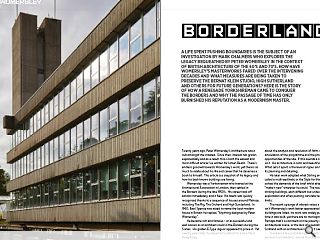

Peter Womersley:Borderlands

18 Jan 2021

A life spent pushing boundaries is the subject of an investigation by Mark Chalmers who explores the legacy bequeathed by Peter Womersley in the context of British architecture of the 60’s and 70’s. How have Womersley’s masterworks fared over the intervening decades and what measures are being taken to preserve the Bernat Klein Studio, High Sutherland and others for future generations? Here is the story of how a renegade Yorkshireman came to conquer the borders and why the passage of time has only burnished his reputation as a modernism master.

Twenty years ago, Peter Womersley’s architecture was a cult amongst the initiated. Since then, interest has grown exponentially and as a result, this is both the easiest and most difficult article I’ve written for Urban Realm. There’s endless goodwill towards Womersley’s work; yet there’s so much to relate about his life and career that he deserves a book to himself. This article is a snapshot of his legacy and how his best-known buildings are faring.

Womersley was a Yorkshireman who trained at the Architectural Association in London, then settled in the Borders during the late 1950’s. His career took off almost immediately, and it flew. His talent was quickly recognised thanks to a sequence of houses around Melrose, including The Rig, The Orchard and High Sunderland. In 1960, Basil Spence was asked to name the best modern house in Britain: he replied, “Anything designed by Peter Womersley”. He became rich and famous – or as successful and well-known as an architect could in the Borders during the Sixties. His golden E-Type Jaguar appeared to prove it. Yet twenty years later, he departed Scotland for a new life in Hong Kong. Womersley’s early work is pure Modernism. It’s about the analysis and resolution of form, driven by the articulation of the programme and the problems and opportunities of the site. If this sounds a bit daunting, it isn’t. His architecture is calm and beautifully-resolved. What sets it apart is the level of rigour and sophistication in its planning and detailing. His later work adopted what Stirling and Gowan called a multi-aesthetic or the Style for the Job, which solved the demands of the brief whilst attempting to “make it new” wherever he could.

The result is a series of striking buildings, each different but united by a sense of exploration and often pushing concrete technology to its limits. The recent upsurge of interest raises a question: why isn’t Womersley’s work better appreciated? Several of his buildings are listed, his work was widely published at the time it was built, yet there are no monographs about him. Perhaps that’s a comment on the poverty of the British architectural scene, or the lack of a publishing house in Scotland with an architecture list, but it seems an oversight. There are a few possible explanations. Womersley worked in a hinterland, remote from Edinburgh and Glasgow where the architectural action supposedly happens.

The Borders is one of many areas which go missing in architectural history. He kept his practice small, so that he could spend time designing rather than administrating – yet his oeuvre is too diverse to be pigeonholed. He built in city streets and interiors and in the countryside – but that could also be seen as a strength. So the question remains in the air. Womersley’s first commission was Farnley Hey, a one-off house in Yorkshire for his brother. His second was High Sunderland, a house for the emigré textile designer Bernat Klein. The story of how Klein and Womersley met and became close friends is told beautifully in Shelley Klein’s recently-published book, “The See-Through House”, and the importance of that relationship is axiomatic.

The Yorkshireman influenced by Californian design worked with the Serbian textile designer to create two of the best post-War buildings in Scotland. High Sunderland is a single-storey, glazed box set on a wooded hillside above the Ettrick Water. Its sophisticated free plan with inter-penetrating courtyard and car port was inspired by the Case Study Houses in post-war America, yet perhaps with Klein’s influence, an exercise in the eight foot grid was softened by panels of colour and exotic hardwoods such as obeche and idigbo. Even this early in his career, Womersley pushed things as far as he could, and occasionally beyond. Bernat Klein reportedly said, “Flat roofs always have problems in a rainy climate.

Today I would opt for a sloped roof, albeit as a disguised one. And I would still go for underfloor heating but not a system as expensive as the one we have.” Womersley was born at the wrong time. Fifty years on, with triple glazing and single-ply roofing, he could have achieved the same building without ruinous energy bills. Meanwhile, Loader Monteith Architects is currently finishing off conservation work on behalf of High Sunderland’s new owners. Speaking to Matt Loader, the project began as a restoration after a fire in the main space, but has also entailed working out how to insulate, install heat pumps and generally improve the environmental performance of the house. Womersley regularly joined the Klein family for Sunday lunch at High Sunderland, and fifteen years later, Bernat Klein commissioned a new studio from him.

It’s best appreciated from the cover of Peter Willis’s book, “New Architecture in Scotland”. It was new, then, sitting bright in the winter sunshine with Klein’s paintings and polychrome textiles glowing. On an autumn day in 2020, silver birch trunks threw shadows across the dirty glass and the studio looked rather forlorn, with an empty interior and smashed doors. The studio is an exercise in balance, its decks cantilevered from the stair core and poised over a brick plinth. An architectural puritan would have used in-situ concrete throughout as a universal material, but Womersley realised that the best expression of its concrete-ness would be achieved using white precast cladding. He used precast in the same way that Mies used I-beams on the face of the Seagram Building: to represent the spirit of the material, rather than the load-bearing truth. The studio fell out of use a few years ago, then Studio DuB won Listed Building Consent for its refurbishment into two apartments.

However, a burst water pipe halted renovations and since then the studio has lain unused. Brian Robertson of the Zembla Gallery in Hawick is a fan. He told me, “I think that Womersley should be better known and his buildings better recognised and cherished. The Klein studio is a national disgrace at the moment. It brings shame on our small country, but we have previous, after all…”. Zembla Gallery hopes to run an exhibition of artwork inspired by Womersley’s architecture some time during 2021, drawn from a wide array of admirers. Speaking afterwards to Gordon Duffy of Studio DuB, “The Studio was the only Womersley listed building in Scotland (even then, only in 1994) and I nominated a number of his buildings including the stadium in 2006 which triggered a review of his oeuvre. Historic Scotland missed an opportunity to list the Port Murray house at the time before the application for demolition. External modifications had been made, but it was totally intact internally.” The loss of that house, near Maidens in Ayrshire, is a warning about Womersley’s legacy. The former Roxburgh County Council buildings at Newtown St Boswells have a happier story. The racetrack-plan office block with its soaring tower is still well used, and as Paul Stallan of Stallan-Brand told me, “Together with Graven we have been advising Scottish Borders Council on their HQ.

Essentially we are attempting to purge the building of accretions to find its essential diagram. The ideal scenario would be decant and undertake a major de-furbishment of the entire complex, unfortunately this has not been possible as the building is still so intensively used.” De-furbishment, the skilful conservation of Modernist buildings by removing half a century’s worth of alterations is also being pursued at one of the best-known Womersley buildings, the stand at Gala Fairydean Rovers FC in Galashiels. The cantilevers and backspans of the canopy are elemental forms – and if you can hear an echo of the Kingsgate Footbridge in Durham, that’s because Ove Arup engineered them both. During a Zoom call with Jim Grimley of Reiach and Hall, I discovered that the initial conservation project will deal with repairs to the decaying concrete and steel reinforcement, but beyond that it’s hoped to strip away decades of clutter – such as the mock-Tudor timbers on the bar ceiling which would have horrified Womersley.

During training, doctors are taught that, “When you hear the sound of hooves, think horses not zebras”, meaning think firstly of common conditions rather imagining you’ve diagnosed a rare illness. All of Womersley’s healthcare buildings, but especially the Nuffield Transplantation Unit at Edinburgh’s Western General, are zebras. On first acquaintance the Nuffield Unit seems like a formworker’s nightmare, but look more closely and the rhythms and ordering principles are as sophisticated as Jørn Utzon’s at Bagsværd Church. In an address to the RIBA in 1968, Womersley himself said, “This building has been dismissed, I know, as a piece of sculpture, not architecture. I don’t see why a building should not be both.” He explained that he strove, “To experiment aesthetically, producing at the same time a building which stands up to both gravity and weather, and satisfies the client in use and as an investment,” and summed up, “My approach to architecture is relatively simple: I try and give delight.” A different side of Womersley manifested itself at the Edenside GP Practice in Kelso. He evolved a modern Scottish language, with consulting rooms contained inside the doocot curves which also delighted Mackintosh and Lorimer.

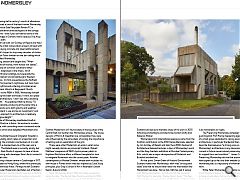

By contrast, the Boilerhouse at Dingleton Hospital is a much plainer building which relies on proportion and surface modelling: the prismatic coal bunkers sit in a tall, narrow tower with a stepped lean-to at the rear, and a soaring chimney. The Boilerhouse is currently empty, but unlike the Bernat Klein Studio it appears to have a future: Studio DuB is working with developer New Life to convert it into five residential units. After completing a leisure centre in Coatbridge in 1977, Womersley relocated to Hong Kong, where he’d previously refurbished the Peninsula Hotel. Perhaps he left Scotland because his particular Modernism had fallen out of fashion – but by then, the Borders textile industry was also in decline, and his struggle and ultimate failure to realise a scheme for Edinburgh College of Art may also have contributed. He left a few things behind. His work proves that Scottish Modernism isn’t found solely in the big cities of the Central Belt; but neither was Womersley unique.

The house designs of Morris & Steedman are comparable: they were also influenced by the same ideas of zoning, the importance of setting and an exploration of the grid. There were other Modernists at work in what some might casually dismiss as provincial Scotland. Robert Matthew’s sequence of 1960’s hydro-power plants in Highland Perthshire offers a different template for how to integrate Modernism into the countryside. Another contemporary is Michael Shewan, whose work includes his own house in Forres which was also inspired by Case Study principles, plus Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen (Urban Realm, Autumn 2014). Peter Womersley died in 1993 and sadly recognition came too late. The Bernat Klein Studio was listed in 1994 by Historic Scotland, following which DoCoMoMo Scotland took a Womersley study tour in 2004, then Historic Scotland carried out a thematic study of his work in 2007, following prompting by architects like Gordon Duffy and Rebecca Wober. Womersley’s first international exposure came from the Scottish contribution to the 2014 Venice Biennale, selected by Jim Grimley of Reiach and Hall, then 2016’s Festival of Architecture featured lectures, a tour of Womersley’s work and the Grey Gardens exhibition at Dundee Contemporary Arts, which was a major retrospective of Modernist and Brutalist architecture. At that point, Simon Green of Historic Environment Scotland noted that Womersley’s work was “an acquired taste” and that he would never reach the mainstream like Mackintosh has done. Not so fast. HES has got it wrong with Womersley before – by failing to list the house at Port Murray, for example. Shelley Klein’s book, “The See-Through House”, was selected as BBC Radio 4’s Book of the Week in 2020, which for a title about Modernist architecture is as mainstream as it gets.

The Preserving Womersley campaign was set up to guard against Port Murray happening again. It consists of a small group dedicated to raising awareness of his architecture, in particular the Bernat Klein Studio. They describe themselves as “a strong voice on behalf of Womersley’s architecture in any discussions with the current or future owners about preserving the Studio in its original form and condition.” James Colledge from Preserving Womersley told me that around 350 people have signed up so far, and their website (preserving-womersley.net) is a repository of information about his work. While Peter Womersley’s reputation isn’t in any doubt, his architectural legacy is. Although it would be fitting to have a book about him on the Scottish architectural bookshelf, it would be even better if that recognition was translated into respect for all his remaining work.

|

|