Sewerage: Out of Sight, Out of Mind

22 Jul 2024

New housing and the populations that go with them are overloading sewage treatment plants with an alarming frequency that demands solutions. Leslie Howson makes the case for installing localised sewage plants at every large housing development to prevent unwanted discharges into our seas and rivers.

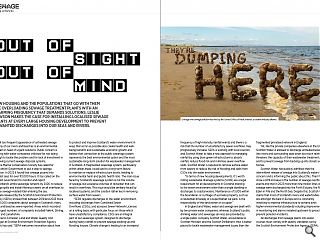

The all too frequent appearance of untreated sewage in many of our rivers and beaches is an environmental problem in need of urgent solutions. Public concern is growing with water companies criticised for not doing enough to tackle the problem and for lack of investment in improving current sewage disposal systems. The Marine Conservation Society has called for the Scottish Government to put a stop to sewage pollution. In 2022 it found that sewage poured into Scottish seas for over 113,000 hours. It has called on the Scottish Government to monitor and report on Scotland’s entire sewerage network by 2026, to reduce sewage spills and install filtering screens on all overflows to reduce sewage-related litter entering the sea. Data released by the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) showed that between 2019 and 2023 more than 2,000 complaints about sewage in Scotland’s rivers, lochs and beaches were reported. Areas which recorded the largest numbers of complaints included Falkirk, Stirling, Perth and Lanarkshire.

Sharon Forrester, Land and Water Quality Unit Manager at Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) has said: “SEPA welcomes innovation about how to protect and improve Scotland’s water environment in ways that as far as possible also create health and well-being benefits and sustainable economic growth and believe that connection to the public sewerage system represents the best environmental option and the most sustainable long-term solution for wastewater management in Scotland. A fragmented sewerage system, particularly within urban areas, could lead to a long-term failure to maintain or replace infrastructure assets, leading to environmental harm and public health risks. The main issue faced by Scotland’s sewerage system is not the volume of sewage, but excessive volumes of rainwater that can result in overflows. This issue would be similarly faced by localised systems, and the solution rather lies in removing surface water from sewers.

“SEPA regulate discharges to the water environment, including discharges from Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs), and assesses Sewer Network Licenses on a rolling basis, with particular focus on those which have unsatisfactory compliance. CSOs are an integral part of our sewerage system, designed to discharge during heavy rainfall to prevent sewage backing up and flooding houses. Climate change is leading to an increased frequency of high-intensity rainfall events and there is a risk that the number of unsatisfactory sewer overflows may progressively increase. SEPA is working with local councils and Scottish Water to take a new approach to managing rainfall by using blue-green infrastructure to absorb rainfall, reduce flood risk and minimise sewer overflow spills. Scottish Water is required to remove surface water from sewers to reduce the risk of flooding and spills from CSOs into the water environment. “In terms of new housing developments, it’s worth noting sustainable drainage systems (SUDS) are a legal requirement for all developments in Scotland draining to the water environment other than a single dwelling or discharges to coastal waters. Maintenance of SUDS within the boundaries or curtilage of a private property, such as a residential driveway or a supermarket car park, is the responsibility of the land owner or occupier.”

In England and Wales, water and sewage are dealt with by ten private water companies, whereas Scotland’s public drinking water and sewerage services are provided by a single public company Scottish Water, accountable to Scottish Ministers and the Scottish Parliament, thus is better placed to tackle wastewater management issues than the fragmented privatised network in England. Yet, like the private companies elsewhere in the UK, Scottish Water is allowed to discharge untreated sewage into rivers and surrounding seas when too much rainfall threatens the capacity of their wastewater treatment plants and to prevent sewage from backing up into streets and homes. Scottish Water has publicly admitted that the intermittent release of sewage into Scotland’s waters is a concern and is informing the public about this.

Their figures show a 30% increase in the number of sewage overflow events and that in 2023 more than nine million litres of raw sewage were discharged into the Forth Estuary, the River Eden in Fife and the North Sea. Despite this, Scottish Water claims that most of Scotland’s rivers and waterbodies are amongst the best in Europe and is constantly investing to improve infrastructure to achieve even higher environmental standards including improvements in monitoring and alarms installed upstream to proactively prevent pollution incidents. All discharges from sewage plants into water courses must comply with quality standards set by the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA). Otherwise, sewage treatment in Scotland as elsewhere in the U.K. is the responsibility of the water companies. Surface water separation and local level surface water attenuation have been a feature of Scottish sites for some time although there is room for improvement.

Local surface water management features can also provide amenity and biodiversity benefits but most importantly they can reduce pressure on the sewer network. Scottish Water collects and treats more than 945 million litres of wastewater from Scottish homes, businesses and industry every day with wastewater passing into the sewer network and one of 1800 wastewater treatment works that reduce contamination in the water to safe levels before returning the treated water to rivers and the sea. Local treatment is widely used in rural areas where there is no public sewer network and there are many relatively small local public septic tanks and wastewater treatment works in small rural communities. However, the current approach as regards waste treatment in larger urban areas is to allow hopefully successfully treated effluent to be returned to a body of water which in theory can provide a high level of dilution such as rivers or the sea. The predominant strategy as regards large new developments is to minimize the amount of surface water getting into the sewer system. However, with most drainage systems combining rainwater and wastewater along the same pipes to the water treatment works, overloading of the main sewage infrastructure is inevitable. To stop sewage backing up into homes, the stormwater and waste that would ordinarily go to Scottish Water treatment centres are released into rivers and the open sea via 3,697 Combined Sewer Overflows across the country. Unfortunately, many of these overflow pipes are close to popular beaches. Seemingly around 99% of those overflows are rainwater, surface water, road run-off, grey water, infiltration of groundwater and trade effluent. Building housing to meet the demands of an ever-growing population is a challenge in many parts of the UK especially in urban areas around towns and cities where most volume housing is currently being.

Population increases often exceed the municipal authorities’ ability to provide adequate infrastructure to deal with the new housing stock, especially in the provision of adequate sewage treatment. With the large numbers of new housing being proposed and the shortage of investment to upgrade large sewage treatment works, the current situation of polluted rivers and waters in the UK including in Scotland is only going to get worse. The extension of or development of new large-scale public sewage treatment plants often takes years to build due to budget constraints. This means that the local sewage treatment plant does not have adequate capacity to allow it to connect to new housing stock, despite an urgent need for housing. The result is that many large housing projects are being held up or prevented altogether due to the local sewage treatment plant not being able to accept any further organic load. One solution to this situation is to treat the sewage on the housing development site with a self-contained local sewage treatment plant, so that the organic load from the houses is reduced to a level comparable with the discharge standard required from the local sewage treatment plant thus enabling a development that would otherwise be postponed, or completely cancelled, to go ahead. Localised prefabricated sewage plants are available that can serve multi-house developments with a single, underground chamber purifying incoming wastewater before passing treated organic material to the main systems. The outflow into the main sewer is unpolluted water. Such systems can treat sewage to virtually any discharge standard.

The units can be located on any housing site and positioned to be most convenient for de-slugging, which is the responsibility of site management. For very large sites these could be connected to smaller clusters of houses. We Build It, an English company, can install their `flow path’ sewage treatment plant. Described as low maintenance bio treatment plants these were seemingly originally for single-house domestic projects and small rural sites but have been developed to serve housing developments of up to 125 houses of 500 residents or more if required. Support and objections to localised systems might be anticipated in equal measure from the environmental agencies, the water companies and the volume house builders. SEPA has said that the main issue facing Scotland’s sewerage system is not the volume of sewage, but excessive volumes of rainwater that can result in overflows, thus the solution lies in removing surface water from sewers. However, this does not solve the problem of raw sewage travelling from houses to our seas and rivers. SEPA has also said it welcomes innovation on protecting and improving Scotland’s water environment in ways that as far as possible also create health and well-being benefits and sustainable economic growth but believes that connection to the public sewerage system represents the best environmental option and the most sustainable long-term solution for wastewater management in Scotland.

Their concern is that encouraging localized sewage plants may result in a fragmented sewerage system, particularly within urban areas, which could lead to a long-term failure to maintain or replace infrastructure assets, leading to environmental harm and public health risks. However, the technology already exists to prevent this and whilst the logistics for installation of these localised systems will have to be worked into the infrastructure of each site the proposal is a valid alternative and one would expect it to be supported by environmentalists and the public alike. Of course, the introduction of the option to install on-site sewage treatment in large housing developments, will require new legislation and changes to building regulations are to be expected with any such approach to sewage treatment. Current technical standards guidance for Scotland applies to wastewater systems that operate essentially under gravity and provides recommendations for the design, construction and installation of drains and sewers from a building to the point of connection to a public sewer or public sewage treatment works as well as guidance on private wastewater treatment plants and septic tanks. The regulations already recognise that it may be appropriate to install a drainage system within the curtilage of a building as a separate system even when the final connection is to a combined sewer (those which carry wastewater and surface water in the same pipe) to facilitate the upgrading of the combined sewer at a later date. No limits are stipulated about the scale of such systems. Initially, housing developers might shudder at the apparent cost per house but not so much if those costs are offset by the cost of accessing the main system to be assured of planning permission. The advantages of on-site treatment of wastewater and sewage whether for single houses or a larger development are reduced infrastructure costs, reduced pressure on current sewage systems, less reliance on upgrading sewage plants and no more overloading current sewage plants giving them time to upgrade and, above all else, a significant reduction in the pollution of our waterways.

Another advantage to housebuilders is that they are less reliant on the existing local sewage infrastructure. Raw sewage in our waterways and coastal waters is a problem which must be resolved soon. Separating rainwater and wastewater in all new housing developments is one obvious way to improve the situation but, in my view, this only deals with half of the problem. Reducing the amount of rainwater runoff from buildings and surfaces will make a huge difference to the overloading of Scotland’s sewage plants. Monitoring sewage spillages is merely an early warning system, it does not solve the spillage problem. Wholesale upgrading of sewage infrastructure plants is also likely to take several years to achieve. Introducing localised sewage treatment might be an effective solution. The building of much-needed new homes to meet the government’s housing targets will only further overload the existing sewage infrastructure. At the same time, house builders are clearly under pressure with many developments delayed until the mains drainage infrastructure can be upgraded. The wider adoption of localized sewage treatment may be seen as a radical proposal but one worth considering.

There are cost implications and regulatory, technical and logistical aspects to be considered with this proposal but the introduction of more localized sewage treatment for volume housing would seem beneficial not only to the environment and current sewage systems but also to a house building industry trying to achieve the government’s house building targets. The public has a right to expect wastewater and other services to work efficiently without threatening people’s health or the health of the environment. In England and Wales, private water companies should be accountable to the public rather than their shareholders. Scotland does not have that problem as ensuring only clean water flows from local sewage treatment works is the responsibility of Scottish Water, a single nationally owned company accountable only to the public.

Of course, a modicum of responsibility lies with all of us to consider what we put down the pan, how often we flush and shower and the number of bathrooms we have in our houses. We should be more socially responsible in our use of our waste disposal systems. It should not simply be a matter of ` out of sight out of mind `. In contrast to some other countries, the UK is somewhat negligent in this regard. In Denmark for example, having a somewhat more collective-minded population, consumers tend to be more socially responsible when it comes to their use of resources. This is reflected in the approach to the design of the Solrødgård Water Treatment Plant on the island of Zealand by architects Henning Larsen which contains a recycling centre and wastewater treatment plant for the city of Hillerød, within a public park.

Described as `fit for a picnic`, the water treatment plant invites visitors to peer through skylights on the roof to watch as the plant treats 15,000 cubic meters of wastewater each day. The aim was to create a rooftop park to reduce the facility’s visual impact and invite the community to visit thus putting the public as consumers face to face with their use of resources, sparking conversation about water scarcity and climate change. Perhaps an equally innovative approach and a more responsible attitude is required in the UK, including Scotland, in the provision and design of our public sewage disposal facilities, to emphasise that only clean fully treated water should be discharged into the environment and that organic material such as from new volume housing developments be treated as close to source as possible, within the confines of the site.

Developers in Scotland are often expected to contribute to any upgrades which Scottish Water might have to carry out to the public drainage infrastructure when new developments require connection. However, whilst Scottish Water might seek to keep ahead of forthcoming development proposals, especially for new settlement or volume housing, expanding and upgrading current infrastructure accordingly, predicting such requirements may not always be possible if there are programming changes for political, financial or planning reasons. Such situations surely give strength to the argument for more on-site sewage treatment whether temporary or permanent. Either way, localising sewage treatment may offer a solution to deliver housing faster and build the numbers of homes the Scottish and UK governments are committed to delivering. Enabling developers to take responsibility for sewage treatment on their housing sites, will undoubtedly ease the challenge they, local authorities and government are facing at this time and can prevent raw sewage from ending up in our inland waterways and coastal waters.

|

|