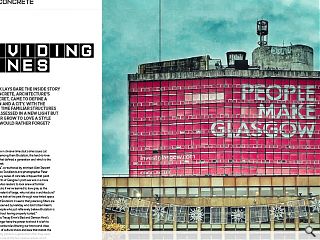

Braw Concrete: Dividing Lines

23 Jan 2023

A new book lays bare the inside story of how concrete, architecture’s dirtiest secret, came to define a generation and a city. With the passage of time familiar structures are being assessed in a new light but can we ever grow to love a style that many would rather forget?

It’s often said we live in divisive times but some issues cut deeper than most, among them Brutalism, the hard-to-love architectural style that defined a generation and which is the subject of a new book.

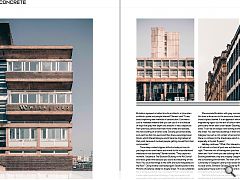

“Braw Concrete”, co-authored by architect Alan Stewart of Lifschutz Davidson Sandilands and photographer Peter Halliday, is a sprauncy series of concrete critiques that paint misunderstood giants of Glasgow’s post-war era in a more flattering light. It invites readers to look anew at familiar surroundings and asks if we’ve learned to love grey as the interior design equivalent of beige, why not also in architecture? It’s often said we look at the past through rose-tinted specs but when looking at Brutalism it seems that polarising filters are in vogue, a point observed by Halliday who told Urban Realm: “There are some people who just reflexively believe Brutalism is dowdy or dingy without having properly looked.”

In a world where Tracey Emin’s Bed and Damien Hirst’s Pickled Shark no longer have the power to shock it is left to the many concrete carbuncles littering our towns and cities to represent a form of cultural shock and awe that stands the test of time, inflaming passions a generation after they were built. Architecture is one of the few creative arenas which can still elicit visceral reactions from the broader public. Does Brutalism represent a better time for architects, a time when architects spoke and people listened? Stewart said: “It was about exploring new methods of construction.

Concrete is such a malleable material that you can cast it in a multitude of ways that play with depth and shadow. It was a departure from previous periods that were more ornate and delicate, this was building on a heroic scale. Society got carried away and went too fast, too quick and then there were large tower blocks which littered Glasgow and it became stigmatised at that point because it involved people getting moved from their communities.” These deep-rooted stigmas still echo today so how do you begin to win over hearts and minds to the misunderstood treasures on our doorstep? Stewart added: “They capture a moment. I studied at The Bourbon Building in the Art School and had a great time because you could do everything on the floor. You could nail things to the soffit and build maquettes on the floor.”

Citing another overlooked gem Stewart points to the Ministry of Defence citadel on Argyle Street. “It is very utilitarian but it serves a purpose. Yes, it is closed off but I very rarely see a wide-open government building. It may be onerous to its surroundings but when you walk around it you find merits in its nature.” We associate Brutalism with grey concrete boxes but this does a disservice to the enormous diversity under the broad stylistic blanket. It is an approach which benefits from engineering rigour but the lack of colour makes it hard to love, particularly when seen under leaden Glaswegian skies.

Stewart adds: “It can be an oblique view looking at these buildings from the street. You see these buildings in their broader context. Glasgow has such a rich context of red and blonde sandstone, there is a richness to the streetscape which is always changing, especially in the last 15 years.” Halliday continues: “What I find interesting about Glasgow is it’s almost a school of post-war architecture in its own right. There are a lot of homegrown practices with local talent and I don’t think you see buildings like the Bourdon Building elsewhere, they are uniquely Glasgow and nod to the surrounding environment.

The work of William Whitfield (University of Glasgow Library) was career-defining. It’s among his best works. Elmbank Gardens Tower by Richard Seifert isn’t quite Space House but it’s not far off it and as good as anything his practice did outside London.” We think of the post-war era as the birth of internationalism and the death of localism but its reputation for incongruent towers plonked down haphazardly in our cityscapes isn’t wholly deserved, with the style lending itself to be richly contextual in the right circumstances, as Stewart observes: “The BOAC building (Gillespie Kidd & Coia) is one of my favourite buildings on Buchanan Street because it adds to that rich nature as you’re walking down the hill the blonde and red buildings march past and then suddenly there’s a gap with this dark profiled building. The way it meets the ground is testing something different.”

Does the great vitality of Glasgow lie in the fact that it has never been afraid to swing the demolition ball at anything standing in its way? Or are we too ready to sweep away the past in the name of the future? Stewart said: “We live in a society which is very aware of recycling. The concrete, for good or bad, has embodied carbon in it, for us to sweep aside an ugly building and say ‘let’s replace it’, you’ve got to be content with the justification. Part of the stigmatisation is the belief that these are energy-hungry buildings and always will be so it’s best to get rid of them.”

Of course, divisiveness isn’t necessarily a bad thing and splitting opinions at least gets people talking. Contrast that with some of the new developments we see such as the Maldron Hotel. Architecture has a concrete problem and we certainly shouldn’t be demolishing on aesthetic grounds but what if the buildings are poorly laid out and don’t lend themselves to conversion? If there is an economic case then surely demolition should be on the table. Stewart answered: “We’re working on New Zealand House in London, a grade II listed building and we’re taking all the cladding off, reconfiguring it and putting it back exactly as it was in the early 1960s. When you look at the building it appears exactly as you saw it when it first opened but it has all the performance benefits of double glazing and thermal values that meet the latest building regulations.” Can we learn something from the era, have we forgotten how to build solid chunk buildings where you just leave them alone and they don’t fall apart?

“It’s the vision not just of the architect but the developer and the tenant, the tenant drives some of the aesthetics”, says Stewart. “A tenant is now looking for Class A sustainability and all the credentials that they can lease, which leads the developer to think a certain way and appoint an architect who can provide that. The tricky part is ensuring as a community we are all aware of issues with modern methods of construction. Unfortunately, Glasgow has recently taken a different approach where it’s all curtain wall systems and lots of glass. If you go down to the financial district there are big new office developments which don’t echo the spirit of Glasgow. You wouldn’t look at these in isolation and say they are Scottish buildings.”

Are today’s glass boxes a reaction against Brutalism and the mistakes of the past? Are developers/architects so traumatised by the public backlash that the priority is to be as bland as possible and ruffle no feathers? Stewart said: “Every architect is capable of creating something excellent. They are limited by budget and developer aspirations to maximise net internal area. It’s about the thinnest piece of cladding to seal the deal on building regulations and unfortunately, some of these buildings are built with wafer-thin cladding and are characterless as a result. In a place as rich and steeped in history as Glasgow, it is inappropriate to pull some of the stuff that’s happening and it’s detracting from the city’s iconic buildings. We had a voice and we’ve lost that voice.”

Historic Environment Scotland recently turned down a request to list the Cumbernauld town centre megastructure, highlighting the real and present danger facing even the best-known structures. In a sign that matters may be starting to change however the listing process is being harnessed to protect other notable examples such as the Leith Banana flats, the Castle Terrace car park in Edinburgh and a swathe of Aberdeen’s high-rise heritage. Halliday added: “One of the sad losses was the Bank of Scotland Building by TP Bennett (Ingram Street). It looked stunning and fitted beautifully into that corner block.” Referencing comments made by housing and levelling up secretary Michael Gove, who has pledged to ‘prioritise beauty’.

Halliday adds: “There is a political dimension to this. Building beautifully is code for classical.” It is a heartening sign that sentiment might finally be turning in an area where passions too often overrule the head. Erasing history on aesthetic grounds, the equivalent of book burning, is no longer tenable. A more holistic approach, embracing environmental considerations, is long overdue.

|

|