RSH+P: Materially Different

22 Apr 2022

Following the passing of Richard Rogers Peter Wilson; architect, writer and founding director of the mass timber academy, outlines the hidden timber architecture which underpins a practice better known as hi-tech visionaries of concrete, glass and steel.

The name Richard Rogers is generally associated with a type of architecture formed from ‘modern’ materials - concrete, glass and steel. Yet the practices that have borne his name - Richard Rogers + Partners, succeeded by Rogers Stirk Harbour and Partners - have a hugely commendable but largely unheralded portfolio of projects that make exemplary use of engineered timber in hybrid relationships with the ‘high tech’ architecture for which they have been famed. The lineage of these buildings goes back over 20 years, with the developmental thinking underlying the use of modern timber technologies in their design arguably providing a masterclass in the continual refinement of knowledge and application of glue laminated timbers to create highly articulated architectural forms.

Few would argue that Richard Rogers was one of the most remarkable architects of his generation. His impact on architecture was imprinted on the world with the competition-winning project for the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris that he designed in collaboration with Renzo Piano*. The relationship between the Centre’s served and servant spaces - and the device of taking vertical circulation onto the outer surface of the building - reappeared in the Lloyds of London building (1978-86) in an even more dramatic machine aesthetic and, much later in the Mossbourne Community Academy (2002-04), the practice’s first visible venture in the UK into the use of engineered timber in modular form.

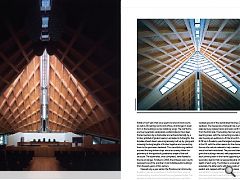

The introduction of timber into what has otherwise come to be widely seen as the Richard Rogers + Partners’ ‘hi-tech’ architecture had manifested itself much earlier, however, in the international competition-winning design for the Law Courts in Bordeaux (1992-98). Its precise technological frame articulated once more the ‘served and servant’ conceptual approach and the practice’s continuing desire to deliver transparency of function, this time with the peaks of seven timber-lined and clad conical courtroom chambers piercing the undulating, vaulted bays of the building’s oversailing roof. An extraordinary and much under-publicised urban structure in the Roger’s ouevre, the organisational form of the Law Courts has been reinterpreted in different ways in a number of subsequent projects in which timber has played a prominent role, not least in the Macallan Distillery. It also signalled the beginning of the practice’s interest in creating low-energy hybrid public buildings.

An anonymous, open competition win in 1998 for the new Law Courts in Antwerp took the integration of engineered timber into predominantly steel and glass structures in a new direction - this time within the shimmering stainless steel-clad flotilla of roof ‘sails’ that cover eight civil and criminal courts as well as 36 hearing rooms and offices, all arranged in linear form in the building’s six low radiating wings. The roof forms are true hyperbolic paraboloids, prefabricated in four steel-framed sections by a shipbuilder and echoed internally by a timber gridshell of glulam beams. Laminated in full lengths, the lamellae of each beam was progressively built up by gluing and screwing the long lengths of timber together and connecting them to the perimeter steelwork. This manufacturing method ensured the long timber strips would accurately follow the geometry of the hyperbolic paraboloid shape of the roof structure. The assemblies, once completed, were floated to the site on barges. Finished in 2005, the Antwerp Law Courts represent one of the practice’s most notable public buildings from the early years of this century.

Opened only a year earlier, the Mossbourne Community Academy marked a milestone in the Partnership’s work: an entire building structure formed from engineered timber. The decision to take this constructional route arose in part from the need for a structure lightweight enough to sit astride the rubbled ground of the demolished Hackney Downs School it replaced. The inauspicious triangular site is enclosed on two sides by busy railway tracks and looks north to the Downs from the third side. The building has two wings that enclose the teaching areas, with the connecting knuckle in the V-shaped plan housing an auditorium. At the time of its construction, the 8,312 sq.m Academy was the largest engineered timber frame in the UK, with the other reason for the choice of material being the use of a natural material to help create an environment that would not feel institutional. The post and beam external frame gives the building a rational, well proportioned presence with each primary beam in the frame supporting the ends of deep secondary beams that run perpendicularly into and through the depth of each wing. The timber is uncovered internally as well as externally, the latter parts with three coats of weatherproofing sealant and capped with hardwood in places that are especially susceptible to the elements. The exposed galvanised metal staircases that lead to each of the Academy’s three floor levels are hung off the internal elevations of each wing’s post and beam structure in a manner reminiscent of the escalators that provide the theatrical frontage to Centre George Pompidou.

The National Assembly for Wales (the Senedd, 1998-2005) is perhaps the most visible use of timber by the Partnership in a public building in the UK, but can be seen to reprise a theme first begun in Bordeaux - a concave floating steel-framed roof containing six convex, oval indentations, the soffit of its entirety a masterclass in curved, open jointed western red cedar cladding. The ‘funnel’ that sits over the Parliament’s debating chamber rises through the building’s main public level to penetrate the fifth of the six roof indentations is similarly clad and clearly marks the location of the chamber to visitors approaching or entering the building. There is no structural use of timber here, but the presence of the material is a prime feature of the building.

A change of name to Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners in 2007 saw little change to the lineage of timber utilisation in the practice’s projects, with now-recognisable themes continuing to appear. Schematically, the Bodegas Protos winery in Penafiel, Spain has a sectional diagram similar to the Senedd building: a deep concrete base level, transparent middle and an undulating roof above. The superstructure this time, though, is entirely of wood. Occupying a triangular site, five interlinked parabolic vaults that diminish in length within the triangular site constraints are each formed from a series of arched glulam beams, surmounted by longitudinal beams held ‘afloat by steel ‘V’-shaped props. These straight beams support further arched beams that are shaped as closely as possible to an inverted catenary curve and on which sit timber sandwich panels and terracotta tiles. In recognition of its structural ingenuity and precision, the building won the RIBAs European Award and was shortlisted for the Stirling Prize on its completion in 2008.

Still in Spain, the Las Arenas development in Barcelona finished in 2011 after more than a decade of work. This transformation of the long disused late 19th century bullring (designed by Lluis Domenech i Montaner) was a massive project in which the building’s perimeter wall was retained whilst the whole of the former interior was entirely scooped out to allow multiple levels to be inserted. The topmost (fifth floor) level is a steel-framed dish housing a multi-purpose space and public deck, over which floats a vast timber gridshell roof formed from primary and secondary glulam beams and Kerto® (LVL) panels, all connected by flitch plates and dowels to give the appearance of a continuous timber structure. The shallowness of the gridshell (80m diameter and 8.5m deep) required an ingenious engineering solution to prevent buckling and large deflections. As with all the projects discussed here, from the Antwerp Law Courts onwards, the relationship between the practice and the project’s structural engineers produced a dramatic, innovative engineered timber response to a complex technical challenge.

The most recent timber project in the sequence is the multi-award-winning Macallan Distillery at Craigellachie, on Speyside (completed 2018). Here, many of the themes and lessons from previous projects have been brought together to produce one of the largest and most complex timber buildings ever constructed in the UK. Like the Senedd and the Bodegas Protos winery, the sectional transparency and horizontal layering of the building is self-evident from the building’s exterior, as is the organisation of the plan into five linearly-arranged grass-topped domes. Beneath, a magnificent gridshell structure is the pièce de résistance of the project: the roof is 207 metres long, 13,620sq.m in area and made up of hybrid timber beams in 27m, 12m and 3m lengths. each of which is 200mm thick and,

in most cases, 750mm deep. This is no simple repetitive construction, however, but an extraordinarily sophisticated demonstration of advanced timber technology utilising 1,798 separate beams and 2,447 triangular timber decks within an overall roof package comprised of 350,000 bar-coded pieces (including fixings) almost all of which are different. Despite the obvious logistical challenges, the roof was completed within six months of the March 2016 start date, using only 20 installers and two cranes to carry out 4,245 lifts. Any description of the engineered timber structure, however, is wholly inadequate to what the visitor experiences on entering this building and looking upwards: the practice’s 20+ years of experimentation and innovation in the use of engineered timber has produced an exemplar modern timber building, setting a very high bar for others to aspire to.

* The winning team was an unknown group made up of Gianni Franchini, Ted Happold, Renzo Piano, Richard and Su Rogers

|

|