Mediaeval story gives sign of the future

1 Jul 2006

Malcolm Fraser undertook a thorough analysis of the history of the Netherbow before embarking on the design of the new Scottish Storytelling Centre in Edinburgh. The subsequent building is imbued with references to the past but has its own very distinctive character. By Peter Wilson

Over the years, successive planning directors have presided over a variety of approaches to renewal and infill. The results have been mixed and the street’s coherence has too frequently been compromised by mediocre interventions that pay little other than lip service to the architectural and urban context. Occasionally too, some architects have managed to secure permission to apply their own interpretation of history to modern building types, with results of questionable merit.

Since securing UNESCO World Heritage Site status, there has been a far greater obligation on the city’s planners to ensure that any new architecture introduced is not only of a higher standard, but that it complements the best characteristics of the old. This places an equal responsibility upon architects to properly understand the context within which they are working.

Since building the Scottish Poetry Library just off the Royal Mile several years ago, Malcolm Fraser has, through a succession of projects, demonstrated how a profound understanding of the history of the capital’s Old Town can inform an empathetic contemporary architecture for the area. In particular, Dance Base in the Grassmarket was a tour de force in the creation of inspiring new interiors in the hinterland of one of the city’s main public spaces, and the new Scottish Storytelling Centre at the lower end of the High Street applies some of the ideas used in that building in new and significant ways.

The location itself could not be more historically loaded – once the medieval gateway to Edinburgh, the Netherbow Port was narrowed by Act of Parliament in the 1470s to improve the city’s defences, a public gain financed by the commercial development of a series of tenements slapped across the front of existing townhouses. A shopping parade (‘luckenbooths’) at street level completed the ensemble. After the Battle of Flodden in 1513, the city wall moved eastwards, with the John Knox House reconstructed some 40 years later into the form still seen today. The Netherbow Port was rebuilt many times before being finally demolished after the Act of Union. Tenements set back from the street edge resulted from the Improvement Act, only to be replaced by the Murray Knox Church. The Netherbow Arts Centre took its place in the 1970s.

Fraser’s office has taken all of this information on board, as well as the physical form of the arts centre, and sought to use the opportunity of the new Scottish Storytelling Centre to reconstitute the notion of ‘gateway’ – not only to the city, but to “a community of artforms and cultures”. Fortuitously, the City Bell of 1621 was rediscovered during the course of the project, further justifying the stone-clad tower that has been introduced to provide formal mediation between the John Knox House and the Scottish Storytelling Centre’s new forestair. This latter element, previously used to advantage by Fraser at the Scottish Poetry Library, here signifies the relationship between thoroughfare and public entrance and visibly links the street, through the cafe area, to the ‘Storytelling Court’ within.

The Storytelling Court is the physical and metaphorical hearth of the building, a joyful, timber-lined space that is naturally illuminated through skylights and its huge picture window to the rear. The window connects the interior to the concealed garden behind, a legacy from the period when landscape architects Turnbull Jeffrey had their offices there. Cleverly, the Storytelling Centre’s rear elevation now provides a scenae frons to the outdoor ‘stage’ area around which the garden is focused. At rear ground level, Fraser and his team have sought to release the theatre space beneath the Storytelling Court from its ‘black box’ condition by providing a shuttered window to the hidden landscape.

But it is the Storytelling Court that provides the new facility with its raison d’etre: a simple but compelling space that ingeniously adapts – with its storytelling wall of boxes and niches – to provide several smaller, more intimate zones for storytelling and performance. The area, distinguished from the cafe by its increased ceiling height, can nevertheless have its audience space extended by use of the latter.

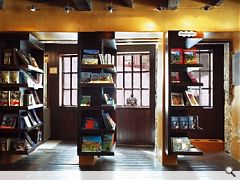

Other architectural moves have made the whole complex a richer, more useable – and more commercial – facility. The John Knox House itself has been given new life with its entrance now linked directly into the Scottish Storytelling Centre via a passageway slapped through the historic load-bearing wall. The results are striking. The house’s ground-floor area now has three functions: as entry to a historical exhibition; as a shop (within which the notion of luckenbooths has been reintroduced); and as a level access point to the newly joined facility.

Perhaps the one area that will cause ongoing debate is the building’s face to the street. The tower and the forestair have their own stories to tell and can be interpreted in many ways. Above the entrance, however, the building’s wall is plainly harled, with regular, almost domestic, windows to the rooms behind. Some may find this deliberate, understated simplicity difficult to reconcile with the public building it represents, but a look along the length of the Royal Mile suggests simplicity is not uncommon above the level of the street. It may not be ‘all singing, all dancing’ architecture, but the building’s interior more than accommodates these activities and provides the urban richness this site deserves.

Peter Wilson

The history of the site by Malcolm Fraser

This site, combining the historic ‘John Knox House’ with the adjacent Netherbow Centre, marks the historic, mediaeval gateway into Edinburgh. The original gateway’s width (see image 1) contrasted with the narrow closes which protected other entries into Edinburgh and was frequently breached by invading English armies. A commercial development in the 1470s, achieved by an Act of Parliament, improved civic defences by narrowing the approach with a new set of tenements, financed and enlivened by the high-value commercial bustle of a shopping parade which was slapped across the fronts of the existing town houses (see image 2).

After the Battle of Flodden in 1513, the city wall moved east (see image 3) to protect the new street, named the Netherbow. The reconstruction of what is now known as John Knox House was carried out by James Mossman, the royal goldsmith, around 1556, the building largely assuming its present form. The gateway was rebuilt many times, and the great bell was hung in 1621.

Following the Act of Union, the Netherbow Port was demolished as an impediment to trade, and traffic considerations caused the Victorians to build tenements back from the historic street-edge. The Murray Knox Church (see image 4) came and went to be replaced in the 1970s by the Netherbow Arts Centre, which the new Scottish Storytelling Centre builds upon – both physically and in its programme. The re-building (see image 5) uses the sense of urban compression and arrival to recover the idea of ‘gateway’ as a historic event and as metaphor and tale. The 1621 City Bell is represented in a new tower, combined with forestair entry and complementary to the Renaissance rigour of John Knox House.

The bell tower and entry look from the location of the old gate eastwards down the Royal Mile, over the new Parliament and out to Aberlady Bay. (See image 5). The bell, the gate and the place are all wound about with tales of the city and connections to it, and from it.

Read previous: Time to move from the past

Back to July 2006

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.