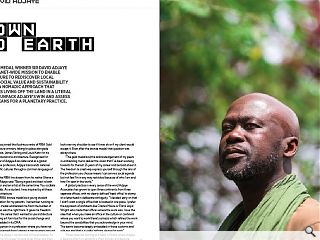

Sir David Adjaye: Down to Earth

26 Jul 2021

RIBA Gold Medal winner Sir David Adjaye is on a global mission to enable architecture to rediscover local context, social value and sustainability through a nomadic approach that emphasises living off the land in a literal sense. We unpack Adjaye’s win and assess what it means for a planetary practice.

Sir David Adjaye has joined the illustrious ranks of RIBA Gold Medal for Architecture winners, taking his place alongside the likes of Jack Coia, James Stirling and Louis Kahn for his outstanding contributions to architecture. Recognised for his roles as founder of Adjaye Associates and as a global ambassador for the profession, Adjaye transcends national borders and specific cultures through a common language of building.

Logging into the RIBA live stream from his native Ghana a visibly emotional Adjaye said: “Being a good architect is both being a constructor and an artist at the same time. You oscillate between two worlds. As a student, I was inspired by all these great names in architecture.

“Winning the RIBA bronze medal as a young student (1993) was a validation for my parents. I remember running to tell my mum! That medal unshackled me from the burden of having to prove this was the right track. It gave me freedom early and sparked the sense that I wanted to use architecture not just as a building art form but for the social change and social justice embedded in its DNA.

“As a creative person in a profession where you have not seen yourself represented there’s always a nervousness around whether what you’re doing is correct and will be accepted. As somebody on the tip of a spear I’d want to do things but then look over my shoulder to see if it was ok or if my client would accept it. Even after the bronze medal, that question was always there.

“The gold medal and the acknowledgement of my peers is unshackling me to deliver the vision that I’ve been working towards for the last 25 years of my career and be bold about it. The freedom to creatively express yourself through the lens of the profession you choose means I can serve a social agenda but not feel I’m in any way restricted because of who I am and how I’m seen in the world.”

A global practice in every sense of the word Adjaye Associates has grown to span three continents from three separate offices, with no clearly defined ‘head office’ to stamp on a letterhead in deliberate ambiguity. “I decided early on that I didn’t want a single office that is located in one place. I prefer the approach of architects like Charles Moore or Frank Lloyd Wright who made their offices where the work was. I love the idea that when you make an office in the culture or continent where you want to work there’s osmosis which refines the work beyond the sensibilities that you acknowledge in your mind. The teams become deeply embedded in those customs and cultures and that is a useful refining device for work.”

These ideas are coming to a head in Ghana where Adjaye is leading efforts to establish a West African architecture that builds on the specific history of the region, adapting it to meet the needs and standards of today. Adjaye said: “The opportunity is not for architects to do what we’ve always done and bring it over here. The continent has suffered so much of that. It’s ripe for an investigation of what the idea of architecture can be. It’s not just a project for architects of African descent, it’s a project for architecture to imagine the opportunity of culture and geography which is the foundation of the world.”

Leading by example Adjaye is pioneering the use of rammed or reinforced earth construction as a means of reducing reliance on concrete and the associated carbon dioxide emissions linked to the production of cement. “Rammed earth is the vernacular for most of the continent and is ripe for rethinking. There’s pioneering work by my colleague Diébédo Francis Kéré in Burkina Faso but I’m interested in how to use this technology to make large scale buildings.

“At the Thabo Mbeki project in South Africa, we’re creating a monumental rammed earth structure for a presidential library, something previously unheard of. It is the most abundant material on the planet and the most important for its ability to return to its original state. It has profound biophilic properties, it kills germs and insulates and I’m obsessed with it.

“What’s exciting about the continent is that there are more than green shoots. There are systemic opportunities that will lift the continent in the next 25-30 years. It’s already started.”

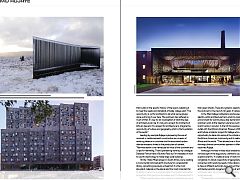

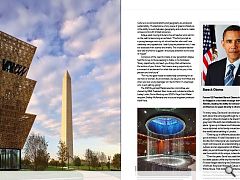

In the West Adjaye’s attentions are focused on finding an identity within architecture from which to create a dignified environment for communities, ably demonstrated by the practice’s work at the Stephen Lawrence Centre and Bernie Grant Centre in London. In the US this approach finds a grander outlet with the African American Museum of Black History and Culture, a totemic project for Adjaye who welcomed the opportunity to delve into some of the critical issues affecting the African American community and its relation to America, Africa and the world. “That allowed me to think critically about the ways diverse communities operate in different contexts,” observed Adjaye.

Although involved in these local endeavours Adjaye does not lose sight of the big picture, unafraid to couch his work in expansive terms. “It creates a body of work which is planetary, not global, it’s about a specificity of geography and culture concerned with resolving needs. It also allows a body of work to have a different authorial voice, not just the language of architecture and its range but the ability of architecture to continually learn and investigate sustainability, ecology and social pressures.

“Sustainability is the backbone of geography and culture. Culture as social sustainability and geography as ecological sustainability. The backbone of any piece of great architecture is the ability to work between geography and culture to create unique works with limited resources.

Adjaye paid moving tribute to the art teacher who set him on the path to becoming an architect. “The first prompt as a young teenager was my art school teacher who said I was creatively very capable but I didn’t pay any attention to it. I was too obsessed with science and maths. This incredible teacher said was the first to suggest I should pay attention to this side of myself.”

Conscious of the need to inspire a new generation Adjaye had this to say to those seeking to follow in his footsteps: “Every opportunity can teach you things that will become the archive of your future. That means every opportunity is a moment of excitement for what that can do for you in the present and the future.”

“For me, the gold medal is traditionally something for an old man or woman. As an architect, we say your mid-fifties are when you’re a young teenager so I like to think I’m a teenager who is just getting going!

The 2021 Royal Gold Medal selection committee was chaired by RIBA President Alan Jones and included architects Lesley Lokko, Dorte Mandrup and 2020’s Royal Gold Medal recipient Shelley McNamara and structural engineer professor Hanif Kara.

|

|