The Phoenix Project: Human Habitat

15 Apr 2020

Tom Morton, director at Arc Achitects, believes resident-run communities can help mend a broken housing model, even as multiple crises threaten to engulf us. Amid the chaos Inverkeithing has emerged as an unlikely ground zero for a bold new beginning.

We live in a time of crisis. Even before Coronavirus and Brexit, the urban realm was struggling to respond effectively to a housing crisis, a climate crisis and a crisis of loneliness.

These challenges are, of course, interlinked and can’t be successfully addressed in isolation. Reflecting this, we can look to co-creative and cross-sector strategies for paths to progress. The Phoenix Project in Inverkeithing illustrates some of the opportunities that exist for delivering progressive change through the built environment, but also highlights some outdated practices that impede innovation.

Inverkeithing (population 5,280) is in many ways a typical Scottish town – a medieval core surrounded by 20th-century housing, and pock-marked with vacant and derelict sites, the legacy of 19th-century industries. The town has the highest percentage of vacant and derelict sites in Fife, and its historic core has just begun a Conservation Area Regeneration Scheme.

A Charrette last year spurred the formation of The Inverkeithing Trust as a vehicle to take forward the community’s priorities, while the local authority reviews the future of its community facilities in the context of austerity, recently announcing the closure of the town’s cheerily modernist high school.

One of the reasons towns have such a great future is that they operate at a wonderfully human scale, and this fosters connected communities that are passionate about their place. When this combines with derelict sites, it creates opportunities for transformative change.

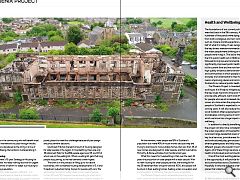

Such an opportunity is the 1-hectare site of a big Edwardian primary school lying just off the High Street, which was sold by the local authority in 2009. The site has since lain neglected, with a series of failed attempts at commercial housing, whose design approaches proved unpopular with the community and stakeholders. Just before Christmas 2018, the main building was substantially damaged in a spectacular arson attack.

This provoked a strong reaction amongst the community. The fire undoubtedly reduced the site’s townscape and architectural heritage value, but it also revealed a strong intangible social heritage in the emotional connection local people had with the site, where many had spent their formative years, building friendships and learning about life. To some degree, the site has an iconic status among the community, representing the decay of a traditional past and its potential for a better future.

After 88% voted for a community-led future for the site, the Architectural Heritage Fund, Fife Council and the Scottish Land Fund financed a feasibility study, led by a partnership of the Inverkeithing Trust and the Vivarium Trust, a housing charity. That financial support reflected the breadth of potential public benefit, while the primacy of local community control ensured its core values. The study, just completed, sets out a vison for the site that is radically different from the one offered by commercial redevelopment.

That difference founded in two things – public benefit values and a long timescale. These undoubtedly made a project slower and more complex than a commercial approach, where priorities are private profit in short timescales, but the outcomes are so much better they are worth waiting and working for.

A new kind of process

The project focuses on the key areas where it could make a difference, measured against the metric of improving the wellbeing of the people of Inverkeithing.

To develop a shared understanding of what wellbeing is, the project brought together local people with Fife Council officers, the design consultants, experts from the NHS, A+DS, academics and other organisations, using non-hierarchical processes that were developing out of the European JUMP project on innovative training for change. These processes aimed to avoid the normal barriers of power dynamics within projects that impede effective sharing of expertise and experience between communities, experts and stakeholders, to achieve a co-creative dynamic. When nobody has authority, everyone has influence.

That process demonstrated that mental health and community were seen as much more important to local wellbeing than physical health or wealth. When these characteristics were mapped against the potential initiatives that local people said they wanted, it demonstrated a strong and diverse inter-connection between place and wellbeing.

Those results formed the basis of an approach to the project as a public preventative health intervention, aiming to enhance the wellbeing of the people of Inverkeithing though place regeneration, with a focus on mental health and community resilience. Further research identified 3 key areas that the project could make a significant difference, not addressed by the public or private sectors, and these formed the core of an integrated design and business plan.

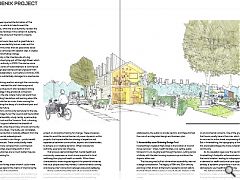

1. Accessibility as an Ordering Design Tool

Inverkeithing’s medieval High Street is the location of most of its key services – shops, health facilities, civic centre, public transport. It runs roughly level through the town, cutting across a hillside, with the later housing expansion up and down the slope to either side.

That housing was built at a time when accessibility was not a design consideration. The legacy of 19th and 20th-century planning is that almost all the town’s residents cannot walk to the High Street without going up one of 24 sets of steps or 40 pavements steeper than permitted by Building Standards for access.

Inverkeithing’s public realm thus discriminates against people with disabilities, older people, pre-school children and people who do not drive cars because of health, age, poverty or environmental concerns. One of the great advantages that towns usually have is their size, which brings proximity to services for active travel, empowering life without cars. But in Inverkeithing, the topography of the town negates this and disadvantages the more vulnerable members of its community.

As its population ages over the next 40 years, Inverkeithing’s footpaths will exacerbate inequality and fuel social isolation, leading to a disproportionate increase in demand for health and social care support. Loneliness is already at epidemic proportions in our country and more damaging to your health than smoking.

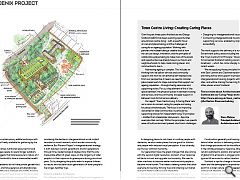

The defining primal move in the project design was therefore to create an all abilities public pedestrian route through the site, providing the only accessible way to the High Street from the west half of town. Who but a community would begin development with this?

The interesting consequence of this decision is that it then attracts all the people in the community who will benefit most from other wellbeing interventions to pass through the site. The route was therefore developed as the string in a line of pearls, with other wellbeing interventions clustered along it.

2. A New Kind of Housing

The Scottish Government’s 10-year Strategy on Housing for Older People states that ‘we need nothing less than an urgent and sustained programme of reform’ to adapt our housing to the needs of an ageing population.

Housing designed for older people is different – it is accessible, comfortable and easy to heat and maintain, within walking distance of services, and crucially it is socially clustered to avoid isolation – but we are just not building it. This a looming crisis facing all communities, and Inverkeithing is again poorly placed to meet this challenge because of past design and procurement decisions.

Southwest Fife has the least amount of housing designed for older people in the region. In Inverkeithing, there are only 39 retirement flats for the 898 people aged over 65, and 311 of whom are on the waiting list. When a waiting list gets that long people stop joining, so the real demand is even higher.

The town is in the process of filling up to its natural boundaries, with consented housing developments of 3, 4 and 5-bedroom suburban family homes for people with cars. We are building houses for today’s baby boom peak of people in their 40’s and 50’s because we are building for short-term profit and poorly targeted state incentives, creating a legacy of people under-occupying inappropriate and isolated homes as they get older, with nowhere else to go.

At the moment, older people are 18% of Scotland’s population but make 40% of house moves because they are trying to downsize to more suitable homes. But, less than 3% of new homes are designed for older people, and that was before McCarthy & Stone withdrew from Scotland last year.

What this means for Inverkeithing is that over the next 40 years the proportion of older people will at least double. With no new housing for older people planned, the waiting list for the 39 retirement flats will grow towards 1000, and people will be stuck in their existing homes, fuelling under-occupation and social isolation, amplified by the town’s poor accessibility.

The Phoenix Project uses its accessible proximity to the town centre to host an innovative housing development for older people. The fire-damaged building will be re-purposed with a block of 24-32 flats inserted inside its historic shell. The 1 and 2-bed flats are clustered in groups of 4 either side of shared spaces, in a development designed and managed by the residents themselves.

This is cohousing, where people live independent lives as part of an organised community of neighbours who share some facilities. Cohousing began in Denmark, where it was supported by the government specifically to address loneliness and it now forms the majority of new housing for older people. Other European countries with more participatory planning processes and more pluralist and localised housing delivery have followed suit, but the UK housing sector has been slow to adapt.

Scotland has policy and frustrated communities, England has a £163m budget, support centres, targeted financial schemes and a landmark exemplar, the OWCH project in London.

It is important to recognise how unusual the UK is in how it does housing, and that this is the root of the problem with poor housing supply for communities. No other comparable country provides most of its homes through 6 dominant commercial companies, not has structured its market to be so polarised between the two extremes of commercial developers and state-funded ‘affordable’ housing.

Commercial developers control land supply for housing and very efficiently provide repetitive small houses for maximum short-term profit. Homes for Scotland (representing 95% of new homes) recently gave evidence to the Scottish Government that their members had no interest in developing housing for older people.

The same working group heard evidence that government grants to support affordable housing suppress innovation and actively discriminate against older people. Social Housing grants can only be designated based on need, so cannot be used by people who want to cluster by age for mutual support. Mid-Market Rent is specifically designed for people in employment with rising income well above the state pension. Both need to be owned by an RSL (except in rural areas), which in practice prevents communities from creating housing in response to local needs.

While communities have created arts centres, sports facilities and even schools, the Scottish Land Fund, operating under Scottish Government guidance, will effectively not support community housing projects. This reflects a prevailing attitude that housing is something separate from the rest of life that is long past it’s sell-by date

There is now a widespread appreciation that the system of providing housing in Scotland is archaic, failing to meet the country’s needs, and incompatible with the Community Empowerment Act, and the Fairer Scotland Duty of the Equality Act 2010, which came into force in Scotland in April 2018, requiring public authorities to reduce inequalities of outcome when making strategic decisions.

The 2019 Planning Bill places a new duty on local authorities to specifically measure the local housing needs of older people and develop appropriate plans. When this happens, it will reveal how typical Inverkeithing’s dire situation is and the scale of change that is required in Scotland’s housing sector. We will then be desperately looking for models of how to deliver new kinds of housing to reduce the emerging crisis in health and social care.

The current Programme for Government recognises this and promised to deliver pilot projects for cohousing. The Phoenix Cohousing is designed to be one of these pilots, developing a template design, organisational structure, financial plan and grant funding model, which could be replicated by other communities.

In constructing the social architecture of an intentional community of older people, the financial plan needs to be simple and resilient. A not-for-profit community benefit company structure will enable people to join irrespective of their financial means and facilitate a smooth turnover of residents while safeguarding the public interest. This reflects the harmony between the project priorities of wellbeing and community, and personal drivers of residents, who seek company in a thriving and secure later life.

This is in stark contrast to the dominant consumer housing model which focuses on personal and corporate financial profit through individualised delivery and ownership, with very little choice. That model fails to reflect the diversity of modern Scotland and the shared stake we all have in a collaborative future.

While the Phoenix Project focuses on housing for older people because of the current demographic imperative, creating a more participatory and pluralistic housing sector will also meet the needs of other citizens of today’s diverse Scotland who are failed by the current system. The recent project in Dumfries for LGBT-friendly housing is a good example.

Another is the group of parents in Aberfeldy who have children with special needs. As the children become adults and the parents become older, they were told they would have to move to Perth of Dundee to be supported, but want instead to build their own housing where both groups can provide mutual support in the physical and social environment they feel part of.

3. Redefining what we mean by Playground

The creativity of inclusion as a design agenda also informed the Phoenix Project’s landscape design. If some cohousing residents will return to find their former school transformed into their future homes, so the tarmac where they played as children will be redefined as a recreational landscape for their 21st-century community.

Fife Council’s Greenspace Audit records that Inverkeithing has a poor provision of green space, with low quality and accessibility but lots of close mown, sloping ‘amenity grassland’.

With physical inactivity now the second biggest cause of mortality in Scotland, the Phoenix Project will create a space for unstructured play, the only playspace in the north half of the town. Rather than a fenced area for specific activities by certain ages, this will be an unenclosed area designed to encourage creative physical activity among all ages, and specifically to encourage inter-generational activity.

There will be an open amphitheatre to promote performance and collaborative events, part of a wider strategy to promote creativity that includes artists’ studios and a community workshop.

A community growing area runs between the public route and the cohousing, fostering skills sharing and providing local food. This is part of a strategy of defining the public route as a contemporary edible landscape with nuts, berries and fruit freely available for gathering by the community.

This not only enhances nutritional resources for local people but encourages people to spend longer outdoors. Current research suggests that total exposure to nature of 2 hours a week is the threshold to have a measurable benefit for mental health.

The cohousing residents do not have private gardens but share external decks and have generous private balconies projecting into a wildlife zone wrapped around the housing block. Peripheral parking and level access at first floor allow the creation of a woodland habitat, working with a shallow green roof to promote biodiversity as an example of urban re-wilding.

Our public spaces have an important role to play in countering the decline in intergenerational social contact recorded in recent research, which erodes community resilience. But Phoenix Project’s intergenerational strategy is both between current generations and for generations through time. Epidemiological studies show that the only measurable effect of green space on the longevity of older people is in their exposure to greenspace during pre-school years. So by designing the public realm to expose children to nature, we inoculate future generations of older people to live longer, healthier lives.

Towards a Habitat for Humans

The different strands of the Phoenix Project work together to define a new approach to the design and management of the public realm as a habitat for humans, reflecting the diverse physical and cognitive circumstances of our population.

In designing places to not stress or confuse people with dementia, we also create places that are good for children and people with reduced visual perception. In our diversity, we find our common humanity.

Our generation faces the great changes that are coming with the second digital revolution, and part of our response will be to re-boot and upgrade our humanity. We need to allow machines to become better machines and people to become more human. That means creating homes that allow everyone to live long, thriving lives and ordering our shared spaces to foster positive social interaction.

Community-led processes are the key to moving priorities away from vehicles and private profit and towards the long-term benefit of the people who use our public spaces, and from seeing housing not as a commodity, but as a human right fundamental to public health.

Construction generally and housing in particular lag well behind other sectors in delivering innovation, which means that change processes will be less efficient. We can see this in the climate emergency response, where construction remains addicted to plastics and cement, which alone at 8% of global CO2 emissions is a bigger problem than aviation, ignored till we move to carbon taxation.

Scotland is ripe for change in housing and the public realm and the demographic imperative may be the trigger point for a wider culture change needed to overcome commercial interests, inertia and risk aversion. Maybe we can learn a lesson by seeing design through the prism of health, where there is an expectation of progress founded in our personal human life experiences. And perhaps we will emerge from the Coronavirus with a greater appreciation of our collective endeavour.

|

|