Linocut Art: On a Roll

21 Jul 2020

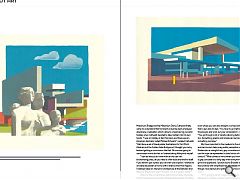

The art of linocut printmaking has long found favour among artists and its idealised designs offer a ready made canvas to showcase architecture in a new light. Urban Realm spoke with Paul Catherall to explore how the medium is shifting attitudes toward Brutalism.

Modernist architecture is being shown in a new light at the hands of artist Paul Catherall. A champion of both the medium and his home town of Coventry Catherall combines the two with uniquely stylised results.

The freelance artist is author of an exhibition of architectural prints documenting Coventry and London, now delayed to the summer, Catherall has deployed his twin passions from his home studio to great effect. Marrying drawing, carving and printing the technique straddles the boundary between art and architecture, but are all creative industries cut from the same cloth?

Addressing Urban Realm Catherall said: “I trained to be an illustrator but when I was at college, I sketched people. It’s a bit ironic that what I thought I was good at and what I wanted to do was quick reportage style sketching, almost like the courtroom drawings you see on the news. Years ago I saw a Sunday supplement article on war artists, not because I fancied going to war but because they followed troops and sketched. I spent 78 years trying to be a figurative illustrator after graduating and I tried to fudge the sketch life drawing style into an illustration style and I came to a tipping point where I thought I’m not loving what I’m doing.”

Inspired by the dawn of a new millennium and a spate of grandiose architecture in London such as The Tate Modern, the Millennium Bridge and the Millennium Dome Catherall finally came to understand that his talents would be best employed elsewhere, a realisation which came to a head during a pivotal holiday when Catherall decided to take matters into his own hands. “I was on holiday in San Francisco and there was an American illustrator called Michael Schwarb,” recalled Catherall. “He’d done a set of travel poster illustrations for Fort Point, Alcatraz and the Golden Gate Bridge and I thought you lucky bastard getting a commission like that. No one was going to commission me to do that so I started doing little prints myself.

“I can do linocuts at home with an old cast iron bookbinding press, all you need is a few tools and the lino itself. If you haven’t got a press you can even use a spoon. I wanted to emulate old posters at home with a theme other than figures. I’d always taken an interest in architecture at the Barbican and National Theatre but hadn’t thought of it as a subject matter.”

Drawn to the concentration, planning and sheer physicality of the manufacturing process Catherall distinguishes illustrative work where you can dive straight in armed with nothing more than a pen and an idea. “You have to go methodically through the process and work out your composition”, notes Catherall. “You go through a lot of careful planning before carving out the lino. Something graphic and simple can be harder to do than something complex.”

But how important is the medium to the ultimate message and can linocuts help sway public perception of Brutalism and Modernism as straight lines, grey concrete and decay? How can the style be represented in bold blocks of clean primary colours? “What comes to mind when you think of Brutalism is grey concrete on a rainy day when everything looks a bit grim and oppressive. I picture iconic Brutalist buildings in the sunshine with simplified lines translated into blocks, even though I love texture and grittiness. The mood is clear in my mind.

“If I’m going to do an image I always try to take and reference my photos. I always wait for strong light in the early morning or late evening to get those strong shadows. Linoleum translates those clean lines directly, it’s a semi-abstraction.”

In communicating architecture to the public, does Catherall find Brutalism a tough sell? Can such work serve as a bridge between the professions? “I’m probably part of that whole generation who grew up with Modernism forming part of your childhood, it becomes embedded in your psyche a bit and you appreciate it in some way. It reminds you of your childhood and upbringing and some people become quite nostalgic about it because it’s been around for so long. Like mid-century furniture and design which has been back in vogue, Brutalism is tied in with that in a way that I see elements of new architecture taking large open spaces that are to be used rather than just looked at from a distance. The National Theatre was designed for people to congregate, it’s not just about what is going on inside.”

Asked whether there was a broader purpose to his art Catherall downplayed any overt narrative but conceded different interpretations may be possible at a subconscious level. “I don’t get involved in campaigns but I am a member of the 20th Century Society. I try and show off these buildings in the light they should be seen and bring out their best aspects. These buildings were made with a sense of optimism and for the general public When the National Theatre was designed there was a lot of thought applied to attract more than just the middle classes, I like to think I’m promoting that. You’ve got to be into the prints that you’re creating or you’re not going to put your heart and soul into it.”

The relatively limited subject matter of Catherall’s work might be seen as a constraint but instead, the artist sees his laser focus as a strength, finding inspiration in endless detail and new angles to give a fresh take on buildings that have been photographed to death. “I’ve always been quite a tunnel vision guy from when I was young painting soldiers for hours on end. Some would probably say it’smundane and boring but I could happily paint the National Theatre all year. I love the method.

“Artistic struggles are all well and good but can be exhausting. While you’re printing it almost always shows you how you could have done things differently. When I’ve done a print I want to do it again in a slightly different way. I could happily live off the Modernist icons of London forever.”

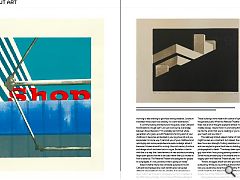

Having been preoccupied with London throughout his working life Catherall has begun to rediscover his upbringing, spurred by the designation of Coventry as UK City of Culture 2021. “My childhood from two to 14 was in Coventry”,says Catherall. “It impacted on me but it’s taken a long time for me to realise it. When I first moved to London finding places like Elephant & Castle shopping centre almost felt homely. I never knew why but now doing all the prints I realise it reminded me of my childhood. I suppose I had a relatively happy childhood. We lived relatively near the centre. My teenage years in the mid-70s to earliest I was a little too young for the specials but I was a little Mod when the Jam were out and that had an impact on my early teenage years. It became ingrained in me.

“It’s only since leaving when people ask where are you from and they say ‘Oh god what a shit hole’. I slowly realised not everywhere was like that. I didn’t go around at the age of 14 admiring the modernist precinct; I just wanted to find a record shop. Now I can see how amazing it would have been in the late sixties when it was newly built and there was less traffic. Elements of it are a modernist masterpiece with beautiful signage and well-detailed shops. The Festival of Britain style has been lost as elements are stripped away and you’re just left with the carcass. Not that I want everything preserved in aspic but all the details which made it so nice, and would now be appreciated, have gone.”

Coventry has proven itself a city which thrives on adversity, and so current events could provide a springboard for change, even with retail being among the hardest hit sectors. Perversely, it is also likely to favour a make do and mend approach to the existing fabric rather than the scorched earth approach favoured during periods of rapid growth. Such a lowering of ambition may ultimately pan out with longer-term incremental improvements, which prove to be far more sustainable.

“The city architects were all left-leaning Labour guys who thought the city should be for the people,” Catherall continued. “What I do fear is the great 50s and 60s architecture not being appreciated and saved in the way that it should be. I get the feeling that’s not part of the remit and everything has got to be brand new. All the forward-thinking, the largest pedestrianised shopping centre in Europe, it’s been forgotten and I fear that isn’t going to be shouted about. I think what did for Coventry was the 70’s when there was no money for upkeep. Everything was just left.”

Catherall believes the pending City of Culture accolade will focus attention on his hometown, thrusting it back into the limelight. “For years I’ve said I’m going to do Coventry but the prints take so long to do, a print is three or four months’ work. If no-one’s going to buy them, I can’t afford to do it.”

If a picture is worth a thousand words then Coventry’s pressing problems may be found in art, bringing colour to a grey place and arresting a gradual decline which can be far more insidious than an abrupt collapse.

|

|