Phenomenology: Experienced Space

25 Apr 2023

Allan Murray dives into the importance of phenomenology in masterplanning, imbuing a much abused term with a sense of experience. Surfacing the human qualities which make places worth living in over the glass and steel hulks which now hold sway over too much of our urban areas. How can we rediscover the soul of the city?

Masterplanning refers to such a myriad of processes, mechanisms, and outcomes so diverse it’s hard to be clear what we mean by the word anymore. From creationist to generative, a ‘masterplan’ appears to describe and encompass fundamentally different concepts of the city. The city is inherently complex, unique and is constantly in flux, whether that pace of change is slow or fast, is one of the most interesting aspects of it. Over the centuries the concept and form of the city has been one that has intrigued not only philosophers, poets, writers, architects and artists, but also dictators, bureaucrats and those interested in power, money and control. What has always been clear is that the city evolves with society and historically reflects the structures of power within it. Given different structures of power, it’s not surprising that urban plans in the Italian city states of Florence and Rome would be fundamentally different to those of London or Edinburgh.

Equally what may have been acceptable in Haussmann’s Paris plans or indeed Craig’s New Town plan would be unlikely to be accepted today. Despite the complexities we are constantly left with the conundrum of re-interpreting our own time and our place. A reasonable question might therefore be - what is a ‘masterplan’ for a city - or even a part of the city, here, today? And given the myriad of potential outcomes what does it even mean to masterplan? To deal with the linguistic and description issue first: all urban masterplans seek to form and communicate an idea about the city, yet in many ways they are so diverse in their outcomes that it would be hard to agree that they could all be described as masterplans.

A ‘masterplan’ can be a simplistic 2-dimensional diagram, such as Edinburgh’s New Town; a very complex nexus of streets and spaces as seen in Haussmann’s Paris, or simply a redline plan area defining a zone of use. They can be written, illustrated, visionary or exceedingly technical and dull, legally binding planning guidance, community driven via local Charrette, non prescriptive or extremely specific. They are strongly influenced by who commissions them, whether they are driven by economic contingency, political expediency, legal ownerships, development finance, local social pressures – or indeed all of these at the same time! It seems to me that to move forward, we might need to step back a bit and reflect on the questions of the city itself. This is not simply a problem of definition and language; it is about how we understand the changes to our cities and our relationship with them.

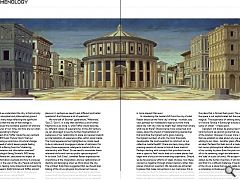

It is in fact how we understand ourselves, and the changes within the society in which we live. (When I speak of the city I am referring to a European city tradition and experience ) The city, as a locus of the means of production, population, culture and finance will always be of great interest to those seeking control and authority. In Plato’s book ‘The Republic’, he imagined that the city should reflect the very essence of who they were as a society. For Plato the ideal city is the mechanism by which an ethical and philosophical government can create a ‘happy and just’ society. The idea that the city becomes a mirror of the society that makes it, is a recurring theme throughout history and inevitably turns to philosophical matters of ethics, morals, and the spatial representations of them. It is little surprise that later philosophers and writers continued to see the city as symbolic of who we are as humans and as a corollary to how we should live. The city represented not only power and authority but also ideals of equality, justice and culture. The dramatic shift in scale of 18th and 19th century cities challenged these concepts and the city was less ideologically a place where an increasingly diverse society would be represented as just or fair.

More often, it was described as a place of great inequity, poverty, disease and yet, as we might expect, also great innovation, opportunity and progress. Novelists such as was Dickens revealed the paradox of the 19th century city - “it was the best of times, it was the worst of times”. T.S. Eliot’s “The Wasteland” (1922) described the experience of the modern city (London) as a place of enormous dislocation and fragmentation. The city was no longer a place capable of comprehension, only in part, like a puzzle. The city was now seen as less stable, capable of greater schism and also a place of great experimentation and innovation. A result of tremendous growth and economic and societal change, the city inevitable morphed into a cacophony of new shapes and forms. Throughout the stormy 20th century the city changed almost with an impatience for a new, and unknown, future. In more recent years, the so-called ‘postmodern’ city has further eroded our ‘common sense’ of the city, instead revealing its growing fragmentation, complexity, dislocation, and the increasing significance of mental wellbeing. What seems to be the important message in cantering through the ways in which we understand the city, is that not only has it shifted its conceptual and philosophical ground over centuries, in many ways reflecting the significant societal shifts, but that the rate of that change is increasing.

This raises the inevitable question of what are the critical pressures of ‘our’ time, and how are our urban environments responding to these? The futurologist Alvin Toffler made the very sentient comment in his 1970 book ‘Future Shock’ that our society is undergoing an enormous structural change, the increasing speed of which leaves people feeling disconnected and suffering from the “shattering stress and disorientation and information overload”. The German sociologist Georg Simmel’s 1903 essay ‘Metropolis and Mental life’, described the impact of overwhelming information overload and how it produces a ‘blasé’ mindset in the user of the city. People will tend to avoid interactions, feeling more impersonal and searching for spaces of escapism. Both Simmel and Toffler, almost a century apart, remind us of the effects that physical environments place on our mental health. To understand the nature of the city of our time better, and the physical impacts that we will continue to place on it, perhaps we need to ask different and better questions? And there are a lot of questions ! We now talk of ‘Boomer’ generations, ‘Millennials’, ‘Gen Z’, ‘Gen X’, in a way that identifies us and further fragments us as living in, what Toffler would describe, as different ‘waves of experiencing’.

In the 21st-century, we can also begin to see the further fragmentation of awareness of our relationship to place and spaces towards an internalisation of experience often within social media. The Covid experience has highlighted our innate need to be in nature and to engage in places of calmness. For many these experiences catalysed a mental shift in our relationship with ‘Place’. Do we need to reconsider these relational shifts and how our public spaces respond? In his book ‘Soft Cities’, Jonathan Raban expresses the importance of the imagination, and our relationships of identity and belonging when we think about the city. The architect Aldo Rossi suggested that we should stop talking of the city as physical structures but more as places of memories and feelings. Both Raban and Rossi understand the city as phenomenological; the meanings that we carry through our experience. In an increasingly fragmented world our experiences, our memory of place is more relevant than ever. In considering the mental shift from the city of what Raban would call the ‘hard city’ of things - number, size, cost, perhaps our masterplans need us to think more about the ‘soft city’ how we might ‘feel’ rather than simply what we do there? Should we be more concerned, and aware, about the impact of masterplanning approaches that prioritise the highest net to gross massing, the highest numbers of units, the most financially developable, the most expedient to construct on our collective mental health? (there are many many other pressing reasons of course to look at these metrics).

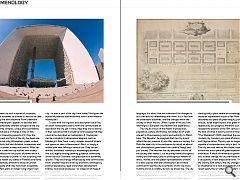

Perhaps starting with concepts that prioritise how we want a space to ‘feel’ would lead us to create places that begin with a focus on the humanising experience. Should we be focussing our efforts on ‘ideas of place’, how these connect us together through shared memory rather than places of abstract quantum. We naturally are attracted to places that make connections in our memories, this is not a plea to return to historical pastiche or to ape pattern book urbanism but to place our experience and emotional feeling of place at a higher priority. I look at places like the Piazza dell’Anfiteatro in Lucca and I ‘feel’ innately that the place that is formed feels good. The architecture of the space is not sophisticated but the overall place feels magical. The experience of walking along Victoria Street or Victoria Terrace in Edinburgh directly engages our sense of ‘street’ - it feels good.

Designers will always be pressurised to prioritise the hard facts and we cannot ignore that we play only a part of the solution. However it is even more important today that we establish an idea about why we are changing or adding to our cities - (another glass office building isn’t an idea). Perhaps this feels less of a masterplan approach but more a philosophical reflection about the relationship of our society to place. Even the post-modern novel, for all its de-centering, angst and alienation, did not abandon the ‘idea’ of a plot (of sorts). We accept that the city will always be the human invention, it will change as we do and that it is a difficult challenge. If we abandon the ‘idea’ of the city as a place that we can relate to, then we risk a completely inchoate experience of place and design spaces with less and less connection to our daily lives. If we do not recognise the importance of phenomenological experience of place on our mental health we risk abandoning the very soul of the city?

|

|