La Petite Ceinture: The French Line

22 Apr 2022

Disused urban railways have long been obvious candidates for bike paths but a new generation of projects inspired by the success of the High Line in Manhattan are taking the idea up a level by incorporating urban farms and linear parks. Leading the way is the city of Paris with La Petite Ceinture, a circular railway that is being brought back to life as the world’s longest urban park. Mark Chalmers keeps us in the loop.

It turns out that 2018 was a good time to visit Paris. Covid wasn’t even a gleam in an epidemiologist’s eye and the gilets jaunes hadn’t got into their stride – but it was the 50th anniversary of the événements of May 1968, protests which for a brief moment promised to upend French society. In July 2018, the Île-de-France was also in the grip of a canicule and temperatures reached the high thirties. I stayed at Louveciennes, a five minute walk from the point where Sisley painted the Seine, and explored the city using the RER system of suburban railways. Later, as the day’s heat dissipated, I wandered along the riverbank to sit under the trees beside the Machine de Marly. There are over 20,000 Parisians per square kilometre.

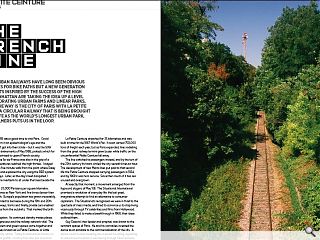

Paris is twice as dense as New York and five times denser than Berlin or Edinburgh. Europe’s population has grown inexorably, yet city density tended to decrease during the 19th and 20th centuries once railways, trams and finally private cars enabled people to commute from the outskirts. That marked the birth of urban sprawl. Paris is an exception. Its continued density makes places like Louveciennes precious and the railway network vital. The city’s transport system and green spaces come together and clash where a railway known as La Petite Ceinture, or Little Belt, encircles the city centre. Today its abandoned tracks run along a backdrop of graffiti, construction sites and industrial wastelands. La Petite Ceinture stretched for 35 kilometres and was built in time for the 1867 World’s Fair.

It soon carried 750,000 tons of freight each year, but as Paris expanded, lines radiating from the great railway termini grew busier while traffic on the circumferential Petite Ceinture fell away. The line switched to passengers instead, and by the turn of the 20th century its trains circled the city several times an hour. The development of new Métro lines put paid to that second life: the Petite Ceinture stopped carrying passengers in 1934, and by 1969 it was hors service. Since then much of it has lain unused and overgrown. At exactly that moment, a movement emerged from the hype and slogans of May ‘68. The Situationist International promised a revolution of everyday life: the last great, imaginative attempt to find an alternative to consumer capitalism. The Situationists recognised we were in thrall to the spectacle of mass media, and tried to convince us to stop living vicariously through TV celebrities and films from Hollywood. While they failed to make a breakthrough in 1968, their ideas outlived them. Guy Debord, their leader and prophet, was drawn to the remnant spaces of Paris. He and his comrades invented the dérive as an antidote to the commercialisation of the city.

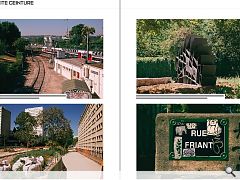

A dérive could involve breaking into a derelict building, exploring an abandoned hospital or wandering through Père Lachaise cemetery. So off they went down back streets and through deserted parks, clambering over walls to see what they could discover. To Debord, “The lessons drawn from dérives enables us to draft the first surveys of the psycho-geographical articulations of the modern city”. He even had a go at re-drawing the city plan. His Naked City map of 1955 was published in the Psychogeographic Guide to Paris, identifying locations which could be explored with a particular frame of mind intended to draw out their ambience. Most of the remnant spaces which Debord sought out are long gone, built over and developed for profit, like the old slaughterhouses at Parc de la Vilette or the Renault factory at Île Seguin, but stretches of La Petite Ceinture remain as an overgrown wasteland running through, above and below the city. Inspired by the Situationists, I walked along a back street in the 15th arrondissement until I found a gap in the fence with a glint of railway track far below. I squeezed through, then skidded on my backside down a sheer slope which I knew I’d struggle to climb back up – but I knew there was bound to be an easier way to escape. There always is. This was one of the long-abandoned sections of the Petite Ceinture. After 1969, much was retained as a railway – firstly for the movement of rolling stock, and later held in reserve by SNCF, the state-owned railway company. Ten years later, stretches were incorporated into the construction of the ‘C’ line of the RER (Réseau Express Régional), the regional rapid transit system which serves Paris.

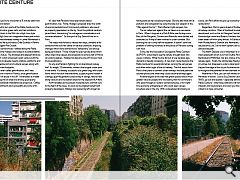

Today around 23 kilometres remains unused, extending clockwise from Batignolles in the 17th arrondissement to the banks of the Seine in the 15th. In theory it’s possible to walk along its entire length; in practice that’s tricky thanks to fenced-off tunnels and crossings with live railway lines. For the past fifty years, Paris has been figuring out how to use this unique landbank. Until recently, La Petite Ceinture was the domain of underground explorers or cataphiles and the graffiti writers who haunt the Métro system. The catacombs run for kilometres through the limestone underbelly of Paris, and one access is a discreet manhole just inside the darkness of a portal to one of La Petite Ceinture’s tunnels. Gradually the abandoned railway was encroached on by the city. In 2008, a stretch between the Porte d’Auteuil and the Gare de Passy-la-Muette became a sentier nature or nature trail but the mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, had far greater ambitions. She plans to turn the French capital into La Ville Du Quart D’Heure, which sounds much more attractive than a “Twenty-Minute City”.

Thanks to Paris’s density, it’s relatively easy to ensure that you’re no more than a 15 minute walk from the shops, school and station. Hidalgo planned to turn parts of the Petite Ceinture in the 16th arrondissement into a green path, and had ambitions to turn an elevated track in the 15th into a High Line-style promenade. The High Line is an imaginative linear park which re-uses an abandoned elevated railway in Lower Manhattan: it was brought back to life by architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro with landscape designer Piet Oudolf. But around the same time as I walked along the Petite Ceinture’s tracks, Anne Hidalgo was locked in a political battle royal over the line’s future. The trackbed and adjacent land are still owned by SNCF, which proposed a joint venture with the Municipality of Paris to develop twenty stations, platforms and tunnels into bars, restaurants and cultural venues, along with green spaces and more footpaths. This process is often called gentrification, and I was fascinated to see how it works in France, since gentrification has become a term of abuse in the UK. It translates as middle class people moving into an area and driving up property values so that its traditional inhabitants are priced out. Coffee bars, expensive apartments and cycle paths are some of its outriders.

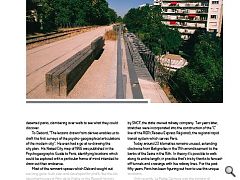

It’s clear that Parisians have reservations about gentrification, too. Firstly, Hidalgo’s proposal drew the wrath of environmentalists and Communist politicians, who saw it as property speculation on the sly. Soon the political centrists joined them, denouncing “an outrageous concretisation and commercialisation”. So the spirit of Guy Debord lives on in Paris. The mayor was forced to retrace her steps, unheard of for someone who built her career on tactical urbanism, imposing changes which were claimed to be “temporary” but end up being permanent. Those include the pop-up bike lanes which other cities have copied, and proposals to remove half of Paris’s car parking spaces. Hidalgo has become one of France’s most divisive politicians. So why are Parisians fighting for an abandoned railway line? Its length, 23 kilometres, makes it the longest urban park in the world. It’s already successful as a green lung, with urban farms which function like allotments, sculpture parks hidden in cuttings, guerrilla gardens tucked away in sidings, nature trails along viaducts and recreation areas for the adjacent HLM flats.

HLM translates as housing at moderate rent, and that cuts to the heart of the issue. As soon as she aligned herself with property developers, Hidalgo was viewed by left-wingers as having sold out her socialist principles. But she also took aim at pollution and congestion by using the bike as a weapon in the “War against the Car”. That inflamed right-wingers, too. The so-called war against the car takes on a new sense in Paris. When I stopped at a Park & Ride near Aulnay-sous-Bois, all the Peugeots, Citroëns and Renaults were dented and scratched, as if they’d been involved in urban combat. But banning the car is only half the equation: it doesn’t solve the problem of shifting hundreds of thousands of Parisians during rush hour. Some, like the Association Sauvegarde Petite Ceinture (ASPCRF), would like to see the railway brought back into use as a railway. While the line fell out of use decades ago, demand is steadily increasing.

A new tram route shadows the Petite Ceinture for several kilometres, serving the same areas and often within sight of the old railway. The first lesson from Paris is that plans to convert urban railways into bike paths are counter-productive when they could become railways again. Another aspect is the idea that green spaces have a much greater value to people who live nearby, than for commuters who pass through en route to somewhere else, or for night-time economy entrepreneurs who could open venues anywhere else in the city. With undeveloped land being so scarce, can Paris afford to give up its biodiversity for bars and restaurants? Regardless, Paris is years ahead of Scotland in the re-use of railway corridors. Miles of trackbed lie under-used or simply abandoned, such as the old Glasgow Central Line through Kelvinbridge tunnel and Botanic Gardens station which has been sealed off with spiky fences. In Edinburgh, the old tracks from Murrayfield to Granton and Newhaven, which might one day become Line 2 of the tram system, are currently an under-utilised bike path. The North Deeside Line in Aberdeen is similar, an interrupted path which runs from Duthie Park through Cults, Bieldside and Milltimber, has less chance of becoming an active railway again.

Finally the old Dundee-Newtyle Line is walkable in Lochee, but disappears under a retail park to re-emerge beyond the edge of the city at Auchterhouse. All four cities fail to recognise the potential of their dormant railways. Meantime in Paris, you can still witness the Situationist Manifesto in action. Just as Guy Debord cautioned in the 1960’s, go out and explore – especially leftover places like the Petite Ceinture – otherwise politicians will hand them to special interests and big business, and soon you’ll be reduced from a citizen to a mere consumer.

|

|