Perth Museum: Object Lesson

22 Jul 2024

Perth Museum has placed its host city squarely on the cultural map with a surgical set piece that brings new life to an Edwardian landmark through a mix of bronze incisions and oak additions. Mark Chalmers rummages for surprises within.

Like a regenerated Doctor Who, what’s old is new again. After several years searching for a purpose, Perth City Halls has morphed into Perth Museum, which opened to the public over the Easter weekend.

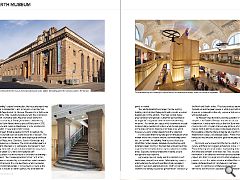

The museum serves the City of Perth plus the wider region of Perth and Kinross, and is also the new home of the Stone of Destiny. That makes this redevelopment something of national significance and international interest. Perth City Halls were originally designed by Harry Clifford and Thomas Lunan, Glasgow-based architects who put local noses out of joint by winning a design competition for the new building in 1909. Clifford & Lunan designed in a “conventional but very competent Edwardian Renaissance manner”, according to the architectural historian David Walker.

The City Halls reflect an Edwardian high point of Perth’s prosperity, powered by local businesses and benefactors including Bells, General Accident, Dewars, Pullars and Moncrieff’s Glassworks. The building was completed in 1911 and lasted almost a century in its original role. Lunan wasn’t so fortunate: he fought in the Great War, returned to Scotland suffering from shell shock and retired from practice in 1923. Apparently his health began to improve and he contemplated a comeback, but the Wall Street Crash of 1929 decimated his investments and he died the following year from a massive heart attack. By then, his building was embedded in Perth’s life and times. The Main Hall could accommodate 2000 people, the Lesser Hall around 500: they were used for concerts, ceilidhs and conferences. They also had another life, which isn’t really acknowledged in the museum displays. Perth City Halls were the Grand Ole Opry of Scottish country dance music, thanks to Bill Wilkie’s Accordion and Fiddle Festival which attracted thousands each year to listen to Jimmy Shand, Will Starr and the Alexander Brothers.

The City Halls became redundant in 2005, when BDP’s new concert hall opened at Horse Cross. The council didn’t have a plan for the old building, so it lay fallow while proposals for de-listing and demolition were quashed by Historic Scotland, then other proposals including a hotel and a food market were explored. A decade later, it was suggested that the existing Perth Museum & Arts Gallery on George Street could split in two, with art remaining where it was, while artefacts moved to a new home. The client for Perth Museum was the council’s arms-length arts organisation, Culture Perth & Kinross. As with the building’s original construction, the museum project was put out to competition – and once again a practice from outwith Tayside won. In this case, Mecanoo from Delft came third in the initial round but eventually won the commission.

Outwith The Netherlands, Mecanoo is best known for its Central Library in Birmingham which controversially replaced John Madin’s famous piece of Brutalism in 2013, the Home arts centre in Manchester of 2015, and the 2021 renovation of New York’s Public Library. Although it took a decade for Perth to realise it, the former City Halls were an astute choice for a museum. The galleried main hall fits into the same typology as the Royal Scottish Museum on Chambers Street in Edinburgh, and the Kelvingrove in Glasgow. The accommodation seems a natural fit: the main City Hall became the museum’s main gallery, the vomitory spaces transformed into slip galleries, and the Lesser City Hall is the museum’s café.

Mecanoo’s first move was to re-orientate the building’s circulation. The colonnaded entrance front to St John’s Place was superseded by an internal foyer which connects new entrances on the long elevations, which are marked by curved bronze portals. The new foyer is known as the Vennel, in allusion to Perth’s vennels, the local idiom for pends or wynds. The refurbishment shows respect for the existing building, which is listed Category B, and provides a neutral background for the exhibits. The main hall lost its pea-green emulsion and gained a buttermilk-painted interior with light-diffusing blinds stretched over the clerestory windows. It’s a bright, airy space which is generous enough to absorb large numbers of visitors, while the slip galleries to the sides compress down to an intimate scale which focusses you onto smaller objects from the collection.

It’s noticeable that money was spent in the places which matter: those which visitors see and feel when they come into contact with the building. New screens, doors and shopfitting feature cleanly-detailed oak and bronze, with polished screed flooring in the main hall, while some of the original black-and-white terrazzo was retained in circulation areas. Exposed stonework has been repaired, original fittings have been restored. Apparently one cost saving was the omission of soft landscaping around the museum. While planting trees in urban plazas is the conventional thing to do, arguably it wouldn’t have been appropriate here. Perth city centre consists of a densely-developed grid of streets bounded by the North and South Inches. The sharp contrast between the built-up and the green spaces is what gives Perth its character, compared to other city centres which are dotted with pocket parks.

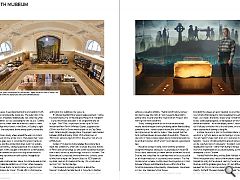

The Museum’s key attraction, and the generator of the plan, is the Stone of Destiny. In an era of cultural repatriation, it seems right and just that the Stone was returned to Perth. It’s part of a two-way traffic in artefacts: Culture Perth & Kinross returned some Maori artefacts to New Zealand, while the Stone of Destiny returned from Westminster Abbey, via Edinburgh Castle. When it was introduced into the brief, the stone gave the museum a focal point. On arrival, you’re drawn from the Vennel into the main gallery, and Mecanoo’s biggest architectural move. The Stone of Destiny is housed inside a freestanding timber Ark which sits centrally in the main hall. This is a bold intervention in an otherwise well-mannered conservation project, and it hints at insertions into other adaptive re-use projects, such as the timber vessel which Klaus Block built inside a Schinkel church at Müncheberg in Germany. Given the significance of that ancient chunk of sandstone, with its links to Alexander III, to Ian Hamilton and The Cause, it was important not to overwhelm it with infographics and security measures.

The outer skin of the Ark consists of sparely-detailed pale oak panelling, while its plain interior acts as a backdrop for the visuals. Twenty or so visitors at a time enter an anteroom, watch a series of video clips which touch on the Stone of Destiny’s eight centuries, then automatic doors swing open to reveal the Stone. Projections slowly wheel around the walls as visitors draw forward to look at the Stone. They press their noses against the glass case to scrutinise the graven marks on its top face and the grizzled iron rings sunk into sockets. They file past slowly, paying respects as if to a dead king lying in state. After a couple of minutes for contemplation, visitors are ushered back into the body of the museum. It’s a moving experience which has been thoughtfully orchestrated. A climate-controlled box above the Stone houses a small gallery for delicate exhibits on loan from other museums, and the lid over that is currently home to a giant unicorn with a lightsabre for a horn. The lid offers a 360 degree view of the museum’s main hall, demonstrating how clear and legible the building’s new layout is. It’s interesting that this museum redevelopment – unlike the renovated Burrell or the Glasgow Museum of Transport – is uncontroversial and came in on programme and on budget.

The £27mn project was funded by a £16.5mn investment from Perth & Kinross Council, supported by £10mn from the UK Government as part of the Tay Cities Deal. After a lengthy design phase, the project was realised between 2021 and Spring 2024. With a floor area of 3500sq.m. and a budget of £27mn, the works cost around £7700/sq.m. Culture PK is keen to acknowledge the community’s input into exhibitions, which aim to reflect the social history of Perth and surroundings, as well as the traditional museum fare of natural history, archaeology and local curiosities. The Stone doesn’t completely overshadow other exhibits, some of which are unique: the Carpow Boat is a 3000 year-old log boat hewn on the banks of the Tay. It’s a miraculous survivor from the Bronze Age.

The museum’s opening exhibition is about the Unicorn: Scotland’s heraldic beast, a favourite of children everywhere, and also shorthand for tech start-ups which achieve a valuation of $1bn. That blend of history, fantasy and technology also hints at how museums have had to evolve since the era when the Royal Scottish Museum and Kelvingrove were conceived. Today, creating a state-of-the-art museum usually means refurbishing an existing building, rather than building something new. Visitors expect interactive technology just as impressive as the electric brain in their pocket, but the tech can’t be allowed to overwhelm the exhibits. There are also lots of tricky cultural signals that a modern museum has to send and receive, which weren’t even factors a generation ago. Mecanoo worked in conjunction with the exhibition designers Metaphor and audio-visual production house 59 Productions, and when you enter the Ark to see the Stone of Destiny, you sense that the team has more or less succeeded on all those measures of a contemporary museum. The five minute son et lumière is subtly done: the projection is a cross between Manga and Watership Down, with hints of the forest on Dunsinane Hill evoked by Shakespeare.

Dunsinane is only a few miles away from Scone. Rather than a rousing air, or Braveheart roaring Freedom! the visuals are accompanied by an ambient soundtrack of birdsong and wind soughing through the trees. As a result, the Stone “Experience” avoids tartan kitsch, political propaganda, or falling back on Walt Disney heroes and villains. What the display doesn’t, shouldn’t, and can’t tell you is whether this is the real stone, or one of the many copies made during its long life. Just like the unicorn, part of the Stone’s allure is that it exists on a mythical level as well as having a physical outline. The Ark helps to make both sides of its existence more tangible. It’s also refreshing that this project concentrates on the core functions of a museum – to collect, curate, display and interpret – rather than trying to hang a city’s economic regeneration on a cultural building, as the V&A attempted to do in Dundee. I visited Perth first thing on May Bank Holiday Monday. While I was given a tour around the museum, a queue formed for entry to the Stone of Destiny, the café quickly filled up, and the galleries grew busy. It’s not difficult to believe that 40,000 people visited during the museum’s first month. So Perth Museum already has a popular franchise, just like The Doctor and his time-travelling phonebox.

|

|