Union Street: Long Road Ahead

7 May 2024

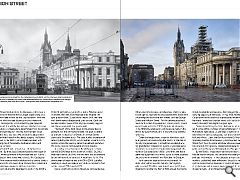

Union Street, a sore point in Aberdeen for decades, is the subject of yet another regeneration project. We piece together how the backbone of the city has evolved, as well as the steps being taken to counter the ‘death of the high street’. Is the road ahead clear? Photography by Mark Chalmers.

Union Street holds a mirror to Aberdeen, and in recent years it has reflected either a unique opportunity, or a bitter reminder of how far the city has fallen. How you interpret what you see depends on your viewpoint. It’s no longer the Union Street my grandparents knew, which Elspeth Barker portrays vividly in her novel, O Caledonia: a street where Janet “steps from the granite street and granite sky” into the warm lamplit haven of Fuller’s tea shop, visits Watt & Grant’s department store, or finds herself in the dental surgery. As Barker observed, in the 1950’s Union Street was lined with a thriving mix of hospitality, destination retail, and essential services. The Union Street I visited as a child wasn’t too different.

By then, Isaac Benzies had become House of Fraser, while Esslemont & Mackintosh was still “E&M’s”: those department stores were close to the Castlegate end. There were several bookshops in the central stretch, while Bruce Miller’s music shop, Michies the Chemist and the Capitol were nearer to Holburn Junction. When I returned to Aberdeen to work in the 2000’s, Union Street had lost some of its lustre. Retailers were in decline, then the 2008 financial crisis erupted, the spot price of Brent Crude slid far below $100, then the well-kennt names disappeared, one-by-one. Each one became another piece of the city’s personality raggled out, like an open joint in a granite wall.

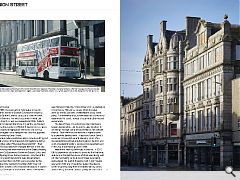

The Death of the High Street isn’t just Aberdeen’s problem, nor that of the North East, nor even Scotland as a whole. In essence, all Death of the High Street stories are the same story. The debt-fuelled expansion of retailing during the 2000’s, which pushed up rents in city centres across the country, came to an abrupt end when the 2008 crisis led to thousands of store closures. According to the Centre for Retail Research, there were 600,000 retail stores in the UK in 1950. By 2012, that had fallen to 290,000 and the trend was accelerated by our enthusiastic embrace of Amazon and its ilk. The online share of retailing was only 6% in 2006, but after reaching a Covid-era peak of over 30%, E-commerce had settled around 25% in early 2023. Some shopfronts on Union Street are still boarded up. Others are now occupied by takeaways, charity shops, estate agents, vape stores and pawnbrokers: those were once relegated to second-tier streets, such as George Street and Holburn Street. Yet the decline goes back much further than the pandemic. Union Street’s stores were threatened in the 2000’s by internet shopping, in the 1980’s by retail parks and shopping malls, in the 1960’s by supermarkets, and in the 1940’s by wartime rationing.

Other challenges were unique to Aberdeen, such as a typhoid outbreak during the 1960’s, or the loss of the city’s regional bank. I sometimes wondered why my grandfather remained so loyal to Clydesdale Bank; recently I discovered that Clydesdale merged with the North of Scotland Bank in 1950. Until then, the North Bank had supported local firms, but at a stroke, business decisions were removed from Aberdeen to Glasgow. Next came the destruction of mass transit. In 1948, Union Street was the hub of a tram system which carried 62 million people each year, yet Dobson Chapman’s Granite City Plan of 1952 argued that trams should be abandoned, because they reduced the car-carrying capacity of the roads. In May 1958, Aberdeen Corporation drove dozens of sophisticated modern tramcars – many less than ten years old – out to the Sea Beach, then set them alight in a giant pyre. Today, demolishing the Music Hall seems unthinkable, yet it came within a whisker of being flattened in 1961. Murrayfield Real Estate Co. planned to demolish it and redevelop the site as a shopping mall with a concert hall and offices. Later, the Bon Accord and St Nicholas Shopping Centres simultaneously disconnected George Street from the city centre and drew shoppers away from Union Street, then grocery shopping bled away to retail parks such as Berryden, Willowbank and Bridge of Dee. By the 1980’s, it was clear that the role Union Street had served for the past two centuries was changing, perhaps irretrievably.

In four decades, a major source of working capital had been withdrawn, the public transport system dismembered, developers tried to demolish the city’s heritage, and shoppers were siphoned off into shopping malls. Union Street hadn’t only lost retailers: it had lost its soul. In 1985, the man behind Townscape arrived in Aberdeen, when the Scottish Development Agency invited Gordon Cullen to carry out a study of Union Terrace Gardens. His initial scope was limited, but by the time the study was presented in 1986, Cullen’s brief encompassed the whole city centre. He mooted flooding the area behind Market Street to form a lagoon, he advocated bringing back the trams and turning the Castlegate into a transport hub, and he suggested pedestrianising Union Street. Gordon Cullen’s ambitious plans came to nothing, but in 1988 a group of business and civic leaders launched an initiative called “Aberdeen Beyond 2000”. Their schemes could also have changed the face of the city, by rebuilding Aberdeen Market and the Green, creating the Bravo Oil Experience Centre on Queen’s Links, and reconfiguring Union Terrace Gardens. Very few of the initiative’s recommendations were implemented. Aberdeen Beyond 2000 was succeeded by the Aberdeen City Centre Partnership’s 1991 “Heart of Aberdeen” scheme, which foundered because it couldn’t attract private sector investment. Heart of Aberdeen was followed in 1994 by “Union Street 200”, a celebration of the Granite Mile’s bi-centenary which included athletics events, concerts, street theatre, and a street party. The anniversary could have acted as a stimulus to regenerate the street; instead it became another missed opportunity. The fate of these projects proves that Aberdeen’s leaders had ambition, but lacked the determination to see things through, partly because they couldn’t secure finance. That reinforces the need for a regional bank to underwrite development.

In addition, Union Street’s economic, transportation and planning issues often descended into partisan arguments about the pro’s and con’s of pedestrianisation. Local politics repeatedly got in the way of overhauling Union Street. Meanwhile, retailing continued to decline. In 2007, E&M’s department store shut its doors for the final time, and even as the last few pieces of stock were being sold off, the marshalling yards at Guild Street were being redeveloped into a giant shopping mall. Union Square opened in 2009 and immediately pulled Aberdeen’s centre of gravity away from the traditional city centre, administering the death blow to quality retail on Union Street. To address the continuing decline, a new city centre masterplan was launched by architects BDP and the City Council in 2015. Before it properly got going on securing and spending its £280mn budget, Covid-19 broke out. That brought temporary pedestrianisation to Union Street, which proved too much for local traders, yet not enough for cycling activists. Transport planners believed that shoppers would find another way to get into the centre, using public transport, cycling or walking; instead, shoppers found a way to shop without having to go into the city centre at all.

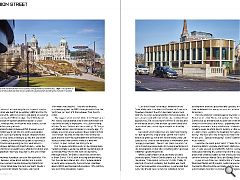

Similarly, Government policy about high streets often focuses on improving the built environment – groundscape, lighting and street furniture – yet as the Centre for Retail Research notes, while better design and redevelopment may help, they aren’t sufficient on their own. Sometimes Aberdeen can seem like a paradox. For over a decade, I wrote about architecture in a local magazine, Leopard, quickly discovering that articles about Union Street drew the most comment. Readers mostly it loved for what it had been, and reviled it for what it had become. They offered theories, acknowledging that the 1980’s brought wealth from the North Sea, yet most of it drained away from the city centre. The biggest paradox is that while Union Street’s post-War history sounds dismal, what’s been achieved in the city centre recently is impressive. The £28mn revamp of Union Terrace Gardens was conceived by LDA Design with Stallan-Brand, and completed six months ago. It’s already a success: a new walkway draws people in from Union Street, the dank arcade under the Terrace has gone, and the south-facing embankment at Rosemount Viaduct is lined with benches which are alive with children, couples, and old folk taking the air. Not far away, demolition work on the old Aberdeen Market is complete, and a new £40mn market designed by Halliday Fraser Munro will start on site shortly. Although it faces The Green, it also has a connection to Union Street. Yet it’s both revealing and disturbing that the Aberdeen Market and Union Terrace Gardens projects were proposed by Gordon Cullen, Aberdeen Beyond 2000 and the Heart of Aberdeen.

Why did they take over three decades to realise? “Our Union Street” is the latest initiative for the Granite Mile, which involves the Chamber of Commerce, Aberdeen Inspired (the city’s business improvement district), the City Council and other interested parties. It was set up to deal with a retail void rate on Union Street approaching 25%, according to the Press & Journal, and an estimated bill of £11mn to clean up Union Street and repair shopfronts, according to a report authored by Savills. Our Union Street’s objective is to take responsibility for dealing with the empty shops, graffiti and litter: it aims to brighten up the street, fill the empty units, use space better, create a central source of information, and to engage volunteers. The last two points are vital: Our Union Street is an opportunity to involve Aberdonians in the development of their city, something which previous initiatives signally failed to do. While Scotland hasn’t produced many visionary urban designers, Patrick Geddes stands out. He coined the phrase “Think Global, Act Local” in 1915. Today it’s used out of context, endlessly, but Geddes was much more than a generator of soundbites. He proposed that every city should have its own live exhibition, where development plans are presented and updated in real time: he believed that was a precondition for local democracy.

The city exhibition concept was borrowed by Terry Farrell for his Urban Room, and perhaps Our Union Street could do the same, taking over one of the empty stores on Union Street as a venue. Explaining how retailing, economics, transportation and urbanism might combine would be a first step to building on the success of Union Terrace Gardens the revamped Art Gallery nearby. The next would be to figure out how to fill the empty units. Speciality shopping? Gyms? Eateries? Music venues? Meantime, the latest public realm scheme for Union Street is a £20mn upgrade which hasn’t started on site yet. A cycle lane will extend for the full mile, but rather than pedestrianising the central stretch of the street, the project will create bus gates so that only buses and taxis can drive between Market Street and Bridge Street. A year or two from now, construction of the new Aberdeen Market and the public realm improvements to the Granite Mile should be complete – but for now, Union Street remains Aberdeen’s eternal work in progress.

|

|