COP26: Zero Hour

21 Jan 2022

Urban Realm reports on the built environment ramifications of COP26 with a series of articles exploring how the built environment sector is galvanising its response. We begin with a look at how net zero and circular design is reshaping our schools, homes and public spaces.

While the echoes of the COP26 climate conference continue to reverberate, Urban Realm assesses the implications for the built environment sector which is still scrabbling to make good on promises of change with a plethora of initiatives from net-zero schools to circular housing and efforts to retrofit public spaces as offices. With the consensus that matters must change - and fast, how is the construction sector rebuilding its structures and systems to meet the challenge of a generation? At the epicentre of the COP26 proceedings was Stephen Good, chief executive of the Construction Scotland Innovation Centre (CSIC), who is on a mission to embrace the materials and technologies that will build a greener future and sooner rather than later.

He told Urban Realm: “We’ve got to decarbonise materials and the built environment generally and part of that is going to be looking at embodied carbon credentials. How do we decarbonise cement and steel? A lot of people are switching onto the idea that we’ve already got a wonder material in timber if we could only get it to do more things. That’s part of what we’ve been working on here, how do you create higher-value timber products?”

Good harbours ambitions of seeding a hi-tech revolution in which low carbon technologies come to the rescue bearing in mind it’s not just the environment that’s in crisis but the economy too with a materials shortage, supply crunch, inflation and labour shortages. Are these issues prompting people to appraise locally sourced timber and indigenous manufacturing capacity in a new light? Good said: “Since the beginning of the pandemic we’ve focussed on how to onshore our protective equipment capabilities. That’s one of the headline outcomes from the early pandemic, when it was about how do we get industry restarted, to the middle of the pandemic when it moved from how do we recover to how do we transform the industry to make it as resilient as possible.”

The COP26 conference dovetailed nicely with these aims but the CSIC hasn’t created anything specifically for the conference, choosing instead to use it as a springboard to showcase a suite of projects which have been bubbling away for several years including NearHome, a prototype examining the future of work and a zero-carbon schools project for the UK government which utilises homegrown cross-laminated timber as the core structural component. Good added: “COP being delayed from last year has probably been a blessing from our point of view because it means these projects are at a stage where we can showcase what’s going on, people can walk around and experience them rather than just hearing about them.”

Amidst all the talk is the publicity helping to advance the sustainability cause? “We’ve had one of Scotland’s largest private housebuilders here looking at how they can adopt zero carbon off-site solutions”, notes Good. “House building and retrofit are climbing up the agenda and that will help people figure out how to make processes better and public sector clients are setting up processes that drive net-zero outcomes rather than cheapest quotes. I don’t see the built environment disappearing back into the shadows as although we are one of the biggest contributors to emissions, we are also one of the biggest providers of solutions.” Taking these issues forward is the Sussed environmental consultancy, a joint venture between Holmes Miller Architects and John Gilbert Architects to scale up delivery of Passivhaus and low energy buildings to drive down costs. Explaining the genesis of Sussed to Urban Realm co-founder Matt Bridgestock said: “Both ourselves and Holmes Miller felt there was an opportunity in steering the tanker of much bigger buildings. The partnership with Holmes Miller brings that expertise to a fresh audience without losing the ability to innovate, change and move. We’re installing monitoring equipment in buildings that provide hourly information on how the building is performing and reacting to the environment.” Another strand in sustainability is diversity with a widespread understanding that improvements in one go hand in hand with the other, a particular passion for Good: “We’ve not got our act together quite yet on the diversity challenge but there are a lot of good things happening to ensure the industry establishes itself as a positive destination for anybody. I’ve never met a female engineer who doesn’t like engineering but I’ve met plenty of female engineers who don’t like the way the industry is structured.”

Do we require further regulatory change, are we pushing hard and fast enough? What still needs to happen to bring about the required change at scale? “Legislation and regulation create a level playing field so everyone has to figure this out together,” says Good. “We need building regulations to be as tough as they can be to get us where we need to go otherwise it’s easy for people to say they’re meeting minimum standards. It’s a crisis that we’re facing, we knew what we had to do to tackle the recent health crisis. That is the mentality that must be adopted. It’s about using incentives, legislation, regulation and procurement to drive outcomes that we want.” When people discuss the climate crisis it tends to be framed in negative terms. ‘It’s our fault’, ‘it’s our problem’... but should we be looking at this as an opportunity to overhaul entrenched ways of working?

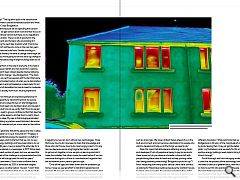

Bridgestock said: “The construction industry has to change whether it does so by choice or through force. We’d rather do it right. There will be things that are changed by legislation but it’s better to bring people with you and move things forward positively. Sustainability is seen in terms of what we’ve lost, we’re trying to show the benefits. It’s not looking at what we can’t do but the possibilities of places that are better ventilated, more efficient and healthier.” What will this new architecture look like, is it a move away from concrete and an embrace of natural materials? “It’s an evolution of some of the modernist ideas,” continues Bridgestock. “There’s a lot more emphasis on building physics and that takes you down the route of natural materials, and designing around daylight in ways that don’t lead to overheating. It acknowledges that people need control over their environment. At the heart of it is a site-specific analysis that’s woven into the building. Form and shape are tested against loss of heat, overheating and shading and we come to something that works better environmentally through a process of knowledge rather than guesswork. The architecture becomes rational because it’s backed by physics, there is more emphasis on windows and their shape, the daylight and the ventilation provided as well as what you can see out of it and the look of the building. All of those aspects are brought together at a detailed level to give a more usable building. We don’t have to modify the environment.” The post-war era was all about engineers and architects bending the environment to their will through brute force. Do we need to learn humility and pre-industrial techniques, ways of working with the land and what nature provides for the post-carbon era? “It’s embracing Modernism but rejecting the international style,” says Bridgestock.

“The idea of Modernism was one size fits all wherever it is but what we are talking about is location and climate-specific. We’re working on schools in Hertfordshire and the Highlands, the brief for both of those is the same but the climate demands a completely different response to orientation layout and daylighting. Good architects excel at that so this should demonstrate how good architecture works.” With data and processing power influencing design to an unprecedented degree are we witnessing the birth of a new architecture where aesthetics take a back seat to energy performance, daylighting hours and operating efficiency? Is there an inherent risk in being driven to such a large extent by the numbers or is it liberating to be freed from style wars to focus on measurement and quantifiable metrics? Bridgestock responded: “It isn’t all about number crunching, there is still an art to making places and architecture.”

So-called ‘eco-buildings’ can make a mockery of the system when you look at the actual construction and the volumes of concrete and steel employed. Do we need to recalibrate towards whole-life performance and is the urgency such that we have to prioritise cutting carbon now? How do we prioritise the reuse of existing buildings? “The big blind spot in the construction industry at the moment is around embodied carbon and what we’re building from”, says Bridgestock. “That’s important because we are spending that carbon now. It’s important we get carbon down now and then focus on the long term operational carbon but there are no regulations around embodied carbon. There is a lot of goodwill in the industry and the clients and funders who are looking at it but nobody is taking the next step towards what it has to be. The sea change which will have to come in the next ten years is around the materials we build from. Smaller buildings in Scotland are timber-framed, the level of change there might be relatively modest but we’re going to have to see a big change in the methods and manufacturing of larger buildings built out of concrete and steel.”

A longstanding thorn in the side of everyone in the field is the imbalance between retrofit and new build VAT, a glaring discrepancy that hasn’t been closed despite intense lobbying. “I do think that’s got to change,” says Bridgestock. “The track that we need to be on can’t be squared with the fact that we’re demolishing. The embodied carbon of what you’ve demolished needs to be factored in and not treated as a clean slate. It’s not to say that’s the end of demolition but we do need to moderate and interrogate as a society how much we are prepared to tolerate.” How do we punch through an engrained preference for new build, not necessarily by refurbishment but by reusing concrete foundations and steel frames on-site? Bridgestock answers: “ An I-section beam can be taken down and reused in a different building but how do we verify that? How do we get the paperwork we need to give us confidence that that steel has been tested. It would be easier to do that than to melt it down and turn it back into steel. My view is that bringing embodied carbon into the building regulations would kickstart discussion around the reuse of material and put some value on demolition material.” Is Bridgestock optimistic that all the pieces are now in place for a genuine revolution or is it just more hot air?

“Progress is being made on operational energy, the question is whether it is fast enough. I always point to the fact that we can do very low operational energy buildings and have been able to do so for the past 20 or 30 years. I saw an advert the other day for a heat pump that was placed in a newspaper in 1977. We’ve been able to do it for a good number of years but now we need the will to do it. The scale of the challenge is unprecedented and the construction sector will change over the next ten years.” Echoing these sentiments, Good is less confident that a target of net zero emissions by 2050 is achievable despite conceding that ‘there is no other option’. He said: “I don’t think at the current pace and direction of travel we would do it but I do see a lot changing so I am optimistic that will become more achievable. I take a lot of confidence from the fact that we already know how to build zero carbon buildings. We don’t do it regularly but we can do it without new technologies. Those that know how to do it are keen to share that knowledge and those who don’t know how to do it are hungry to learn. I’m only nervous because we are a big fragmented sector, we need to get our act together in how we join up learnings and don’t make the mistakes that others made the week before. If we can overcome the logistics of how to coordinate and organise then the foundations are in place to get this right.

“Once all the signs are taken down and the protesters go home, I hope we see real effort to transform leadership and business. My biggest wish is that we galvanise and mobilise that energy and turn it into action and delivery. We could end up in a situation where the built environment is a legacy destination for all the talent that’s going to have to move out of other sectors such as oil and gas. We have a brilliant future ahead of us in the built environment and can become a destination for people who want to develop and help us do the things we need to do.” Does this mean that attitudes are softening among clients and developers? Lots of people are happy to pay lip service to these issues but do you observe a broader cultural shift with people taking these ideas to heart and actively pushing rather than being passively pulled along? Bridgestock picks this up: “I find it reassuring how many public service clients have come to us looking for Passivhaus buildings because the Scottish Futures Trust has said we need to. It’s unlocked something they didn’t feel they could ask for before but now that kind of performance is normalised. We’re moving in the right way but then the question becomes whether we’re moving fast enough which is a different discussion.” While optimistic that we have this in hand Bridgestock is still wary of the magnitude of what still has to be done, fearing that it may yet get the better of us.

“There are pilots, my frustration is are we ready for this at scale. Passivhaus and low energy buildings need scale to bring the cost down and drive it through.” For all the angst and hand-wringing evident at COP26 it is clear that we possess all the technology, tools and skills that we need to take us to greener lands, with the focus now resting on how to put this into practice. With the easy pledges made the hard challenge begins in putting them into practice but as recent months have shown there’s nothing like a good crisis to focus minds. The fact remains that sustainability doesn’t start and stop at the petrol pump but is intrinsic to our everyday lives.

|

|