Cove Park: Curve Appeal

20 Jan 2022

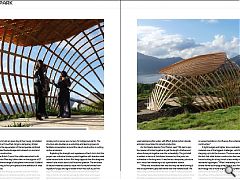

A curvilinear timber lattice classroom in Argyll has the ambitious task of seeding root and branch reform of construction by educating visitors on the lengths timber technology can go in response to a climate crisis that requires each of us to come out of our shell.

Arc Architects are to host an open day at their newly completed outdoor classroom at Cove Park, Argyll, a temporary timber pavilion to discuss the rejuvenation of the temperate rainforest which once carpeted the landscape and ushered in a root and branch reform of construction. Funded by the British Council the collaborative build with architectural scientist Mae-ling Lokko drew on the support of 27 students from a diverse range of disciplines from across Scotland and Ghana, returning to first principles and the definition of what a building should be. Responding to the developing climate crisis the initiative re-uses the foundations of a previous building, which store the equivalent of 14 tons of carbon, to support a curvilinear timber lattice that mimics the shade and shelter provided by a forest canopy and so serves as a nursery for indigenous plants.

The structure also doubles as a workshop and learning space to facilitate conversations around the role of construction in cutting carbon emissions. Exploiting the strength and suppleness of larch to its limit the project saw individual timbers joined together with stainless steel cable ties and bolts to form 16m long supports that the designers weren’t sure would stand until fixed into position. The embrace of natural materials extends inside with furniture formed from mycelium fungus and agro-waste which was built in just five days. Illustrating how construction can transition away from high emission concrete by pioneering alternative techniques, technologies and materials, the build show ways of weaning ourselves off the highly polluting material and the second most used substance after water, with 8% of global carbon dioxide emissions now linked to cement production. Arc Architects director Tom Morton, said: “We had to join four pieces of timber together to get the length of lathes and where those join together was the vulnerability. The grid shell is resilient in terms of distributed stresses but the joints are vulnerable in the long term.

"It was fine as a temporary structure but it would be interesting to do a permanent version. “What was innovative here was the way we were forming it into an asymmetric grid shell rather than the material itself. We were using conventional timber but it wasn’t highly processed. You always need experimental and prototype structures to drive forward knowledge and materials technology but I don’t think anyone is ever going to live in a grid shell house. All our work on experimentation is to influence the sustainability of mass construction.” A tight budget and tighter time constraints made sourcing materials one of the biggest challenges, with Russwood stepping up to do the honours. The issue was exacerbated by the fact that while timber construction has been mainstream in house building for a long time it is less widely adopted in non-residential typologies.

“What’s interesting is how far we can take timber frame technology away from a stick frame and nail gun technology into a more engineered and prefabricated high-performance material”, says Morton. “We’ve barely scratched the surface of the potential for timber. We’re still dealing with it almost as a craft technology but there’s huge scope for it to develop as an engineered technology and so reduce our carbon footprint.” Morton warns of a failure of the timber industry to invest in the research and development necessary for the production of high-value materials, favouring the development of softwood materials for basic construction and leaving higher-value products to the import market. “It’s not that the future is highly processed materials,” says Morton.

“It needs to sit alongside low processed materials such as thinnings and other waste. The construction industry is very fragmented, to solve climate change and resource depletion all these strategies need to come together.” Is the fact that the structure can be built by unskilled hands an advantage? “I’m not arguing for a low skill construction workforce because that is also something we need to invest in. If we just rely on poorly trained people with a nail gun and low wages we’re not going to create a sustainable industry. Construction has a real problem, it’s the least diverse and least progressive industry. It’s 94% men and has a suicide rate three times the national average so there are fundamental issues around the culture of construction.”

Championing a leadership role for women in the profession the Cove Park team observed that 83% of applications for creative participants were from women, a statistic which encourages Arc who see the need to transition from a male-dominated construction industry ‘because women are less vested in the established culture that inhibits progressive change’. “If we are to transform our profession to be fit for the 21st century there is no doubt the future is female,” says Morton. Involving young architects at home and abroad was a vital part of the process to build not just a single structure in Argyll but lasting links across continents. “We were working in a way that young architects aren’t used to,” says Morton.

“They get separated at the start of their professional training from other disciplines and I don’t think that’s healthy. It’s much more progressive to work with landscape architects, ecologists and product designers. It changed the direction of the project.” Is Morton optimistic after COP26? “You couldn’t survive in this profession unless you were relentlessly optimistic! There were problems with COP and things that were not achieved but it was good for Scotland and raised the quality of debate and hopefully, that will stimulate more action from the Scottish Government. The world is in a climate and biodiversity crisis and people still need to wake up to that. The people who are most impacted are the least wealthy and the most vulnerable. As architects, we’re meant to be good at creating futures and managing processes of change so it’s weird that construction is behind transport and energy in decarbonisation.”

A remote hillside in Argyll & Bute might seem an unlikely location for a construction revolution but the Cove Park artists residency highlights the lengths we must go to in tackling the climate emergency. The time for treading on eggshells is over, now is the moment for delivery and action.

|

|