Charles Jencks: Landed Gent

15 Apr 2020

Renowned theorist Charles Jencks bequeaths a powerful built and written legacy following his passing in October last year. Best known for contributions to journalism, land art and Maggies Centres Jencks is a towering figure who moved mountains to inspire others. Here Mark Chalmers weaves together three strands of a stellar career.

Charles Jencks passed away in October last year. He was one of the best-known figures in architectural criticism and his obituaries covered a career as architectural historian, his role in co-founding the Maggie’s Centres, with a footnote on his landscape art.

In some respects he was a figure out of his time. He lived near Dumfries but cut a dash like a character from F. Scott Fitzgerald in a corduroy suit, floppy hat and silk scarf. His approach to criticism was serious-minded but intellectually playful, and the handful of times I met him and listened to him lecture, I was struck by the intellectual tenacity behind his dapper appearance.

“When I was a young historian studying under Reyner Banham I wrote a paper, ‘History as Myth’, which showed how each successive historian rewrote the script of Modernism by putting back into the story some of what the previous critic had excised, only to perpetuate a new bias of his own.”

That was a prophecy for Jencks’s own career, a knowing wink which acknowledged how the art historical machinery which drives architectural criticism works. The canon of Modernist buildings provides endless opportunities to debate, argue and reframe: to lecture, write papers and publish books. Like Banham, Jencks mastered the rules early and enjoyed playing the game to its conclusion.

Charles Jencks studied under Sigfried Giedion at Harvard Graduate School of Design during the early 1960’s, then Reyner Banham at the Bartlett School of Architecture in London. Jencks went on to teach Rem Koolhaas. The seeds of Jencks’s career lie in challenging the Modernist canon which Giedion helped to establish; the intellectual tools to do so were honed during his time studying under Banham.

Jencks met his future wife Maggie Keswick early in his career: both took a first degree in English, followed by a second in Architecture. Maggie Keswick’s specialism was landscape history and design, and she proved influential in every part of her husband’s life.

In the early 1970’s, Jencks published “Modern Movements in Architecture”, based on his doctoral dissertation written under the supervision of his mentor, Reyner Banham. Like Banham, he was alert to new trends, and he shared his mentor’s enthusiasm for popular culture. The final “s” in Movements was key: Jencks identified six traditions within Modernism and used them to analyse architecture’s pluralism. Modern Movements was also the first time Jencks discussed the architects who would later become “Post-Modernists”.

“Modern Movements in Architecture” went head-to-head with Kenneth Frampton’s “Modern Architecture: A Critical History”. Those were key texts during the 1980’s and 1990’s, both became set books in architecture schools across the world, and years later I listened to both authors lecture. Frampton is laconic and dry, whereas Jencks sparked with ideas and enthusiasms. Later, they were joined by William Curtis’s “Modern Architecture Since 1900”, and those three competing interpretations still fight over the territory of Modernism.

Charles Jencks’s defining book appeared a few years later: “The Language of Post-Modern Architecture” explored a new architectural trend which Jencks named Post-Modernism. Arguably, he served the same role that Giedion had during the rise of Modernism, and Jencks continually refined his analysis through several editions – just as Giedion had through the inclusion of Aalto and Utzon in later editions of “Space, Time and Architecture”.

Architectural history is an eternal work in progress. Each new edition of The Language of Post-Modern Architecture had a new cover which reflected how Post-Modernism had evolved. Jencks’s third chapter expanded over the years to become a canon of Post-Modernism, taking in Robert Venturi, Aldo Rossi, James Stirling, Michael Graves, Hans Hollein and Mario Botta.

But the book isn’t entirely forward-looking. In this manifesto for Post-Modernism, Jencks also marked the death of Modern architecture, which he located precisely on 15th July 1972, the day the Pruitt-Igoe Housing Project in St Louis was demolished. Jencks scrutinised Modernism’s downfall through the lens of Pruitt-Igoe, which he blamed on architectural dogma, formal impoverishment and the abandonment of Modernism’s social aims.

Post-Modernism made Charles Jencks’s name as a critic and polemicist; arguably Charles Jencks made Post-Modernism. Given his closeness to Academy Editions at that time, and his friendships with the key figures in Post-Modernism, you could also say he became a tastemaker.

A few years later, Post-Modern architecture ran out of steam and Jencks shifted his attention to aesthetic theories which dealt with the beginnings of the universe. In 1995, he published a new book, “The Architecture of the Jumping Universe” in which he identified, “An aesthetic of undulating movement, of surprising, billowing crystals, fractured planes, and spiralling growth … a language more in tune with an unfolding, jumping cosmos than the rigid architectures of the past.”

Crucially, Jencks couldn’t make a connection between this new language and the Post-Modernism which he promoted so enthusiastically during the 1980’s. If Giedion remained the high priest of Modernism and Banham kept faith with the machine aesthetic, Jencks gave up his role as the apostle of Post-Modernism rather too quickly and easily.

Many lives reach an inflection point where someone has to decide whether they believe in progress, that things will keep improving and the future will be better than the past (the neophile); or recognising that things are in decline, and life was better in the past (the nostalgic). Jencks was definitely a neophile, always searching for the new thing.

The Jumping Universe showcased the work of Peter Eisenman, Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry and Daniel Libeskind, but its language wasn’t that of architectural criticism. It was an attempt to relate architecture to fractals, complexity theory and quantum physics. Jencks expected us to follow him down the metaphorical rabbit hole where he equated Modernist architecture to Classical physics, while Jumping Universe architecture was analogous with quantum mechanics.

It was heady stuff, yet perhaps the Jumping Universe was too multivalent and pluralistic, even for Jencks. However, cosmogenesis had a side effect for him. It fuelled an interest in large-scale land art which he had the opportunity to explore thanks to his wife Maggie Keswick, whose family estate in Dumfries-shire provided many hectares of opportunity. In the Garden of Cosmic Speculation at Portrack, Jencks made the leap from critic to creator.

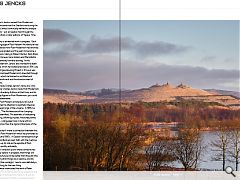

Jencks had assisted Keswick on her book, “The Chinese Garden”, and collaborated with her on landscape designs. His trademarks, some undoubtedly derived from Maggie’s work, became large-scale landforms with sinuous pools of water and paths forming helices and spirals. The garden at Portrack and later the nearby Crawick Multiverse, plus the Ueda Landform at the Museum of Modern Art in Edinburgh, and Jupiter Artland, are all universes in miniature.

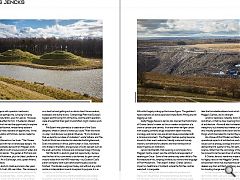

I got an insight into Jencks’s creative process a few years ago, on a visit to Scottish Coal’s HQ near Alloa. The company’s directors were keen to pursue environmental improvement at a vast opencast coal mine outside Kelty. Jencks planned his largest piece of land art, known as Fife Earth or The Scottish World, for the worked-out pit which is a couple of kilometres across.

Jencks’s enthusiasm was infectious, to the extent of putting on a hard hat and getting out on site to direct the excavators, bulldozers and dump trucks. Castlebridge Plant was Europe’s biggest earthmoving firm at the time, and the plant operators were amused that their giant muckshifters might create a work of art.

Fife Eaarth was planned as a celebration of the Scots diaspora, where in Jencks’s words you could “Walk the world in a day”, and discover our global influence. “It is to Scotland that we look for our ideas of civilisation”, wrote Voltaire, and The Scottish World was intended to celebrate the Enlightenment, Scots missionaries in Africa, plant hunters in Asia, merchants who traded in the Baltic, and geniuses of Scots descent such as the poet Lermontov in Russia and composer Grieg in Norway.

Yet Fife Earth is Jencks’s great lost opportunity. Europe was the first of four continents to be formed, its giant conical mound visible from the M90 motorway – but Scottish Coal’s parent company went bust before anything else could be finished. The site lies overgrown today, and without any visitor centre or interpretation boards to explain its purpose, it is as mysterious as the Nazca Lines.

Around the same time, Northumberlandia was created at another opencast coal mine at Cramlington, just outside Newcastle. This time, the landform was the recumbent figure of a woman: a pagan earth-goddess. Northumberlandia plays with scale: miniaturising the landscape of the distant Cheviot Hills whilst hugely scaling up the human figure. The goddess’s head overlooks an active opencast where Banks Mining are still digging up coal.

Sadly Maggie Keswick-Jencks also inspired the third strand of Charles Jencks’s career, as the co-creator and patron of a chain of cancer-care centres. In an era when we fight cancer with surgery, powerful drugs and proton beam machines, oncology and cancer care are almost always associated with a clinical environment. The Maggie’s Centres quickly became known for their warm welcome, friendly scale and homely interiors, somewhere for patients and their families which doesn’t feel like an institution.

Jencks told the BBC that receiving a commission for a Maggie’s Centre project was the architectural equivalent of receiving an Oscar. Some of the centres may owe a little to The Architecture of the Jumping Universe; but none to the language of Post-Modernism. That doesn’t matter: Charles Jencks’s impact on healthcare in Scotland, where the first few centres were built, is inarguable.

Charles Jencks’s life demonstrates that architectural theory isn’t the product of impersonal forces, but the work of individuals, many of whom were linked by teacher/ pupil/ mentor relationships. In fact, the succession through Giedion, Banham, Jencks and Koolhaas connects some of the 20th Century’s most influential theorists. Those connections, and later the formidable address book which he drew upon for the Maggie’s Centres, are his strength.

Jencks’s weakness, noted by Aaron Betsky, Elie Haddad and others, is that he drew meaning from the appearance of architecture. Above all else, he treated buildings as visual metaphors, but showed less interest in plan and programme, and virtually ignored construction and technology – the very things which fascinated his mentor Reyner Banham.

His critique of Post Modern architecture misses the operational aspects of architecture, and completely ignores issues such as energy, ecology and environment which have defined the first quarter of the 21st century. Environmental science, rather than the cosmology of the Jumping Universe, has proved to be the real driver of architecture in recent years.

If Charles Jencks’s name was made by Post-Modernism, his legacy rests on the Maggie’s Centres. They are a lasting achievement which has touched thousands of lives in a much deeper way than architectural theory ever could. But how will his standing change over time?

As the composer Philip Glass noted about reputation, “I don’t know what’s going to happen in ten years. We don’t even get to know what’s going to happen after someone dies. We need to wait until everyone who knew them is dead, too.” It will be fascinating to see what future critics make of Jencks, even as they rewrite the history which he first set down.

|

|