets are full of red double-decker buses which are a caricature of the AEC Routemasters that used to run in London.

For Gruevski’s political opponents, Skopje 2014 consists of nationalist follies based on a confected history. Several Metabolist-era buildings disappeared under fake pediments and cornices made from G.R.C., then money became tight once again. Gruevski left office in 2017, leaving behind political turmoil, an incomplete masterplan and ballooning national debt. In his wake, urban re-development has come to a standstill. The poet T.S. Eliot believed that, “The end of all our exploring, will be to arrive where we started, and know the place for the first time.” After a week in North Macedonia, I realised I’d learned as much about Scotland as Macedonia; it transpires that Kenzō Tange’s City Gate is a Balkan Cumbernauld. The resemblance runs much deeper than the Brutalist treatment of their external elevations. The starting point for both projects was a clean sheet of paper in 1963. Just like Cumbernauld Town Centre, Tange’s City Gate consisted of a megastructure where people, public transport, service vehicles and cars were stratified, each on their own level. In both cases, only the first phase of a larger masterplan was completed – even though both were intended to become self-generating organisms which adapted to the changing needs of their citizens. Both megastructures are tolerated rather than loved by locals, and to date they’ve been saved from destruction only by political inertia and a lack of funding.

The SOS Brutalism project has flagged that both buildings are at risk, and DoCoMoMo Europe has similarly identified them as key examples of post-War development which are in danger. Although Sasho Trajkovski couldn’t have known it as we stood on the taxi rank at dawn, we shared a much deeper connection than putative tour guide and tourist. Only a handful of Metabolist megastructures was realised during the 1960’s, and two of the best examples lie unloved in small countries on opposite edges of Europe.

|

|