Hydropower: Current Affairs

23 Jan 2024

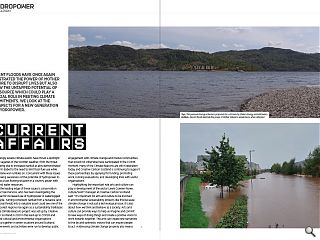

Recent floods have once again illustrated the power of mother nature to disrupt lives but also show the untapped potential of a resource which could play a crucial role in meeting climate commitments. We look at the prospects for a new generation of hydropower.

Increasingly severe climate events have thrust a spotlight on the vagaries of the Scottish weather, from the threat of flooding due to increased rainfall as ably demonstrated by Storm Babet to the need to limit fossil fuel use while the Ukraine war rumbles on. Concurrent with these issues is a growing awareness of the potential of hydropower to mediate a fast-flowing situation in a country awash with wind and water resources. At the leading edge of these issues is conservation architect Ian Parsons, who has been investigating the potential for increased use of hydropower in waterlogged Inverclyde.

Turning consistent rainfall from a nuisance (and occasional threat) into a valuable asset could see one of the UK’s poorest regions rise again as a sustainability trailblazer. The Climate Beacons project was set up by Creative Carbon Scotland in 2021 in the lead-up to COP26 and involved cultural and environmental organisations working together in seven locations around Scotland. Creative events and activities were run to develop public engagement with climate change and involve communities that would not otherwise have participated in the COP26 moment. Many of the Climate Beacons are still in operation today and Creative Carbon Scotland is continuing to support these partnerships by applying for funding, promoting work, running evaluations, and developing links with useful organisations. Highlighting the important role arts and culture can play in development of the sector Lewis Coenen-Rowe, culture/SHIFT manager at Creative Carbon Scotland said: “It’s important for arts and culture to be involved in environmental sustainability projects like this because climate change is not just a technological issue, it’s also about how we think and behave as a society. Arts and culture can provide ways to help us imagine and commit to new ways of doing things and create a positive vision to work towards together. The arts can create new narratives to live by and optimistic visions that can inspire people to act. Addressing climate change properly also means everyone should have a voice in decisions that are made and cultural organisations can play a powerful role in ensuring that everyone has opportunities to get involved and people with less power and influence are provided with a platform to share their perspectives.”

One of these projects plans to harness surplus hydro infrastructure and spare capacity in the hills above Greenock to help propel the area toward its zero carbon targets. Faced with deindustrialisation and a halving of its population since World War 2, the need for fresh water for drinking and power has reduced, freeing up a system of channels and dams for a new generation of small-scale hydro systems to capitalise on existing reservoirs around Loch Thom an area that sees average rainfall of a sodden 1,400mm per year. A far cry from large-scale hydro works in remote locations such as Ben Cruachan in the fifties, these low-key interventions won’t need to move mountains nor suffer transmission losses between source and customer, with engineering studies suggesting 1 to 1.5MW of clean electricity can be generated in this way. Aware that new pipelines snaking down the hillside as at Sloy Power Station may prove a tough sell, Parsons stresses the north-south connectivity potential of the route to punch foot and cycle paths past railways and roads to connect with Corlic Hill while mitigating floods in a high-risk zone. Extreme events are likely to place an ever-increasing burden on dam infrastructure, necessitating excess capacity in future engineering design. Despite caveats, small-scale hydro has a big role to play in delivering efficient and reliable energy, as acknowledged by a 2020 Scottish Government report which notes: ‘Small-scale hydropower has long been recognised by successive governments and energy experts as being one of the most long-term cost-effective and reliable energy technologies to be considered for providing clean electricity generation.’ That enthusiasm has translated into a new breed of pumped-storage hydroelectric power stations. For example a scheme at Loch Ness in the Highlands by Statera Energy and HRU Munro Architecture, modelled on abstracted tree branches the Powerhouse will be home to a twin turbine hall powered by discharged water from Loch Kemp.

Works to the upper reservoir will require the construction of eight dams as well as an inlet/outlet structure with underground tunnels connecting both elements. Home to a proposed visitor centre and jetty the glass, concrete and stone pumped storage complex will be positioned on the south shore at Whitebridge under a green roof and will have a capacity of 600MW - sufficient to power 156,000 homes. Turning to more modest interventions, Parsons, who is on a crusade to position Scotland as a hydro superpower by repurposing old water mills from Stanley Mills near Perth to New Lanark and Clayslaps at Kelvingrove, told Urban Realm: “The first engineering cost would be a detailed technical and legal feasibility study/design which we hope to obtain grants to pay for. When a sound business case has been put together funds could be raised by selling shares for a community interest company or similar non-profit structure. Grants would be sought for the landscape, wellbeing/ educational aspects and professional advice is available for this.” Historically Scotland built many medium-scale water power plants for industrial use, such as Stanley Mills and New Lanark with the Falls of the Clyde now supporting hydroelectric capacity.

“Possibly the world’s most comprehensive ‘Landscape of Power’ was fed by the visionary Loch Thom reservoir with the Kelly and Greenock Cuts,” states Parsons. “Up to 20 water mills and processing works formed a perfect cascade along the line of the eastern falls descending from the cut to sea level in the middle of Greenock. Unfortunately, only remnants of this enterprise remain and the art and education part of the project will be to celebrate this unique landscape and use of water power.” Has hydropower been neglected at the expense of solar, wind and wave? “Large-scale dam building has halted in rural areas since the abolition of feed-in-tariffs (payments for surplus energy). Large schemes are possible in future including pumped storage along with the “run of the river” approach, if financial incentives for long-term investment are in place. A guaranteed minimum income is needed to prepare the long-term (50-year) business case. An advantage of the kind of urban hydro that we are studying is that the transmission grid exists already. Power does not have to be transferred over long distances.” At a smaller scale circa 20 KW output the Finlaystone Family Estate, Langbank. Installed a hydro system in the 1920s - subsequently re-designed by Adrian Loening of Mor Hydro in 2022. The largest scheme currently envisaged in Inverclyde would be located in an urban area, beside a retail park, school and wastewater pumping station-giving a range of potential large-scale users, all with an interest in preventing future flooding. A critical factor is whether existing dams and underground supply pipework can be modified to connect with new hydro supply pipework and this is still to be tested. However, many community hydroelectric schemes have been built around Scotland and provide examples for us to learn from. While small-scale hydro will never be able to deliver at volume Parsons sees it as an integral part of a balanced energy mix, able to take advantage of climatic conditions when most appropriate.

Parsons said: “We expect to produce most power when there is rain and ideally mix with solar power in drought conditions. But we could be strategically important in the case of power cuts.” One innovative approach has been taken by maths lecturer turned civil engineer Penelope Carruthers who has quite literally reinvented the wheel by discarding returning to first principles to subtly improve blade curvature and inclination and so improve efficiency - vital for any micro hydro technology. Carruthers Renewables has already teamed up with the University of Strathclyde’s Advanced Forming Research Centre to make good on its promise to tackle electricity shortages in developing countries. More than just a practical solution to an age-old problem Parsons references Jean Gimple’s ‘The Medieval Machine’, a reappraisal of the technological progress made during the so-called dark ages. He observes: “Residents, investors and political scientists may be surprised to find that the world’s first capitalist company was formed circa 1250 to build a dam and mill across a river in France.

The company continued to exist until the 1960s when it was nationalised for the French power grid. Investors were awarded ‘Urshaus’ in Medieval French and the origin of the modern English word shares. Perhaps contractors and labourers were given shares for part of their work and we have the perfect model for the future of the planet?” In a world where there is nothing new under the Sun, it is perhaps appropriate that we turn full circle and revisit local solutions that don’t cost the Earth. If ever there was a time to switch the taps back on and re-energise our rural communities then surely it is now.