Chernobyl: Fallout

20 Apr 2021

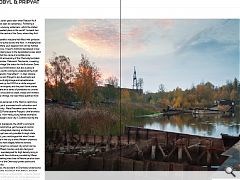

To coincide with Ukraine’s bid for UNESCO World Heritage status for Chernobyl and Pripyat - and the 35th anniversary of the world’s worst nuclear disaster, Mark Chalmers appraises how Soviet architecture has fared against the ravages of time, radiation & neglect. As nature reclaims the land what has the zone left behind? Photography by Paul Hill-Gibbins, chernobylgallery.com

Two hours north of Kiev along an arrow-straight highway, you reach the Zone of Alienation. The minivan draws up at a checkpoint guarded by soldiers in fatigues, armed with geiger counters and Kalashnikovs. Radiation! Danger! No photographs! command the signs. Thirty kilometres short of Chernobyl, the marshland is dotted with triangular red and yellow radiation hazard signs.

These tracts, known in Ukraine as “polesie” or forestland, spread beyond the horizon. After passing through a second checkpoint twenty kilometres further on, the faintest outlines of Pripyat’s high rise blocks and the sarcophagus of Reactor No.4 emerge above the pine trees. During the late 1980’s this was the most radioactive place in the world.

The area became known as the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant Zone of Alienation, the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, or simply the Zone. At its centre lie the ruins of Chernobyl nuclear power plant and city of Pripyat. Paul Hill-Gibbins has visited the Zone several times and acknowledges that it’s easy to be smitten by Chernobyl – “The Zone to me is many things including sombre, peaceful and surprisingly beautiful. The first time I wandered alone through its streets and buildings was a unique feeling and something I’ve craved many times since.” The images on his website, chernobylgallery.com, demonstrate why Chernobyl and Pripyat are so compelling.

“At the edge of the city thick undergrowth and trees frequently obscure the buildings and often the only reminder that you’re walking on what was once a busy road is a kerb or periodic streetlight.” Pripyat is an entire Modernist city abandoned to nature. In the early hours of 26th April 1986, No.4 reactor at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant overheated during a safety test. A power surge inside the core led to explosions which blew the 2000 ton concrete lid off the nuclear reactor, and the resulting fire spread a cloud of radionuclides across Ukraine and Belarus then Poland, Germany and Sweden. Millions of people owe their lives to the Liquidators: the helicopter pilots, robot operators and firefighters who fought to staunch the reactor’s overheating core with sand, dolomite, boron and lead. Many would succumb to radiation sickness, but without their efforts the reactor would have melted down completely. A memorial, known as the “Monument to Those Who Saved the World” stands in a quiet corner of Chernobyl. Its name is more than rhetorical.

Thirty-five years later, Pripyat seems like a modern Pompeii: a ruined, irradiated city which has been given up by people. But the Zone of Alienation around Chernobyl is anything but abandoned. Every day, thousands travel into the Zone to carry on the process of remediating the wrecked power plant. Ecologists study flora and fauna inside the Zone, such as the radiotrophic fungi which seemingly thrive inside the ruins of Reactor No.4, where a few minutes’ exposure would kill a human. Each year, thousands more curious visitors also make the trip: many are what you might call atomic tourists, inspired by the recent HBO television series “Chernobyl” and a video game named S.T.A.L.K.E.R. However, rather than tourists, or the nuclear plant workers and Communist Party officials who figure in the television series, this article focuses on two people: Maria Protsenko, Pripyat’s chief architect who supervised the city’s expansion; and Andrei Tarkovsky, the film-maker who many believe foretold the accident and its aftermath in his film “Stalker”.

In September 1966, the USSR launched a 10-year plan to develop a nuclear power station in the Ukrainian SSR, to provide power to a population of 50 million. Dotted across the former USSR are many “monogorod” or single industry cities, such as Magnitogorsk in the Urals which was built around the iron and steel industry. In 1970, Pripyat was founded two kilometres from Chernobyl as the ninth Atomgrad, or atomic city, in the USSR. Maria Protsenko became chief architect of the City of Pripyat at the remarkably young age of 33. Born to Sino-Russian parents, she was brought up in Kazakhstan and studied architecture at the Institute of Roads and Transport in Ust-Kamenogorsk. By 1986 she had been Pripyat’s chief architect for seven years, and had already expanded the city from two “mikrorayons” (micro-districts) to four, and was in the process of planning Pripyat’s new sixth district on reclaimed land beside the Pripyat River.

Each mikrorayon is a neighbourhood which typically houses between 8,000 and 12,000 people in a mixture of slab blocks and high rise towers ranging from five to 16 storeys. Pripyat already had a population of 50,000, living in 13,000 apartments spread across 160 blocks. The expansion would have ultimately taken the city to 200,000 people, many of whom would work in the Chernobyl Two power plant whose No.5 and 6 Reactors were already under construction.

As in the West, mass housing in the Eastern Bloc during the 1960’s and 70’s consisted of large panel systems fabricated from precast concrete. The decision to adopt an industrialised system was made by Comecon, which decreed that buildings from the Elbe to Vladivostok would be constructed on identical lines. They were based, like virtually all large panel systems, on a common ancestor – the Larsen-Neilsen system – and consist of sandwich panels with a load-bearing concrete inner leaf, a layer of insulation and a concrete outer leaf. The housing blocks were nicknamed “Khrushchyovska” as they were developed during the 1960’s while Nikita Khrushchev was in power. They began as five storey walk-ups with precast wall panels and pre-plumbed bathroom pods, and by the 1970’s the system had developed into the eight storey slab blocks typical of Pripyat. While the apartment blocks were system-built from precast panels, many of Pripyat’s public buildings such as the “Energetik” Palace of Culture, Hotel Polyssia and City Hall were in-situ adaptations of standard designs constructed throughout the USSR.

However, Maria Protsenko personally checked and signed off the quality of concrete work, and detailed parquet flooring, marble cladding and coloured mosaics to offer them a little more craftsmanship and colour. The power plant workers were amongst a proletarian élite, if that isn’t a contradiction in terms and facilities in Pripyat such as the Avangard sports stadium, Raduga (Rainbow) department store, Lazurny (Azure) swimming pool and Kinoteatr Prometey (Prometheus cinema) provided a standard of living which was better than that of a typical Soviet city. Something else which set Pripyat apart was how Protsenko integrated buildings into their setting. The high density of the mikrorayons was deliberate: it freed up space for parkland, sports facilities and playgrounds. Even before it was abandoned, the city was much greener than other monogorods.

Today Pripyat’s tree-lined avenues are overgrown, but apricot trees bloom in the overgrown gardens while bison, boars and wolves roam through the city. The most remarkable part of Maria Protsenko’s life is that 36 hours after the reactor exploded, she took personal charge of evacuating Pripyat. As the city’s masterplanner, she had access to city maps which were vital in ensuring the process was fast and thorough. When the order came, 1100 buses arrived on Lenina Prospekt and according to Adam Higginbotham’s book, “Midnight at Chernobyl”, Protsenko even rode around Pripyat in the last bus to collect the final stragglers. It took time for the enormity of what happened at Reactor 4 to sink in, but soon afterwards we began to search for reference points. There had been previous atomic disasters, at Windscale in Cumbria and Three Mile Island on the east coast of the US, but uncanny parallels lay in a film made by a Soviet auteur seven years earlier. With hindsight, Andrei Tarkovsky’s “Stalker” seems like a premonition of the accident. It portrays a world destroyed by Man which has begun regenerating itself.

The strangely mutated plants and insects which grew back in the Zone of Exclusion around Chernobyl were foreseen by Tarkovsky as the Zona, a temperate jungle of plants into which only stalkers go. A stalker, in the original John McNab sense of the word, is a guide who leads people through the wilderness. Tarkovsky’s film was based on “Roadside Picnic”, a novel by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky which features a young rebel who hikes covertly into the Zona to collect the mysterious artefacts which alien visitors have left strewn around, almost like litter abandoned after a picnic. The film’s point of departure was “a breakdown at the fourth bunker”; seven years later when Reactor No.4 overheated, that was seen as a prophecy. Following a journey through an uncanny wilderness, which the stalker describes as “the quietest place in the world”, he leads two fellow travellers to the centre of the Zona, where they find the Room. The Room is a derelict industrial hall filled with pollution which flows like sand dunes across the floor.

In metaphysical terms, it’s a place where your deepest wish can be fulfilled – but at a terrible price. It seems mankind developed a new reticence about nuclear power in the devastated power plant at Chernobyl, and that too came at a terrible price. Now, on the 35th anniversary of the Chernobyl accident, Ukraine’s culture minister, Oleksandr Tkachenko, is seeking UNESCO World Heritage Site status for the Exclusion Zone: “This is not only a tourist attraction, but also a place of memory where it is worth coming to understand the truth about the disaster and its ‘final effect’”. In that, Ukraine would like Chernobyl and Pripyat to join Auschwitz and Hiroshima as a place of pilgrimage and remembrance. Churchill summed up the USSR as a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, and the post-Soviet states still intrigue us. There are a series of paradoxes to unravel. Nuclear power was once seen as clean, cheap and limitless: in the age of climate change, we need those qualities more than ever before.

Communism was perceived in the West as restrictive of personal liberty, yet it promoted multi-culturalism and equality of opportunity. Maria Protsenko came from the very edge of the USSR and became Pripyat’s chief architect whilst in her thirties. How many young female architects got the chance to design a new city in Scotland during the 1970’s? From a Western standpoint, the USSR’s command economy seemed constrictive, yet the level of control required to achieve integrated planning, architecture and delivery at Pripyat was only possible through state intervention. In fact, you could argue that what Soviet-era design achieved in the city is what Western urbanists endlessly pursue, but have largely failed to achieve. For example, Pripyat is a compact city which can be crossed on foot in fifteen minutes, and also had good public transport. It was designed for high density living in apartment blocks, with free childcare provided by fifteen kindergartens. Its setting was close to Nature yet also close to work, in the form of the Chernobyl power plants and nearby Jupiter factory.

In a final paradox, the accident at Chernobyl underscores both our unsustainable disconnect from Nature, and how Nature takes back what we’ve devastated. Likewise, Pripyat demonstrates how the Modernist city can be destroyed, yet simultaneously survive to capture our imagination in ways that its architect never envisaged.

|

|