Dormant Cinemas: Not As Easy As ABC

18 Apr 2023

Sean Kinnear returns to an old haunt and explores the shuttered ABC Cinema in Kirkcaldy. A shadow of its former self the venue is indicative of the ebb and flow of cinema as a social occasion and the broader health of the communities they serve.

On the 4th of December 1969, a Pathé news reel covered Roger Moore’s arrival into the now demolished Turnhouse Airport terminal, Edinburgh (designed by Robert Matthew and completed in 1956). He was met with a welcome party of press journalists and photographers ahead of being escorted into Edinburgh’s city centre by a procession of kilted bagpipers, police constables, and senior military officers. Moore, alongside a star-studied entourage, was not there to film the latest 007 feature (his first appearance as James Bond would come four years later in Live and Let Die) but were instead special guests attending the grand opening of Edinburgh’s shiny new £350,000 (or roughly £5.6m in today’s money) ABC cinema at 120 Lothian Road.

At the time, not only was this both Edinburgh and Scotland’s most luxurious and technologically advanced cinema, but the new ABC Film Centre as it was named, was actually Britain’s first ‘multiplex’. Considerably modest by today’s standard the cinema had the capacity of seating audiences of nearly 2000 across three separate screens - simultaneously showing three different movie titles - entirely unprecedented for even the late-1960s. Amongst the famous actors and film industry bosses, all smartly dressed in fine evening attire, was Willie Ross, the then Secretary of State for Scotland (a precursor of sorts to Scotland’s First Minister). As Willie Ross conducted the ceremonial ribbon cutting the black and white Pathé news reel boldly announced how his presence ‘indicated the important role of the new cinema in the nation’s social life.’

Additional scenes from the short two-minute news archival clip shows bartenders serving flutes of champagne and as the mustering crowd fill the foyer spaces the reporter describes the ABC Film Centre a ‘necessary part of Edinburgh’s thriving scene.’ Despite this promising outlook the one-time cultural and social asset has all but been demolished. While a modern four-screen ‘miniplex’ Odeon cinema has been remodelled in the basement, the building’s grand auditorium was removed in 2000 as the building subsequently became used as commercial offices. Category B listed building status has secured the retention of the ABC’s original stone façade, but the cinema’s fine Art Deco interiors can only be gleaned through websites like Scottishcinemas.org (a vast database ‘dedicated to the recording and archiving of Scotland’s historic cinema architectural heritage’).

Established by the Scottish solicitor, John Maxwell, in 1927, the ABC (or Associated British Cinemas) chain is synonymous with 20th century cinema history. Urban Realm’s ‘Save the ABC’ story, published in April 2019, featured archival images of the old ABC in Glasgow where queuing crowds lined Sauchiehall Street; a typical scene in the halcyon days of cinemagoing, yet a sight rarely matched in modern Scottish society. Although the ABC cinema chain principally operated from the 1930s through the 1980s the name continued to appear well into the 2000s before a corporate merger eventually saw the Odeon brand as the chosen successor.

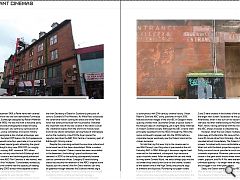

I’m told that my first ever trip to the cinema was to see Walt Disney’s Lion King when it premiered at the old Kirkcaldy ABC in 1994. Although it became a regular treat reserved for the weekend, subsequent trips became a quasi-ritualistic event. After we parked the car and made our way down Oswald Wynd, we would always pop into the old sweet shop directly next door to the cinema, located at the eastern end of the High Street, and procure bags of bonbons and liquorice. Purchasing our paper tickets from the pokey box office installed at the main entrance, I always remember seeing exiting audiences funnel down the opposite staircase (screened in a sort of glazed partition system) and out into the street. Inside, the smaller screens 2 and 3 were located in the bowels of the building with the larger main screen 1 accessed via the upper levels. Afterwards, when it was our turn to descend the exit staircase we often walked along to McDonald’s for a ‘Happy Meal’; which, having partnered with the movies showing at the ABC, always included a collectible toy. However, when the new Odeon multiplex opened 15 miles away at Dunfermline Fife Leisure Park in 2000 – a mere 20-minute drive from Kirkcaldy –the death knell sounded almost immediately.

The Odeon’s ten (larger) screens, furnished with more comfortable seating, and kitted out with the latest projection equipment and Dolby surround sound provided a much more immersive cinematic experience. Moreover, patrons were spoiled for choice in the giant snack kiosks where hotdogs, nachos, ice-cream, popcorn, and Pic N Mix were available in seemingly unlimited quantity – no longer were we required to stock up and smuggle in our third-party treats. Sadly, the Odeon-owned Kirkcaldy ABC didn’t last long after its newer and bigger Dunfermline cousin appeared. The Category B listed cinema soon fell out of favour and when the company decided to focus efforts on the new Dunfermline venue Kirkcaldy ultimately ceased operations around the end of 2000. By 2004, after lying vacant and neglected, the old cinema swiftly fell into a state of disrepair and was added to Scotland’s Buildings at Risk Register. Although subsequent reuse attempts fell through, in 2016 the ‘King’s Theatre Trust’ entered stage as a serious contender committed to reviving the treasured piece of Fife’s cultural and social heritage.

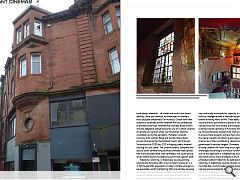

The ambitious proposals include reinstating the original single-space auditorium (as it was during its time as the King’s Theatre) as a dynamic performing arts venue. The 3D visualisations published on the project’s social media streams hint towards the fantastic potential of this refurbishment, one which could enact a catalyst opportunity to revitalise the broader community through a vibrant and inviting social space. The Trust, along with the help of local volunteers, set to clearing the decayed and collapsed building fabric and funding from Historic Environment Scotland facilitated emergency roof repairs to make the building wind and watertight again. Progress photographs of the on-site works richly capture paint-peeling walls, debris piles, and leftover cinema equipment that evoke images often found through urban exploring forums.

Crucially, during the removal of a suspended roof as part of the foyer clear-up magnificent plasterwork ceiling details and stained-glass windows were revealed; the Art Deco elements being the remnant features leftover for the original King’s Theatre completed in 1904. Likewise, in lifting the old red cinema carpets part of the original Italian Terrazzo floor and marble stair steps were unearthed. Listed building consent was approved by Fife Council last year to allow the erection of temporary site works to protect and enable safe access into this historic foyer. However, progress with the longer-term project aims seems to have slowed for the time being. In a recent interview with the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg, the Oscar winning director, Sir Sam Mendes, whose latest works include the visually stunning Skyfall and 1917 suggests that the act of physically going to the cinema is becoming a dying social practice. In a pointed critique towards the growing prominence of home-streaming-on-demand services Mendes recognises the industry needs that are required to draw crowds back through the cinema doors. Here, he highlights the importance of movies being consciously made for the big screen and by doing so, will help recreate that unrivalled experience of visiting the cinema as an ‘event.’

Admittedly, my own practice of going to the movies entered a form of hiatus even before the existential COVID-19 threats prohibited such acts. And when the national lockdown was officially announced three years ago this month, like others, I turned to sampling the novelty of watching new cinema releases at home. Although the viewing cost matched the price of a cinema ticket, I had to settle for watching these fresh titles on a standard-sized iPad – nowhere near the same as the big screen immersive experience they were intended for, but it was a measurable way of supporting the arts in difficult times. Post-lockdown I rediscovered my love of cinemagoing by a chance circumstance. A friend, who shall remain anonymous (solely for the reason a glitch in their Cineworld Pass credited an extra ticket with any purchase) kindly gifted me a free pass on Wednesday’s and we went weekly in late afternoons or early evening before work. While this is undoubtedly still an expensive social activity, when enjoyed occasionally, few would disagree that watching movies in theatres overwhelmingly trumps the at-home experience.

Incidentally, some independent venues, like the New Picture House in St. Andrews or the Grosvenor Cinema in Glasgow have been ahead of the curve well before home-streaming-on-demand threatened vital cinema footfall. By offering novelties such as living room-type sofa seating and table service these settings have orientated towards assimilating home comforts; where cinemagoers can enjoy the benefits of the social outing, the big screen, and immersive experiences, whilst also retaining a more familiar atmosphere. Pivotally, these unique selling points seem to have ensured a continued appeal to film fans and thus survival for these smaller, non-chain cinemas whilst the larger ABC complexes – historically more dependent on mass crowds – struggled to adapt with changing consumer patterns. Inflexible building programmes, anchored to this outmoded model, have undoubtably contributed to instances of gradual decline, closure, decay, and eventual demolition of Scotland’s ‘golden age’ cinemas. Historically, the cinema as an architectural typology has evolved markedly over the last 100 years; ranging from luxurious theatres of the early 1900s (including Lothian Road and Kirkcaldy ABCs) to state of the art, 21st century leisure complexes like Dunfermline Odeon. However, its basic design elements - of screen and auditorium tiered seating - have and continue to showcase the cinema’s multi-purpose credentials.

For instance, Odeon now offer screens to corporate events whether that be conferences or private screenings. Alternatively, perhaps lesser known was the adaptable (albeit temporal) use of Scottish cinemas as remote jury centres when court buildings became unsuitable during the pandemic. Multiplex cinemas, including both Lothian Road and Dunfermline Odeon proved vital assets for the Scottish Courts and Tribunal Services across 2020 and 2021 in helping clear a bloated backlog of court cases. The cinema screens, complete with secure video-conferencing facilities provided ideal spaces that were soundproofed, well-ventilated, and could ensure social distancing for the attending jurors and support staff.

Retaining, restoring, or adaptively reusing existing cinemas like Kirkcaldy ABC is by no means as easy as 1, 2, 3. Yet the benefits, especially in today’s climate emergency, are especially worth highlighting. Not only do they assuage our collective appetite for investigating social histories and conjure nostalgic memories, but these remnants of our built heritage can and should be seen as vital community assets. Much like its 20th century ancestors, the cinema has continually showcased its capacity to survive drastic industry changes aimed at maintaining pace with the forever evolving world of film. Their ability to adapt for reuse (either as performance spaces or conferencing venues) must be more widely acknowledged. And ongoing schemes like the retooling of Kirkcaldy ABC can and should be more proactively assisted with vital government support to ensure these projects achieve their aims.

Furthermore, the clearer benefits of retaining and repurposing old cinemas lie in their contributing values towards the government’s net-zero targets. Ultimately, while reviving existing cinemas will most likely incur significant financial challenges (according to individual conditions) the overall cost of this approach is comparatively less than demolition and construction anew (alongside a much more reduced embodied carbon footprint). As detailed above, retaining, restoring, or adaptively reusing cinemas can be tailored to more flexible, much broader building programmes than not only ensure longevity but successful outcomes can reactivate a stagnant high street and act as a catalyst for future community redevelopment. So, here’s hoping the old Kirkcaldy ABC answers its encore and will welcome in the crowds once again.

|

|