Celtic Connection: Troubled Waters

15 Apr 2020

Amid unprecedented global tumult the temptation to build big is one constant. As uncertainty laps our own shores the talk is not of splendid isolation but enhanced connectivity. Can the dream of a British-Irish crossing survive these tempestuous times?

It has been two years since the latest audacious proposal to build a leviathan crossing between Northern Ireland and Britain but in those two years the gap between the vision and the reality seems only to have widened as political divisions have grown. Is the idea now dead in the water?

Ostensibly the concept received a major vote of confidence when Prime Minister Boris Johnson giving green lighting a scoping report to investigate the viability of a link between Portpatrick near Stranraer to Larne, north of Belfast. If its proponents are to have any success they must first bridge a chasm that runs far deeper than 300m drop of Beaufort’s Dyke – the animosity between the SNP and the Conservatives.

Scotland’s Transport Secretary Michael Matheson writing to his UK opposite number Grant Shapps called for the reputed £20bn build cost to be made available for alternative infrastructure projects but the UK government is persevering with its vision, promoting the concept of a tunnel as part of a hybrid bridge-tunnel solution to answer critics concerns around the cost and practicality of a physical connection.

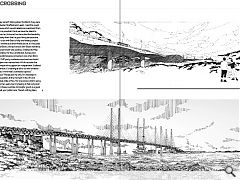

The sub-sea solution would see the crossing dip below the surface of the Irish Sea to enter a 22-mile long tunnel to escape the vagaries of wind and wave action while also reducing costs, amid concern that a single bridge solution would be too exposed to the elements. It is thought that such a tunnel could be modelled on the famous Oresund Bridge which utilises a combination of terrain dependent bridges and floating tunnels to span 12km of water between Denmark and Sweden, mediating between the two via an artificial island positioned mid-way along the route.

Identifying the potential to dig Scottish secretary Alister Jack made the suggestion during a gathering of the Scottish Parliament’s Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee when he said: “The bridge for me is a euphemism for a link … which is a tunnel. Just to be clear about that. Tunnelling techniques now are quite advanced. And certainly, to go from south-west Scotland to Northern Ireland, it would be less expensive, knowing what we know of the geography of the north channel, to tunnel it.

It’s no different to the tunnels connecting the Faroe Islands, it’s no different to the tunnels going under the fjords. Once we get a better sight of the costs involved, should the Prime Minister decide to press the button, we would then want to engage with both [the Northern Ireland assembly and the Scottish Parliament] to get a better understanding of the benefits and the challenges.”

The concept of building a physical link across the Irish Sea was revived by professor Alan Dunlop who extrapolated public costings for similar infrastructure projects such as Arup’s Queensferry Crossing, the Confederation Bridge linking Prince Edward Island to Canada and Norman Foster’s Millau Viaduct to arrive at a cost of around £20bn for the Larne route but with more recent big infrastructure projects such as Crossrail and HS2 coming off the rails any figure at this stage is open to question.

In stark contrast with America where all the talk is of building walls Britain has been busy attempting to build bridges as a means of uniting a divided populace but as the government seeks to ‘level-up’ the economy outside London is a grandiose crossing the best allocation of resources?

Appraising Urban Realm on the present state of play Dunlop said: “The Westminster idea at the time was for a Northern Powerhouse but they weren’t talking about Scotland, they were talking about Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds. I said this could be a Celtic Powerhouse which would rebalance investment from London. I believe this is possible I think we have the talent to complete this but now he (Johnson) has launched the feasibility study I don’t necessarily think that’s a good thing because the comments now are to do with Boris’s folly and fantasy project. It’s not about ideas, architecture and infrastructure, it’s focussed on people ‘s dislike of Boris Johnson and an anti-Brexit narrative.

“The Scottish Government was positive, I’d talked to Mike Russell (Cabinet Secretary for the Constitution, Europe and External Affairs). The Damascene conversion was when Boris Johnson was at the DUP party conference and said we should do the bridge and gave me a namecheck. All of a sudden the attitude changed. People who support an independent Scotland are so anti-Boris Johnson, it’s nothing at all to do with whether the bridge is possible. I think that’s a blinkered opinion.”

Dunlop continued: “People ask me why I’m interested in building bridges. The politics at the moment in the UK and Ireland is in an absolute state of flux. No-one knows what’s going to happen in the next ten years, but my feeling is that a physical connection between these countries to transfer goods is a good thing, no matter what your politics are. There’s nothing like a piece of infrastructure to say these countries are looking forward. People say never mind the bridge we should fix the potholes, the rail link to the airport is also a good idea - but it doesn’t negate the need to look at this to see if it works. I don’t see it as one or the other it’s a national debate about what we think is important.”

The rise of China is increasingly impacting upon Britain with the country ready to embrace Huawei in the teeth of vociferous opposition from the US and with reports emerging that China is angling to win a lucrative construction contract to build HS2. Might this be a readymade opportunity to fast track a link? “I don’t think it would be politically possible”, states Dunlop. I was in Wuhan in October and the infrastructure there is phenomenal. I know it’s a dictatorship, authoritarian and not a democracy but they have a much more ambitious attitude. One of the exemplar projects I looked at was the world’s longest sea bridge between Hong Kong and Macau, it’s 34 miles long and built to withstand typhoons.”

Is there a risk that if the project did get the go-ahead a run of bad news stories and mounting acrimony would end up driving a further wedge between nations? “We’re a democracy and it’s right these issues should be debated and talked about,” says Dunlop. “We need a pro-risk attitude. Look at the Forth Rail Bridge, can you imagine the balls you had to have to do that cantilevered structure? I’d like to have been around to read the criticism of that. It’s now an icon for Scotland. Very often as a country we’re more likely to be critical and look for things that go wrong.”

Bruising battles have persuaded Dunlop to adopt a (comparatively) low profile, shying away from Urban Realm website and social media after becoming a focal point for critics but he remains unbowed: “I’m not on Twitter, or Facebook because I read enough comments about myself on news articles. I’d hate to think what it’d be like if the discussion about the bridge goes on Twitter!”

Despite the odds being stacked against it, Dunlop remains bullish about his pet project, with interest at the highest levels of government proving that it’s no mere pipe dream. He said: “I’ve had a good number of engineers and contractors wanting to form design teams. The interest ebbs and flows. I’d like to think in 20-30 years there will be a bridge connection. It’s going to happen it’s part of Celtic folklore about the giant stepping from Scotland to Ireland. It’s part of who we are as Celts.”

With the COP26 climate conference coming into focus this November in Glasgow, sustainable travel is set to become a key battleground in the drive to reduce carbon emissions. With the Scottish Government committed to making every car electric by 2035 the notion of travelling between Scotland and Ireland by rail rather than air may be an idea whose time has come.

|

|