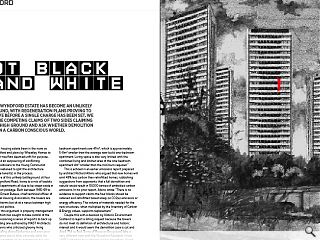

Wyndford: Not Black & White

25 Apr 2023

Maryhill’s Wyndford estate has become an unlikely battleground, with regeneration plans proving to be explosive before a single charge has been set. We unravel the competing claims of two sides claiming the moral high ground and ask whether demolition stacks up in a carbon conscious world.

Rarely has a social housing estate been in the news as much as the Wyndford and plans by Wheatley Homes to demolish 600 high-rise flats deemed unfit for purpose, which has triggered an outpouring of conflicting sentiments from politicians to the Young Communist League and has threatened to split the architecture profession (and the tenants) in the process.

At the epicentre of this unlikely battleground sit four tower blocks at Wyndford Road, home to a mix of bedsits and small one-bed apartments all due to be swept aside in a £73m regeneration package. Built between 1965-69 to designs by Harold Ernest Buteux, chief technical officer of the Scottish Special Housing Association, the towers are not without their charms but sit at a nexus between high ideals, sentiment and politics. At the heart of this argument is property management group Wheatley which has sought to take control of the narrative by commissioning a series of reports to back up their stance, including one authored by MAST Architects director Michael Jarvis who criticised gloomy living spaces from oversailing shared balconies and even poor wifi and mobile signals due to thick concrete walls.

He wrote: “The space standards of the apartments are very poor, with the bedsit apartments only 38m². The one-bedroom apartments are 47m², which is approximately 5-8m² smaller than the average new-build one-bedroom apartment. Living space is also very limited with the combined living and kitchen area of the one-bedroom apartment 4m² smaller than the minimum required.” This is echoed in an earlier emissions report prepared by architect Richard Atkins who argued that new homes will emit 48% less carbon than retrofitted homes, rubbishing suggestions from opponents that a full demolition and rebuild would result in 10,000 tonnes of embodied carbon emissions.

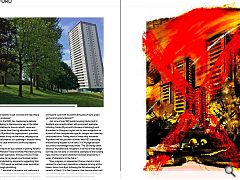

In his prior report, Atkins wrote: “There is no evidence to support claims the four blocks should be retained and retrofitted based solely on CO2(e) emissions or energy efficiency. The volume of materials needed for the new structures, when multiplied by the Inventory of Carbon & Energy values, supports replacement.” Couple this with a decision by Historic Environment Scotland to reject a listing request because the towers do not meet its definition of architectural and historic interest and it would seem the demolition case is cut and dried. Not so fast. Some of those on the ground take a very different view with the Wyndford Residents Union (WRU) standing as a lightning rod for discontent.

Asked about the redevelopment proposals the body told Urban Realm: “There have been no development proposals, not even a sketch. The drawings used in the December 2021 ‘consultation’ were generic images of houses. No architect firm has been engaged.” The consultation in question centred on a document distributed to residents which raised hackles over its use of artistic license in depicting the types of new housing residents could look forward to. Subsequent enquiries by architect Alan Dunlop, a leading opponent of the demolition bid, found that these were lifted from an alternative scheme.

Dunlop said: “In November 2021 the GHA put round a missive entitled ‘a bright new dawn for the Wyndford’ it showed drawings of very attractive houses. People on the estate therefore and reasonably assumed that the images were what the GHA planned for the estate. However, the ‘fantastic new homes’ were line-for-line tracings of a project in Cambridge by architects Proctor and Matthews. I guess traced over on the missive to avoid a breach of copyright. You can find them easily on any search engine. Just put in Housing Cambridge Proctor and Matthews. Perhaps it was thought people on the estate would not recognise the project.” Wheatley confirmed to Urban Realm that 255 homes for social rent are to be built alongside 45 at mid-market rent (starting at £435 per month), but no firm plans have been drawn up. This lack of clarity has further raised the hackles of the WRU, which added: “The reason you cannot find any definite detail is that there is none. Wheatley’s plans to blow up 600 socially rented homes that can be easily retrofitted to net zero securing social housing for the generations to come to try to cash in on the West End moving North are as threadbare as their counterfactual intellectual justification for the destruction of Harold Buteaux’ legacy.

“We have been asking for negotiation since 2021. They have refused since then to engage at all and communicate through the media at us. To be clear, we are in constant dialogue around casework issues for our members and have negotiated successfully with them before, so this pouting and infantile posturing is something they are adopting by strategy rather than just ego. It is wearing.” In an emailed statement Wheatley counters that they are ‘... still at the stage where tenants are closely involved in shaping the plans, including through the Wyndford Futures Focus Group.’ Wheatley continued: “The views of those involved with the group, which meets regularly, is an important way for tenants to get involved and help shape the regeneration proposals.” Through all this the RIAS has maintained a delicate balancing act, refusing to intervene one way or the other while stressing initiatives to discuss retrofit, reuse and demolition at a broader level. Having attended a recent public meeting in Wyndford the organisation’s president, Chris Stewart, remains firmly on the fence, refusing to be drawn on individual projects but speaking in broader terms, especially so in this case where two conflicting reports muddy the waters. Individual architects are less reticent in putting forward their views, with Malcolm Fraser and Kate Macintosh joining Dunlop in outspoken opposition.

Writing in the AJ Fraser calls for greater value to be placed on embodied carbon, noting analysis conducted by opponents suggesting that 22,465 tonnes of CO2 would be emitted under demolition versus 12,098 through retrofitting. Fraser wrote: “...we need to recognise our profession’s complicity in all this. Colleagues sometimes look askance at retrofit – ‘not proper architecture’ – for where’s the glory to be gained from humble retrofit, compared with a waste-and-spend cycle with its pontificating about style, green gizmos and good urbanism?” Just nine of over 850 public housing blocks built in Scotland are currently listed, with prominent examples including Cables Wynd and Linksview in Edinburgh and Anniesland in Glasgow, singled out for rare recognition on account of their bespoke site-specific designs and relatively untouched fabric.

Falling short of these lofty standards Wyndford will not join their number, with HES dismissing the late listing request out of hand. In a 14-page decision document, the heritage body wrote: “The 26-storey tower blocks at Wyndford are not generic in terms of their design but they are not early or innovative examples of the building type, and their original character has been lessened by a series of alterations to the fabric.” Slow progress on replacement homes stands in stark contrast to a fast-track demolition schedule to bring all the towers down from April following the full rehousing of all tenants in March. It is clear however that the arguments will not cease even after the dust has settled as the affordable housing crisis and the push toward retrofit become increasingly intertwined.

|

|