Brick Revival: Material Matters

21 Jul 2020

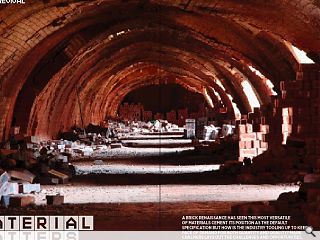

A brick renaissance has seen this most versatile of materials cement its position as the default specification but how is the industry tooling up to keep pace of demand for both quantity and quality? Mark Chalmers lays out the challenges and opportunities.

The late Isi Metzstein of Gillespie, Kidd & Coia once remarked that brickwork is twice handmade: once in the brickmaker’s mould and for a second time when laid by the bricklayer. That’s a rather romantic view of the brickmaking industry, which in the 1960’s could still claim to be a traditional craft, employing time-served brick setters and kiln burners.

Brick making in Scotland has changed radically since then. Even twenty years ago, there were around a dozen operational works. You may remember some of their names: Wemyss Brick in Methil, Bothwell Park Brickworks, the Etna and Mayfield brickworks of GISCOL which became Caradale Brick, Raeburn Brick, Centurion Brick at Cadder and Tannochside, Cruden Bay Brickworks in Aberdeenshire, Cults Brick and also Kirkforthar Brick in Fife, and Inchcoonans in Perthshire which became Errol Brick.

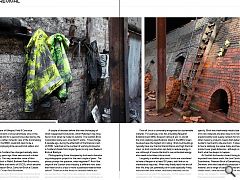

A couple of decades before that was the heyday of small independent brickworks, which Metzstein may have had in mind when he made his remark. The Scottish Brick Corporation alone own once had 17 works. Times change. A decade ago, during the aftermath of the financial crash of 2008, I watched as the number of working brickworks in Scotland shrank from single figures to only one, Raeburn Brick at Blantyre.

Photographing those disappearing brickworks became my photographic project for the next couple of years. The photos prompt the question, what happened? And if the shape of the Scottish brick industry is different now, does that mean brick is a less or more sustainable material than before? There are a few things to consider before you can answer that. There’s the raw material, the production process, how the brick gets to site and how it contributes to a building’s performance.

First off, brick is universally recognised as a sustainable material. For example, brick has a Building Research Establishment (BRE) Ecopoint rating of just 1.1, and all the brick cladding specifications listed in the BRE’s Green Guide achieve the highest (A+) rating. Brick-built buildings typically have low thermal transmittance and high thermal mass, so brick construction can help to reduce energy in use, although of course the brick’s own embodied energy also needs to be taken into account.

Longevity is another plus point: bricks are considered to have a lifespan of at least 150 years, with little or no maintenance required. When they finally reach the end of their life, they can potentially be re-used especially if they were laid with lime mortar, and failing that they can be crushed and recycled for aggregate. In that sense, bricks contribute to the “circular economy”.

However, the catch lies in which particular brick you specify. Brick was traditionally made close to the source of its raw materials and also close to its market. The predominantly local supply network for brick, concrete and other masonry products means that delivery distances from builder’s merchant to site are short. It doesn’t make sense to haul a relatively low value, bulky and heavy commodity product over great distances – although in recent years that’s what has begun to happen.

As Scottish brickworks closed, facing bricks have been imported from down south, the Low Countries and even Scandinavia. Petersen Brick of Sønderborg in southern Denmark, with their beautifully-produced marketing material, and a range of subtly coloured and textured clinker bricks, have become the brick of choice among design-led architects. However, they come at a cost, both financial and environmental.

Transport costs, and the associated CO2 emissions, are now a real issue. Speaking to Michael McGowan, Group Sustainability Manager at Ibstock, the average delivery distance for Ibstock’s bricks is 62 miles. With only one manufacturer left in Scotland, all other brick products come from England, plus a small but growing amount from Europe. Before Covid-19 struck, around 30 to 40 million bricks per month came into the UK from EU and Non-EU countries, against brick production in Britain running at around 160 million, which equates to two billion bricks a year. Anything not manufactured in the UK inevitably has a much higher carbon footprint, which makes it less sustainable.

Making fired bricks is energy intensive: kilns are fired for long periods at around 1000 deg.C. The fuel nowadays is usually natural gas, in the past it was coal. In traditional Scottish brickmaking, the calorific content of oil shale or colliery blaes helped to reduce firing times, although traditional brickworks with coal- and gas oil-fired Hoffman kilns were inefficient and generated more air pollution than their modern cousins.

As an example, Caradale Brick’s Mayfield Brickworks at Carluke was increasingly unusual by the turn of the 21st century in that it made bricks using shale clays recovered by reworking old colliery bings: the shale contributed to a harder and more durable brick. When it was built in the 1950’s, there were a couple of dozen other brickworks within a few miles’ radius, and most of them also used coal and oil shale waste. By the time it closed in 2011, it was the last of its kind.

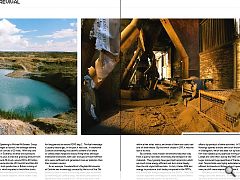

By contrast, most modern brickworks take their clay from a quarry next door, minimising the transport of raw materials. They typically have gas-fired tunnel kilns which are much more energy efficient and burn more cleanly than the old-style Hoffman kilns. In fact, it takes 65% less energy to produce a brick today compared to the 1970’s, and a third less energy compared to the 1990’s. That’s the counter argument to having lots of small, local brickworks dotted around the country as we once did.

In Scotland, the raw material for brickmaking was often a by-product of other activities. In 1988, L.A.W. Holdings opened a brand new brick factory at Tannochside in Uddingston, which was later run by Ibstock Brick. The firm was headed up by opencast mining entrepreneurs Ian Liddell and John Weir: during the 1980’s their opencast at Lugar produced huge quantities of fireclay in addition to the coal. Tannochside was highly automated and was the most efficient brickworks in Britain when it opened: only eight men per shift were required to operate it.

Efficiency is still critical, especially when it comes to energy costs and emissions. As natural gas costs rise and we move away from burning hydrocarbons, the ceramics industry has investigated the electrification of kilns, but electricity costs per kWhr were historically 5.5 times more expensive that gas, and at the moment that figure is around 9 times higher.

The ceramics industry has a sustainability working group looking at alternatives such as renewables, principally the so-called green gases such as syngas and biogas which can be produced on site at brickworks. Long term, the gas network in the UK is aiming to supply 90% low-carbon gases by 2050, and meantime a UK Government project called HYNET hopes to feed 10 to 20% hydrogen into the gas network in certain regions of the UK by 2025.

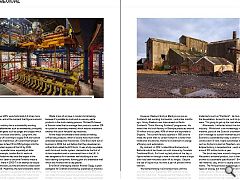

Emissions are a parallel issue, especially at older brickworks. For example, London Brick’s works at Stewartby in Bedfordshire was once the largest in the world. Hanson Brick (later to become Forterra) made a major investment there in 2005-7 in an attempt to reduce sulphur dioxide emissions, but the brickworks closed soon afterwards in 2008. Meantime, the new brickworks which Hanson built at Measham in Leicestershire, on the site of the old Red Bank fireclay factory, can make 100 million bricks a year with a staff of 28. Latterly Stewartby needed 220 people to do the same.

Waste is less of an issue in modern brickmaking, because it’s possible to crush and re-use any waste products in the brick-making process. Michael McGowan of Ibstock noted that on average their products contain 12% re-cycled or secondary material, which reduces waste and extends the use of valuable clay resources.

All the major brickmakers have looked at making unfired clay products, which of course have much lower embodied energy than fired bricks. Errol Brick went out of business in 2008, but just before that they developed an unfired brick called the ECO brick. It was a fully-recyclable earth brick and mortar system, claimed to be the first of its kind manufactured in commercial form in the UK. It was designed to fit in between wall studding as a non load-bearing component, forming part of a breathable wall which was finished with a clay plaster.

Errol Brick’s managing director Andrew Clegg, a great evangelist for Scottish brickmaking, explained on a factory visit I made to Inchcoonans brickworks that the ECO brick was made from post-glacial alluvial clay, sand and sawdust, all taken from local sources. But not even the development of “green” bricks was enough to save Errol Brick.

However, Raeburn Brick at Blantyre survive as Scotland’s last working brickworks – and a few months ago, Jimmy Raeburn was interviewed on Radio Scotland’s “Good Morning Scotland” programme. He noted that his brick factory in Blantyre produces around 18 million bricks a year, 40% of which are exported to England. The current factory opened in 1985 and he made the point that its carbon footprint is lower than traditional brickworks, thanks to investment in energy efficiency and automation.

By contrast, in 2012 I visited Etna Brickworks at Bathville which had been run until closure by Caradale Traditional Brick. As I took my last photo of the day, a figure walked in through a hole in the wall where a large door had been knocked clean off its hinges. Despite the sea of liquid mud, he wore a pair of pristine white trainers.

We started talking: he’d worked here until the brickworks shut in September 2011, and had come back for a last look. He explained that Raeburn Brick had bought up some of Etna’s equipment, such as the pan mills and carousel and also some of Caradale’s trademarks such as “Pentland”. He took a final look at the devastation, turned to me, and his parting words were, “I’m going to get up the road afore I start cryin…”

Afterwards, I reflected about the state of the industry. While brick is an increasingly sustainable material, parts of the Scottish brickmaking industry didn’t manage to sustain themselves profitably. Economic sustainability today is down to the construction of vast, highly automated brick factories such as Forterra’s plant at Measham, and Ibstock Brick’s Eclipse factory in Leicestershire – each of which make around 100 million bricks a year.

The brick may have moved a long way from Isi Metzstein’s artisanal product, but is there a simple answer to sustainable specification? Bricks use a natural raw material, clay, which is usually sourced close to the works. The firing process increasingly uses greener types of energy, but transportation is a major factor. It makes sense to “Buy Local” wherever we can, and if not Scottish brick, then brick sourced from the UK. More exotic products from the Continent may look alluring, but they have a large carbon footprint.

|

|