A Balkan Journey: Peripheral Vision

20 Apr 2021

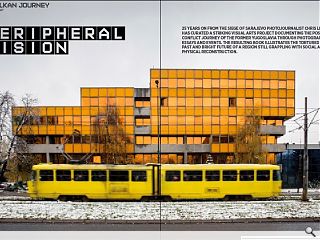

25 years on from the siege of Sarajevo photojournalist Chris Leslie has curated a striking visual arts project documenting the post-conflict journey of the former Yugoslavia through photographs, essays and events. The resulting book illustrates the tortured past and bright future of a region still grappling with social and physical reconstruction.

A quarter-century in the making, Chris Leslie’s photographic record of the Balkans ranks as one of the most ambitious art projects of recent years, an outcome impossible to predict when Leslie took his first faltering steps into a literal and cultural minefield in 1996. As a naive 22-year old who hadn’t so much as held a camera Leslie went on to document one of the most traumatic episodes in recent European history. 2021 marks 25 years since the end of the siege of Sarajevo and Leslie has marked those fateful days with A Balkan Journey, a photo book that documents the aftermath of a brutal war while giving hope to a new generation by charting an impressive period of reconstruction.

Recalling his first foray from one corner of Europe to another Leslie told Urban Realm: “I was a young 22-year-old lad from Airdrie, recently graduated in psychology with politics - one of those degrees you do when you don’t know what you want to do when you grow up. I did my dissertation on the former Yugoslavia and I thought, can I get out there?” Seeking voluntary work in the region Leslie faced the small problem of a barren CV but this proved no barrier to youthful determination. “I had nothing to put down on the skills and interests section”, recalled Leslie, “so I put down photography - but I’d never taken a picture.”

Armed only with boundless enthusiasm and an itch to travel, Leslie duly taught himself the basics of photography over a panicked three-month crash course before setting off in August 1996 to teach photography to local children in the town of Pakrac, Croatia. Recalling with fondness a more innocent age which was to propel Leslie into a life of photography and documentary making, Leslie said: “It was the last time I got to experience everything around me without feeling the need to capture and Instagram everything. Of the photographs I took at that time half were destroyed or lost and the ones I did develop I thought were shit, so I discounted them.

Now, 25 years later, going back to those images you see a place that no longer exists but there was no preconceived notion of what photography should be.” Illustrating the depth of animosity that had developed between different cultural groups Leslie recounts how an early cultural faux pas opened his eyes to the entrenched divisions. “I was given a Yugoslavian phrasebook but it was already out of date because you then had the Croatian, Serbian and Bosnian languages - they were the same language, each with a handful of particular words. In the town of Karpach there was a bakery and I went out to buy some bread and used the Yugoslavian word ‘kleb’, but the Croatian word for bread was ‘hleb’ and the shopkeeper refused to serve me. Such was the intolerance.” From this unpromising start, a love affair blossomed between the photographer and his adopted home with frequent visits over the ensuing decades resulting in a wealth of material which in time would become ‘A Balkan Journey’.

“I’ve been back to Sarajevo about 15 times over the past 25 years and collected a jumbled mess of material,” notes Leslie, conceding that there was “no consistency or coherent thought of how it could come together as a book.” Despite this lack of purpose, it soon became apparent that the archive represented a priceless record of a period that is now more relevant than ever. It establishes a tangible link to a past many would rather forget but has an incalculable inherent value that was not at first appreciated. Over time the mundane can become exotic and Leslie is keen to bring this uncomfortable history to life for western audiences by showing the true nature of the conflict through images and essays by John McDougall which dispel lazy misconceptions about the war. Leslie said: “This was our war, on our continent and in our time. In the 1990s there was a prevailing interpretation peddled by Western politicians and media that this was a war of ancient ethnic hatred. That’s the line that suited us not to get involved but it was far from the truth.

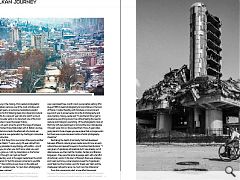

This was a deliberate and planned genocidal campaign, it was never a civil war. “It taught me how easily these things can happen anywhere. The deliberate urbicide of Sarajevo and other towns and cities was deliberate and endorsed by state-controlled media. People never dreamed the war would reach Sarajevo. Not with a highly educated and secular population. Not in a modern European city. In those days there were just a handful of channels, nowadays we have thousands of channels spreading misinformation and hatred. In journalism it taught us not just to report anymore – you can’t be subjective when one side is slaughtering the other – you need to call it out.” Inevitably much of a Balkan Journey depicts scenes of destruction but these same images also play a key role in the healing process serving not just as a record of a fading past but by providing valuable evidence for prosecuting war criminals.

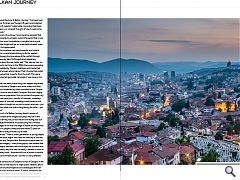

Those early images of the war and siege in Bosnia are the photos that still play out in people’s heads and the media 25 years on and Leslie is keen to bring the story up to date. Leslie continued: “There is a new generation of young people in Bosnia and the wider region who have no memory of this war, nor do they want one. People within Bosnia and outside need to be looking at new imagery – new photographs, new realities that show how the region has been rebuilt and open for business and investment. In many ways this was the reality I wanted to show in this Balkan Journey book – there are still a lot of issues to resolve with the politics and infrastructure – but this is a very different region.”

Likening the turnaround of Sarajevo to that of Glasgow in the 1980s Leslie points to the need for a major public relations effort to shatter the sort of preconceptions and stereotypes that can linger in the face of an evolving reality. “It needs something like the Glasgow Smiles Better campaign of the eighties,” explains Leslie. “You need a strapline to tell the citizens how good their city is. For some wee woman in Easterhouse ‘Scotland with Style’ doesn’t work, but it works for tourists coming to shop in Buchanan Street and hang out in the Merchant City.” What has surprised Leslie most over the past two and a half decades of tireless record keeping? “The most surprising thing I have witnessed is the level to which Sarajevo (the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina) has been able to rebuild from the ashes. Although Sarajevo is a name that might seem inextricably linked to war and tragedy, the passing of 25 years has done much to heal this remarkable and resilient city, and tourism is now sharply on the rise. Sarajevo is beautiful and a city of architectural contrasts, religions and beliefs - a city where east meets west, often called the Jerusalem of Europe.”

One of the first buildings Leslie visited in 1996 also made one of the biggest impressions, the iconic National Library which was subsequently destroyed over two days of deliberate shelling in August 1992 with the loss of 90% of the collection. Only the walls and pillars survived. Now following extensive restoration, it once again stands proud as Sarajevo City Hall and a symbol of the city’s reconstruction. Nowhere is this renewal more apparent than the UNITIC twin towers designed by Ivan Štraus, totemic twin towers in the heart of the city which once served as a symbol of destruction after being heavily shelled and standing as a constant reminder of home for Leslie who had been fond of the Whitevale and Bluevale flats on the Gallowgate. “People in Sarajevo are immensely proud to have survived despite being bombed continuously. People knew what they were fighting for”, notes Leslie.

“People need these images but you also have to be able to move on. The younger generation shouldn’t have to carry the war as baggage.” There’s a rawness and hard reality to Leslie’s images which convey the harsh reality of life in a broken country that to this day faces considerable social challenges. “I was in Sarajevo in 2018 and there were hundreds of refugees and migrants queuing for food outside a mosque, a lot of sleeping in the streets, in camps (if they were lucky) and empty destroyed buildings from the war. Behind these changes lies a considerable irony in that just as Croatia has taken the symbolic and positive step of joining the EU so has the United Kingdom departed. “Security, transparency and investment is key to Balkan stability,” notes Leslie. “It’s surprising that the journey got to this point because 25 years ago, whilst living in the ruins of a small war-torn town in Croatia, the idea of being part of Europe and at peace seemed impossible. And ironically – as Croatia is now a member of the EU, the UK has now left.

It’s a sign of the topsy turvy world we live in and an important reminder of how populist politicians and media can alter everything.” Those who don’t learn the lessons of history are doomed to repeat them and Leslie’s timely commemoration of a shocking period in history reminds us that the unthinkable can and does happen, a message which is as relevant today as it was 25 years ago. Limited copies of A Balkan Journey are available at www.balkanjourney.com/the-book/

|

|