Islay Distilleries: Whisky Galore

17 Apr 2023

Mark Chalmers explores the roots of a whisky renaissance on Islay, sampling Caol lla, Ardnahoe, Ardbeg and Port Ellen along the way. How is the architecture of modern distilleries shaking off ‘pagoda’ cliches? Photography by Mark Chalmers.

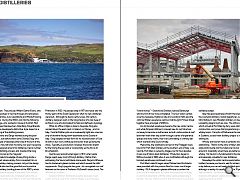

While lines of cars wait to board MV Finlaggan at Kennacraig, two low-loaders nose onto the ferry’s bow ramp. Each carries a giant stainless steel vessel which looks rather like part of a space rocket. The cargo causes much speculation among Islay’s visitors, who creep forwards in their VW T4 vans, touring bikes and SUV’s.

Islay was shrouded in mist that morning. Our first sighting was of its shore, shelving away to the Sound: turquoise-grey water fringed with foam and a rim of peat brown. The island is large enough to have its own identity, and its ferries, like Finlaggan, are ocean-going ships. Crossing the Sound feels like travelling to a kingdom across the sea.

Yet Islay is also small enough to be a microcosm of Scotland, its economy powered by agriculture, seafood, tourism – and whisky distilling. So local folk knew, of course, that Cadzow Haulage’s lorries each carried half of a washback, part of the alchemical plumbing which transforms grain into spirit.

The Scotch industry moves in cycles. Over the past three centuries, it’s gone from extravagant booms, which result in a glut of spirit, to deep busts, which see distilleries mothballed for a decade or more. After thin times at the end of the 20th century, the current exuberance has sparked a distillery boom the likes of which happens only once every couple of generations.

The new developments range from micro-distilleries dotted around the country, often well beyond traditional whisky areas like Speyside, to new mega-distilleries at Dalmunach and Macallan. However, the boom’s effect is particularly marked on Islay – the Hebridean island whose culture and economy are intoxicated by malt whisky.

The architects who shaped distilling aren’t well known, even within our profession. They include William Delmé-Evans, who was the post-War pioneer of new techniques and processes; he designed Tullibardine, Jura, Glenallachie and Macduff during the 1950’s and 60’s. During the 1960’s and into the following decade, Leslie Darge, who worked in-house at Scottish Malt Distillers, redeveloped Glentauchers, Aberfeldy, Royal Brackla and Caol Ila. He too developed a distinctive style, based on a deep understanding of the distilling process.

Both Delmé-Evans and Darge worked during the post-War whisky boom, but before them came Charles Doig, who practiced for a couple of decades either side of the turn of the 20th century. You may not know his name, but you’ll recognise Doig’s work. He designed around 50 distilleries, held a number of patents for the distilling process, and invented the Doig Ventilator – better known as the “pagoda”.

Doig had a detailed knowledge of everything inside a distillery, to the point where whisky firms consulted him on all aspects of the whisky-making process, not just the design of the buildings. He also had the good fortune to practice during the great distillery-building boom of the 1890’s, which preceded the calamitous decades of the early 20th century.

Charles Doig’s best work was completed before the so-called Pattison Crash of the early 1900’s, which was followed by swingeing tax rises in 1909, then the Great War, and US-wide Prohibition in 1920. He passed away in 1917 and never saw the thirsty years of the Great Depression when no new distilleries were built. Although he died a century ago, 21st century distillery designers work in the long shadow of a rare type of architect: one who dominated his field and defined a typology.

While his office in Elgin is close to Speyside, Doig also worked down the east coast, in Ireland, on Orkney – and on Islay. Caol Ila Distillery sits on an awkwardly tight site, a narrow strip of shoreline facing north-eastwards to the Sound of Islay. Doig adopted a linear form for his reconstruction of Caol Ila with its tun room, stillhouse and bonds lined up along the shore. Typically, as production increases the bonds stretch further along the sea wall, or occasionally up the hill, as at Bruichladdich.

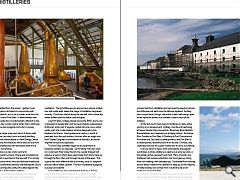

Caol Ila was reconstructed again in 1972, when Leslie Darge swept away most of Doig’s distillery. Rather than addressing the Sound with blank stone walls, Darge’s stillhouse has his trademark glazed curtain wall which reveals the stills’ copperwork. Doig’s pagoda has gone – its corrugated iron roof featured on the cover of Professor McDowall’s classic book, The Whiskies of Scotland.

Simpson & Brown Architects recently designed a new visitor centre at Caol Ila for Johnnie Walker, one of Diageo’s global whisky brands. In fact, Caol Ila is one of Johnnie Walker’s “brand homes” – Glenkinchie Distillery outside Edinburgh was the first of four to be completed. The four visitor centres covering Speyside, Highland, Islay and Lowland malts plus the Johnnie Walker experience centre in Edinburgh’s Princes Street together have a budget of £185mn.

An old bonded warehouse became the new visitor centre, and while Simpson & Brown’s concept saw its roof structure cut away to become a roof terrace, as built, visitors enter at roof level then work their way down through a series of experience spaces and story rooms, their visit culminating in a whisky bar which overlooks the Sound of Islay.

Meanwhile, the washbacks carried on the Finlaggan were bound for Port Ellen Distillery, at the southern end of Islay. Like Caol Ila, Port Ellen is owned by Diageo, but for four decades it was one of Islay’s silent distilleries. Production began in 1825 and ended in 1983 when it was mothballed, although the bonded warehouses continued in use.

Port Ellen’s rebirth began when Michael Laird Architects were provided with the process flow for a new, much larger distillery. MLA designed a glazed stillhouse to contain the stills, tuns and washbacks: as I write, the production building is wind and watertight, with the visitor centre progressing in parallel. The new stillhouse forms the third side of a courtyard – which acknowledges a traditional court typology which many distilleries adopt.

Islay has good examples of both the linear distillery and the courtyard distillery; radical departures, such as Rogers Stirk Harbour’s new Macallan Distillery on Speyside with its undulating diagrid roof, are rare. The stills and washbacks which arrived at Port Ellen by ferry were slotted in during construction, and prove that programming is key during a whisky boom. Forsyths of Rothes are the sole supplier of stills in Scotland, so each new distillery project is added to their waiting list.

Whisky and tourism have a symbiotic love-hate relationship. Thanks to the draw of Islay’s distilleries, the island’s restaurants bustle and the hotels are full, but locals don’t stick around in hospitality when there are better-paying jobs in whisky. Yet tourism is fundamental to the island’s economy, and especially valuable for new distilleries.

Nowadays the visitor centre opens before the malt is bottled, because you have to wait for at least three years and a day before you can sell newly-distilled spirit as “whisky” – although in reality it’s usually an eight or 10 year wait for single malt to mature. So malt whisky is a business for long term investors with patient capital, and meantime tourists help to keep the enterprise afloat.

Ardnahoe is one of Islay’s 21st century distilleries, with a visitor centre integrated from the outset. I gather it was designed by Iain Hepburn Architects in conjunction with Campbell Morris Architects, and is on a smaller scale than the Diageo sites at Caol Ila and Port Ellen. It demonstrates how the programme of newbuilds is fundamentally different to the historic distilleries: it has a visitor centre rather than a stillhouse at its heart. Ardnahoe has a pagoda roof which is purely symbolic.

At the end of the single-track road which it shares with Caol Ila and Ardnahoe, lies Islay’s most northerly distillery, Bunnahabhain. On the hillside above is a new Energy Centre designed by Threesixty Architecture, which takes its cue from traditional bonded warehouses with blackened walls and a rhythm of repetitive roof pitches.

On the shore below is a new visitor centre for Bunnahabhain, designed by Avison Young and completed at the end of 2019, which is perched on the sea wall. It’s a simple black timber-clad volume which hints at traditional boathouse architecture, with a cantilevered balcony overlooking the Sound of Islay. Both new buildings are subtly articulated against the whitewashed masonry of the historic distillery.

At the southern tip of the island, Ardbeg was rebuilt by Charles Doig around a much older core. It’s become the archetypal island distillery, with whitewashed rubble walls, a cluster of slate roofs and a pair of steep pyramidal Doig ventilators. The old stillhouse is an anonymous volume, a black box with white walls where the magic of distillation happened covertly. The bonds stretch along the sea wall, with a stone slip where puffers used to deliver coal and grain.

Like Port Ellen, Ardbeg closed during the 1980’s slump, but it reopened a decade later and has been steadily redeveloped. Ardmore’s iconic pair of pagoda-roofed kilns are now a visitor centre, part of a modernisation scheme designed by Iain Hepburn Architects. Having cleaned a century’s worth of peat reek from the roof timbers, the kilns offer an insight into how Charles Doig was a combination of architect, structural engineer and process specialist.

The first Doig Ventilator began as an experiment at Dailuaine distillery on Speyside. Germinating malt was dried on a wire mesh floor inside the kiln: the cupola-shaped roof acted as a venturi which drew peat smoke from the furnace up through the floor, then out through louvres at the apex. The cupola was more effective than a chimney, since it’s rainproof and provides a better updraft. The fact it resembles a pagoda is purely coincidental.

A new stillhouse was completed at Ardbeg in 2021 by French practice INCA Architects, working for its current owners, the multinational luxury goods company LVMH. Like Port Ellen and many others, the stillhouse incorporates a Darge-inspired glazed curtain wall. The glazing helps to dissipate process heat from distillation and removes the need to remove the stillhouse roof each time the stills are replaced. Ardbeg has a unique twist, though: the entire curtain wall swings open under hydraulic power, as a dramatic coda to tours of the distillery.

At the last count, there were 12 distilleries on Islay, either working or in development. Ardbeg, Caol Ila and Laphroaig all have a Charles Doig connection. Bowmore, Bruichladdich, Bunnahabhain and Lagavulin are similarly historic. Ardnahoe, Elixir Distillers at Port Ellen, Ili Distillery at Port Charlotte and Kilchoman are 21st century developments; and Port Ellen is a contemporary reconstruction of an old site. Of those, only Laphroaig still uses its cupola-roofed kilns to carry out malting.

In an era which is heavy with iconography, the pagoda symbolises a whisky distillery as clearly as a spire says kirk, or the golden arches represent junk food. Many Victorian-era distilleries had cupola-roofed kilns, but most gave up doing their own malting a few decades ago. Traditional floor maltings are too labour-intensive for distillers to keep up, so the majority of malted barley now comes from industrial-scale drum maltings such as Port Ellen.

So Doig’s Ventilator has become a post-modern symbol, rather like Robert Venturi’s duck. Folk recognise it intuitively, and that is Charles Doig’s immortal gift to Scottish architecture. It’s a pity that he didn’t trademark it.

|

|