Artificial Intelligence: Shelf Aware

13 Jul 2023

The rapid ascent of artificial intelligence is sparking fear and awe in equal measure but what is its impact on creativity? Andy Pennington, managing director at Float Digital, asks whether architects and visualisers risk being sidelined.

AI has introduced itself in a tectonic fashion over the last couple of years. We are witnessing a new avalanche of utility and application that’s created a spectrum of debate ranging from the heatedly dismissive defence of human input to the grudging acquiescence of inevitable societal transformation. We are finding ourselves asking questions about the impact on our industries, and the effect AI might have on us as individuals. Could a process ever exist that would dramatically hasten a concept’s distillation into a designed reality? It’s an idea that, until recently, seemed so rooted in science fiction that it was at best improbable but likely impossible. Years ago, when I was introduced to ArchiCAD 5 as a sort of ‘pre-era’ BIM technology, it became immediately apparent that original and creative architectural design could exist in a parametric environment where consistent rulesets for detailing, scheduling and drawing production efficiently automated aspects of the architectural process.

In subsequent years the BIM revolution gathered speed, garnering credibility, and raising legitimate questions about how it would reshape the industry. Many at the time had lamented stories of decline and the detrimental impact on the workforce, but ultimately these proved largely unfounded as practices evolved to meet the new standard. While it seemed that we hadn’t exactly found a way of automating concept sketches to building warrants, once architects and engineers had achieved day-to-day proficiency in BIM, we might have reached what could be described as the new horizon of the modern architectural process. But realistically this was only going to prove to be the very start of the journey.

While studying architecture, I used to work in Waterstones on Princes Street in Edinburgh. One of my colleagues was a student in the Practical Application of Artificial Intelligence and in the spirit of understanding consciousness, he elevated mine that day on how much of an impact AI would have on humanity, describing some of the ways it would support our evolution as a species. ‘But it would come at a price’, he said, as he explained that one day AI would reach such an advanced level of learning, that it will know every outcome of every circumstance before we do, or even can. It’s a statement it has stayed with me to this day. But it did get me wondering how well this could truly translate to an architectural design process (or any creative process for that matter) when human creativity and originality have always been considered sacrosanct.

For example, when a 3D artist produces a concept visualisation, there is a reasonably defined process of information gathering, pre-production planning, execution, and refinement. But when these processes are broken down into sub-tasks it starts to become easier to see why AI has already had such a dramatic impact on the industry. The human creative process is inherently slow, at least by machine standards. In fact, in many ways, a slower pace is often encouraged as rushing a creative process often yields less than adequate results. For example, in the case of the ‘Unattainable Triangle’ (a discussion that is all too often revisited in design industries), the quality, speed and cost conundrum becomes dangerously unbalanced. If speed is vastly superior, and time is money, then the only remaining question is where the acceptable quality threshold lies. For many it will still be too high; detail matters and the miscommunication of intention can be costly. But in the case of concept visualisation where communicating intention is key, it’s sometimes critical to avoid committing to detail, so the quality threshold can technically be lower.

We have seen a surge in the use of AI in the concept visualisation process where accuracy isn’t required and instead, the focus is on the broad picture. But visualisation of this kind has inherent problems. The blending process isn’t flawless and upon closer inspection, you are left with a more painterly, illustrative impression of the text input. It’s common to re-feed the resulting output back into the software for continual refinement into something more robust, but it begs the question; until the technology advances further to accommodate detailed design input, is this going to cut it in terms of the quality of visualisation required? Well, the evidence suggests that it does. The question is not one of capability, it’s one of requirement. If an impression is all that’s required for a competitive bid, public consultation, or a client meeting, then an impressionist AI image will replace the traditional process for producing these.

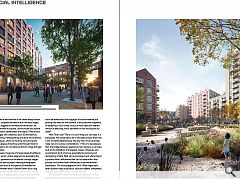

This has taken a real foothold in the urban design sector, where the scale of proposals dictates that at the early stages of the design, only suggest an architectural vernacular. Yet there’s still a requirement to explore, communicate and sell the vision at ground level to stakeholders and clients. Often artists would bridge the gap with creativity; stock 3D architecture models, photo bashing, matte painting, and other more refined, interpretive techniques, which can be time-consuming and potentially incur a degree of abortive work through trial and error with design teams. AI now allows artists to bridge that gap faster than ever before. We have also seen a huge rise of image-based AI utilities in the interior design sector, where designers are leveraging the power of AI image generation at the earliest concept stages before they even put pen to paper, creating photographic design concepts that could at first glance be mistaken for photography of a finished result.

It doesn’t seem such a big leap to imagine that with literally billions of photos to choose from, designers could collage together visuals using an almost unlimited resource of one-point perspective photography compositions, natural lighting conditions and FFE. The question could be asked about the copyright of source material, but putting that aside for the moment, is the purported originality of designing in such a way, not just a more rapid and realistic version of sketching, and a derivation of how we explore our ideas? Mark Twain said “There is no such thing as a new idea. It is impossible.

We simply take a lot of old ideas and put them into a sort of mental kaleidoscope. We give them a turn and they make new and curious combinations.”. If this is to be believed, then the bridge between requirement and delivery is a process built on the distillation of precedent, biases, influences, and environment, all of which are essentially the remixing and reimagining of data. Data can be processed, and where there’s a process there’s efficiencies that can be made within that process, and where there’s efficiencies to be made there’s automation. This is the playground of AI. What might have taken a person days to produce, could be collated, interpreted, and processed by AI in hours or even minutes.

But automation itself is nothing to be feared and in fact, should be embraced as widely as possible. Whether it’s using Adobe Firefly to hoist 3D people out from the uncanny valley with face replacement or using ChatGPT to write customized scripts with no coding expertise, visualisation studios are already employing the practical application of AI in their production pipeline. For architects, there are a whole host of technologies emerging almost daily that will revolutionise practical day-to-day working. BricsCAD BIM, for example, allows an architect to explore design alternatives within pre-constrained data inputs, while maintaining a high-level collaborative platform between consultants. Autodesk Forma, which links directly with Revit and AutoCAD, utilizes AI to simulate the implications of design decisions on sustainability outcomes. Tools to assist and guide compliance might be one of the more exciting uses of AI in the architectural process. By locking in known data and using predictive analytics to support decision-making, architects will find themselves unshackled by the disproportionate time implications of testing designs within complex regulations.

Project management and collaboration environments, where multiple disciplines and collaborators can make hitting targets challenging, will see huge benefits from cloud-based AI utilities which can mitigate resource clashes and predict missed deadlines in advance. I’ve heard it said that utilizing AI is somewhat akin to learning chess. While learning the game is straightforward, becoming a master takes years. But becoming a master isn’t necessary to win at chess, you just need to play the game better than your opponent. Are architects or visualisers going to lose their jobs because of AI? Largely speaking, the answer is no, but it’s also unrealistic to imagine a future where companies aren’t streamlined to some degree by a technology that’s gathering pace and capability almost beyond comprehension. It simply can’t be ignored, and when BIM and AI finally synergize effectively and the ripple effect in the industry will be seismic.

Those that positively embrace AI as a key component of their future will reap unquantifiable benefits from it, while those that don’t will sit on the shelf next to the conventions of yesteryear. Andy Pennington is a visualisation artist with over 20 years of experience and the founder of Float, a Glasgow-based visualisation studio that specializes in high-end, collaborative architectural 3D visualisation. Float works with clients all over the world from organisations such as AECOM and Atkins to Brewdog and Bacardi. For regular updates on new AI technologies and releases, visit www.therundown.ai/

|

|