People Make Places: Places & Spaces

23 Jan 2023

The placemaking agenda has been driven up the political agenda by recent events, throwing up novel ways of managing urban environments. We look at the work of Glasgow’s Place Commission to see what forms the post-Covid city could take and how this might influence our relationship to home.

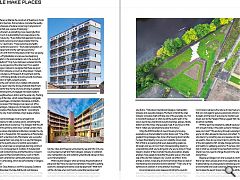

News that Glasgow City Council is scrutinising new ways to create and manage public spaces to support the economy, health and social programmes raise broader issues around how our urban environments should evolve in response to the climate emergency. Here we examine the placemaking agenda: is it an example of democracy in action or a financial necessity? Prepared by the Place Commission for Glasgow, a specialist group chaired by City Urbanist professor Brian Evans, People Make Places calls for the transfer of assets to communities in a process modelled on the housing stock transfers of the last decade.

As a means to kickstart physical and social regeneration at a neighbourhood level, the process is billed as a Place Stock Transfer which would see ‘stranded’ property, land and public goods transferred on a neighbourhood level where the local authority lacks resources to undertake essential maintenance. Mentioned no fewer than 842 times in the 200-page document the word place implies an emphasis on the micro-geography of our everyday lives that have assumed heightened importance in recent years, but how do the report’s authors define the term?

Lead author Evans told Urban Realm: “Place is a little bit like beauty, we know what we mean but to a greater or lesser extent it is in the eyes of the beholder. You can design according to a series of well-known principles such as position, proportion, materiality, colour, and texture. You can use accepted rules and what you can come up with can be good, bad or indifferent and in some cases beautiful but I don’t think you can start by saying I want to design something beautiful. When you follow these rules, you can come up with something beautiful, like Corbusier’s Villa Savoye. But a lot of people will say ‘that’s ugly’.

“We use the word place as a noun and as an adjective, it’s a bit like urban. Place is a little like the construct of Dualchas in Scots Gaelic or Heimat in German, that somehow connotes the quality, value and attractiveness of a place concerning its physical and cultural features that give a sense of belonging.” Positioning the term as something more meaningful than a blandishment such as sustainability Evans sees place as the lynchpin of the future city. “If you follow that approach to place, it takes you towards outcomes and values broader than the purely monetary”, says Evans.

“These outcomes are health, social, environmental and economic - the fundamental pillars of sustainable development and the well-being economy.” Is this part of a shift from thinking big to small? Are we seeing the shine come off globalisation and are we now beginning to reassess localism in the post-pandemic era in the pursuit of homegrown solutions? “Only if you had been suckered into the position that one was good and the other bad. It’s an explicit attempt as Glasgow matures to recognise that there are good things to learn from Glasgow as much as other places.”

Instead, Evans points to studies by UK Research & Investment and the UN proposition of thinking globally and acting locally to achieve quantifiable goals in a highly subjective arena. The road to the post-carbon city is riddled with potential potholes but the report cites the strong emotional attachment Glaswegians hold for their home city to be among its greatest assets, with a standing army of engaged individuals ready to fight for their neighbourhood, district and the wider city. Pointing to an EU quality of life index, which ranked Glasgow, alongside Manchester, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, Barcelona and Berlin, Evans said: “I discovered That Glasgow was never out of the top three. Copenhagen, Glasgow and Amsterdam consistently outperform Barcelona, Manchester and Berlin - according to the citizens of the city. It demonstrates a high degree of place attachment.”

These inherent advantages must be set against an overarching tendency to talk ourselves down, something that Evans is evangelical about countering: “The Glasgow that the UN uses is based on the primary urban area. Outside London, there are five UK cities where international institutions consider the city to be larger than it is. People think 1.5m people live in Manchester, it’s 520k. I couldn’t understand why Manchester was successful in convincing people that it was a big city in a way that Glasgow does not. I think this is partly down to Scottish parochialism.

“The primary urban area is a recognised planning construct in England but it is not recognised in Scotland. It includes East Renfrewshire, East Dunbartonshire and Renfrewshire. It doesn’t include Inverclyde and West Dunbartonshire, South or North Lanarkshire. South Lanarkshire is particularly bizarre because Rutherglen and Cambuslang, which are self-evidently in Glasgow, are not included.” “The Scottish Cities Alliance is not fit for purpose; Scotland has four cities. Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow because only those cities elect an authority to run the city. Unlike Stirling, Inverness, Perth and god help us, Dunfermline, Scotland has four cities and three are surrounded by sea and hills. Only one is surrounded by itself and that’s Glasgow. Glasgow is Scotland’s only metropolitan city and Scotland systematically refuses to face up to that proposition.”

What would a Glasgow which embraces the prioritisation of place look like? Have we been too beholden in the past to putting economic development before social development? What form will the city take when community ownership becomes real? “We have become too beholden to the neo-liberal hegemony but I don’t find that constructive, it creates binary arguments,” says Evans. “I talk about international Glasgow, metropolitan Glasgow and everyday Glasgow. My thesis is that all the cities Glasgow compares itself with take care of the everyday city. This is important because it is what we call the public realm in the way it used to be understood as public buildings, spaces, railway stations and the milieu where people meet. If you focus on that then it makes your job elsewhere easier to achieve.” Citing the 2003 transfer of council housing to housing associations as the template for action Evans said: “One of the greatest things Glasgow has done is the housing stock transfer. I’ve been fascinated by how you turn a liability into an asset. Part of that is recognising that even depreciating assets are still assets and you can turn them into appreciating assets by understanding what you’re doing and why you’re doing it. Fraser Stewart, director of New Gorbals Housing Association, already employs more people to look after the public space in the south side of the city than Glasgow City Council can afford.”

Is this entropy in action, where any environment where there is a lack of maintenance and care tends towards disorder? “That’s one of my definitions of urbanism. It is the antonym to entropy.” An accompanying press release promoting the council’s embrace of these ideas made mention of the City Administration Committee ‘requiring’ council officers to work with the Place Commission, betraying the nature of a top-heavy bureaucracy that can work against genuine grassroots activism. Dwindling budgets and the lack of resources to maintain even crown jewel assets such as the People’s Palace suggest that major changes are all but inevitable. Will the report be adopted by default because there simply isn’t enough money in the public purse to manage spaces as they were pre-Covid? “We are living through a paradigm shift, and you’re not often allowed to step back and reflect. You have people who like to try something new and people who like to do things as we used to. How do we come to terms with the interrelationship of the demographic shift, climate change, technological progress and health in a wellbeing economy? If we have changed the dial on what we consider to be important and how these things interact we may need to change the dial in the way we go about doing things.”

Bigging up Glasgow can only succeed as a bottom-up rather than a top-down process and a more systematic approach to placemaking is a prerequisite to addressing economic, environmental and social outcomes. By showing that everything has its place the report shows how intangible attributes such as civic pride can go a long way towards tackling the big challenges of our time, from climate to the economy and social justice.