GUDP: Constructive Voice

21 Apr 2022

Squaring the circle of commercial imperatives and sustainable design is the bread and butter of the Glasgow Urban Design Panel, an altruistic body championing architecture and placemaking to developers, designers and planners. But how is its work being shaped by the pandemic and ballooning inflation?

Urban design panels are surprisingly thin on the ground worldwide but Glasgow stands apart with a participatory panel drawing on organisations as varied as the Mackintosh School of Architecture and Historic Environment Scotland. Lauding the most established design panel in Scotland Raffaele Esposito, City Design Manager at Glasgow City Council said: “When I started to look into urban design panels in the UK I was surprised to discover that there are a lot of attempts to create panels, but very few are regularly up and running. Notwithstanding what the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) has been doing down south.”

Building on the groundwork laid by his predecessor, Gerry Grams, Esposito speaks passionately of ‘creating discussions and opportunities to open up design as a process of ideas, rather than a process of individuals.’ But how to marry these ideals in what can be a confrontational process where the interests of applicants and neighbours rarely align. How does the panel foster a more collegiate approach? Esposito acknowledged “It’s been a journey,” but believes today’s panellists embody the spirit of free-thinking like never before, in part spurred by pandemic related changes that have brought in more outside talent.

Esposito says: “What has happened in the last two years is amazing, we’ve moved from face-to-face personal meetings to a digital environment and that has allowed us to bring in people from outside. They are not ingrained in those dynamics that were perhaps more typical of the panel of a few years ago. Even just one new panellist from down south brings a completely different dynamic. It brings the conversation onto a more objective plane.”

An influx of talent is held as introducing a more holistic view where local repercussions are weighed against the impact on the city and the region as a whole. “Being passionate and avoiding individualism is fundamental and that comes down to knowledge,” says Esposito, well aware of the risks inherent in going too far, too fast, on digital. “Embracing digital is not for everyone. I believe that 90% of our panellists are very comfortable with that format but embracing digital automatically cuts off older people. It’s a bit like what you’re seeing in planning where so many consultations are now online, although planning is still trying to retain a hybrid approach.”

To that end, Esposito champions ongoing engagement with communities on the ground, even if only in the form of a site visit, suggesting that more radical options for boosting engagement such as a physical ‘shop window’ for discussions remain off the table for now. Another advantage of digital is reducing the chances of one personality dominating, a realisation that underpinned the shift even before the pandemic. “We were adamant that we didn’t want to stop during the pandemic”, says Esposito: “ To keep the urban design panel going was the most impactful way to demonstrate that the city was not stopping. As long as people were submitting applications, we were still active. The shift to digital was forced but the benefit of it was so obvious that we decided immediately to capitalise on that. Actually, not just to translate into digital the previous format but to embrace all the possibilities that this new tool can give us.”

Embracing technologies such as Vu.City, a planning platform for sharing design proposals interactively and the polling app Slido the GUDP is experimenting with new ways of visualising data and democratising discussions to ensure that everyone’s voice is heard. “There is something else that I believe is extremely fascinating,” observes Esposito, “which is the idea that gathering data gives us the chance to put in place a governance system that allows us to review the effectiveness of the process. Until the lockdown, the process was more empirical because it was based on impressions but now it’s very scientific.”

Will this help in terms of transparency? How can people view the GUDP in action and see not just outcomes but the processes behind decisions made? “We are constantly inviting people to engage, we’re not precious. However, there must be some sort of filtering because we can’t allow everyone to participate.” Is there scope for having a paid position for the panellists? “Would it be appropriate? Absolutely. Yes, because that will increase the professionalism of actors and improve accountability, which is not a small thing”, notes Esposito. “Is there scope? No chance. GCC is not in a financial position to even imagine the possibility of being able to pay panellists. I don’t take for granted that people are giving their time for free.”

I understand that projects put forward for review are voluntary, could there be some system where specific projects are mandated for review? Esposito answered: “Although it’s hosted by GCC, in the planning department this process is independent, it’s not statutory. It’s not like Edinburgh where the panel reviews are directly connected to the planning procedure. In Glasgow, they’re not and they are not because we always wanted to retain a very clear line of demarcation between the process of independent review and the planning process.”

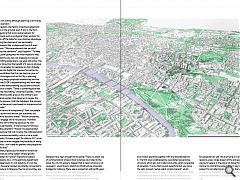

“All the major schemes that recently came to the fore in Glasgow have been brought to the panel. There is a direct line of communication where critical schemes are invited to the panel. So, it’s not going to happen that a major scheme is not reviewed. I would love to stretch to infrastructure proposals, bridges for instance. There was a connection with A+DS years ago that allowed us to nominate infrastructure schemes for review but that service isn’t provided anymore.”

Outlining what drives the panel, Esposito cites three areas that govern its approach; ethical standards, knowledge and modus operandi together with the rationale behind it. The first area is addressed by a published governance structure which sets out in black and white what is expected of panellists. “I know that sounds superficial but you know the Latin proverb ‘verba volant, scripta manent’, which means spoken words fly away, written words remain. CABE established that there must be an ethical constitution for designers so we are just literally adopting that approach.

“We have a code of conduct not just for panellists, but for presenters as well. We are trying to ‘control’ (for the right reasons), every single aspect of the proceedings because we like to believe in the power of doing things in a certain manner to control the output. When I say to control the output I’m not referring to controlling the type of response to a scheme. I’m referring to the fact that we are trying to maximise the benefit for the presenters and the panellists as well.”

At the heart of the panel is knowledge and the difficult task of finding the best people for any given review where multi-disciplinary panellists can have varying degrees of experience. How do you go about managing different skill sets in a high-pressure environment where every planning application is a potential scandal. “There is the knowledge that we can pull on a session basis to respond to specific schemes. So for instance, if there is a school involved we would like to take on board someone with specific expertise in school design. But there is also the knowledge that needs to grow between panellists.”

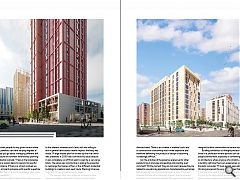

Asked about specific projects where the panel has made a difference Esposito wouldn’t be drawn without speaking to the relevant reviewers and clients but was willing to talk in general terms about recent impacts the body has made. “A large master plan for an area by the river which was presented in 2020 had a connectivity issue because it was completely cut off from east to west by a very large block. The panel was constructive in asking the presenter to rearrange the masses of four or five different residential buildings to create an east-west route. Planning times are huge but it’s being finalised as we speak.”

“You can ask how many times we succeed on that journey, probably a few times. There is a harsh reality out there and it’s becoming harsher as the pandemic demonstrated. There is an increase in material costs and so construction is becoming much more expensive and therefore defending the product of design is becoming increasingly difficult.”

Can the activities of the panel be opened up for other people to log in and view proceedings and possibly even comment? “At the moment they are not open because they are related to pre-planning applications characterised by extremely high sensitivity from a commercial point of view. These are schemes that are not in the public domain, they’re not even published on the planning website. We want to discuss design at an early stage and there is a planning process there which is designed to allow communities to have an input.”

Building consensus is a fraught process at the best of times in a profession where opinions can be as varied as the people behind them, especially in something as every day as architecture where anyone who inhabits, passes or visits a building will have their own experiences and preferences. Esposito concedes: “If more people were able to access that thinking process at the very early stages that would be ideal.” If that were the case it might be beneficial not just to the city but to the applicants themselves by motivating them to improve their schemes for the benefit of the economy and society.

|

|