Homlea Primary: Shining Light

20 Apr 2021

A historic school in Glasgow’s south side has been brought back from the brink courtesy of an enlightened developer and architect. Delivering more than homes the story of its revival serves as a template for rescuing other abandoned schools, as Urban Realm finds.

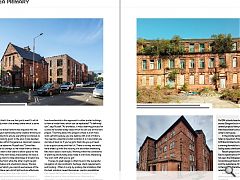

Across Glasgow, historic schools lie abandoned and unloved following the modernisation of the education system, but amid the dereliction and decay several schools stand out as exemplars of the untapped potential bound within their sandstone walls and overgrown playgrounds. The latest of these, Holmlea Primary School in Cathcart, illustrates how such buildings can be readily repurposed for social housing when paired with a sympathetic client and architect.

Home Group Scotland and Anderson Bell + Christie have sensitively transformed this B-listed primary school, restoring the main block and building two complementary red brick buildings without compromising the principal façade. It is an approach that has only been made possible through the intervention of the affordable housing provider, with the private sector failing to come up with a workable solution.

Illustrating the troubled recent history of Holmlea AB+C director Stuart Russell told Urban Realm: “The thing with Holmlea is we’ve been looking at it since 2015 and even before that it was sitting on City Building’s register of sites for sale. The private sector had looked at it but no-one could get it to stack-up, the affordable housing element helped save it and make it work.

“They (Home) saw the opportunity to create something special and partnered up with GHA to do just that. Private developers had been talking about taking the roof off, adding a glass storey and taking it down to the basement, to make it viable all of which would have been detrimental to the history of the building but even in doing that they could not get the numbers to work.” A light touch approach saw AB+C retain as much of the fabric as they could, with only the former gym hall having to be sacrificed for the project to stack up. “Home were as keen as we were to keep the fabric. Because we were converting to homes we couldn’t keep the classrooms as they stood but both main atrium spaces and stairwells have been restored to life as they were. We ended up with a lot of interesting flat types but the classic proportions had to go because they weren’t planned as homes for one but also because the school had fallen into such a state of disrepair.” A greater degree of intervention was required in the interior where internal timber partitions had rotted, illustrating the rapid pace of decline once water seeps in.

Russell said: “When we first got to the building, we were sent photos by City Building and it looked fine, almost like it does right now. Someone had gone in and stripped lead off the roof and it just let the water in and destroyed it. I put my foot through a floor when I visited for the first time and we all just gently backed off.” Faring worst of all was the old gym hall, which was the first to be targeted by lead thieves owing to a lower more accessible roof. Water ingress had caused the floor below to warp. “If the project was going to work that was the sacrifice that had to be made.”

Russell continued: “There was a real danger that the building would have collapsed inside. All the outside walls were 600mm thick and probably provided enough support to do what they needed to do but water had penetrated the wellheads internally and got behind the plaster, tiling and finishes. It was all gone. The only thing we could do was strip it off and we were left with the stone and concrete elements.” Despite these losses the team were determined to salvage as much as they could with features such as balustrades, picture rails, trusses, roof lights and doors all being retained while salvaged red sandstone taken from the demolished sports hall was used for feature walls and pathways within the grounds.

‘Green Peggy’ roof slates were crushed and used as path borders by TGP landscape architects and a statue carved from one of the pillars of the building has also been installed – minimising the quantity of waste material removed. This approach, as well as being respectful of history and the environment also ensured that the sunk cost and carbon embodied by the craftsmanship and high-quality materials, unachievable today, would not go to waste. While this has taken additional effort, Russell is pleased with the results and so to are the people of Cathcart given the rapidity with which the flats were snapped up.

“If you were less keen on retaining the history you could have gutted all the interiors and focussed on facade retention but that wasn’t our ambition and it wasn’t the clients either,” he says. “For all those units we didn’t have to pour any concrete into the ground. In terms of the carbon footprint, it’s a whole lot less because the building already exists.” What may have saved Holmlea is the strength of the site itself, which occupies a significant parcel of land in a desirable tenement neighbourhood. Did the luxury of new build options offset inefficiencies in repurposing the main building? “When we were originally looking at it we thought of putting units in front of the janitor’s house but they compromised the building too much. The feeling was we didn’t want to compromise the historic frontage but we did have space to manoeuvre at the boundary line where the school building meets the tenements. It was about building up the density at that side without taking away from the prominence of the main school building. We didn’t want to come over the eaves line or take anything up too high.

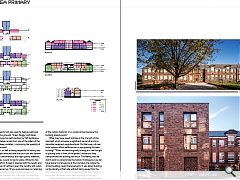

“We tried to leave the gable ends free as best we could with the janitor’s house sitting there as it always has, if you could choose a unit that’s the one that you’d want! It will sit there and do exactly what it has always done which is serve the main school.” Internally a more radical rethink was required with the proportions and layout demanding some creative thinking on the part of the architects to ensure everything functioned as it should as well as looking good. In the end, it was decided to create maisonettes within the generous classroom spaces, invisible to the casual observer.

Russell said: “Some flats hadn’t room for two full storeys so we made them so that as you walk in you go down a few stairs to allow space for the upper floor. Most of the two-storey maisonettes will have a double-height living room to take advantage of at least one of the windows to the front while the other might be split between a kitchen below and a bedroom above. We also put in a mansard roof which you cannot see because of the valley. The flats up there get a lot of light and are effectively new build elements away from the main school.” It is the two newly revitalised atriums which Russell is most pleased with, both of which have been restored to their former glory as fitting communal spaces. The key question is how transferrable is this approach to other similar buildings, is there a model here, which can be replicated? “It definitely can”, says Russell.

“As architects, it was a learning process for us and we’ve taken away ideas which we can use on the next project. The thing about this project is there is a lot more work upfront because you are dealing with a bit of history. You need to understand what condition it is in and what you can take it back to. If you’ve got a fresh site you just need to do a quick survey and that’s it. There is no way we would have ended up with this housing mix and these interesting flats had it been a new build. Working within the constraints of planning and funding does make it a lot more interesting. You work with what you’ve got.” The key to great design is often found in the successful navigation of site constraints; heritage, client requirements and funding. Often it is only by probing the limitations that the best solutions reveal themselves, guiding possibilities that cannot be found on a blank piece of paper. In a city where the path of least resistance too often leads to demolition, it is heartening that projects such as Holmlea can offer a different path.

|

|