Motorsport Museum: Chequered History

14 Jan 2020

Deep in the Scottish Borders the reimagined Jim Clark Motorsport Museum has shifted up a gear, drawing petrol heads and history buffs alike to relive a unique period in sporting history but is its broader contribution to the future of Duns a racing certainty?

Scottish Borders Council has crossed the finishing line with a newly refurbished £1.6m museum in Duns dedicated to the achievements of British Formula 1 champion Jim Clark. Opened this summer the Jim Clark Motorsport Museum has been designed in-house by the council’s own architects’ to memorialise a sportsman whose career was tragically cut short at the age of just 32 after a fatal racing accident at Hockenheim, Germany, but who remains loved to this day.

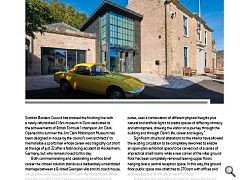

Both commemorating and celebrating an all too brief career the chosen solution stands as a deliberately understated marriage between a B-listed Georgian villa and its coach house, which previously housed the Jim Clark Memorial Room. More than the sum of its parts the new museum provides much needed additional display space by way of a black zinc linking structure which connects both buildings and doubles as a public entrance.

The central concept focusses on a visitor journey navigating the life and career of Jim Clark, arranged in the manner of a racetrack and resembles the initial sketches remarkably closely, save for the rationalisation of vertical circulation and removal of a viewing gantry above the vehicle display pen on value engineering grounds. Bringing Urban Realm up to speed on what has proven to be a marathon rather than a sprint for Ray Cherry, architectural manager at Scottish Borders Council. He said: “The creation of a single space, subdivided into different zones, uses a combination of different physical heights plus natural and artificial lights to create spaces of differing intimacy and atmosphere, drawing the visitor on a journey through the building and through Clark’s life, career and legacy.”

Significant structural alterations to the interior have allowed the existing circulation to be completely reworked to enable an open-plan exhibition space to be carved out of a series of impractical small rooms while a rear corner of the villas ground floor has been completely removed leaving upper floors hanging over a central reception space. In this way, the ground floor public space now stretches to 270sqm with offices and archives located on a more private first floor.

Asked why the decision was taken to deliver the design in-house instead of opening up the process Cherry said: “Why wouldn’t we is the simple answer. The team is connected with the local area and understands the value of a building of this nature to the community and the built environment. It also has the advantage that the ‘after care’ of the building is available ‘on tap’. When the building is completed, we don’t hand over the keys and walk away, but remain available to respond to clients’ requests for information. I still receive calls from occupants of buildings that I designed and built twenty years ago asking for information about the original design or the materials and components used.”

Complicating matters somewhat was the aforementioned requirement to work within the confines of the existing B-listed villa and coach house. Did this limit the freedom of expression which a blank canvas could have provided? “There is the obvious legislative issue of the Listed Building Framework but my experience with Historic Environment Scotland (HES) has been an incredibly positive one”, claims Cherry. “Some of the proposals were radical, especially in conservation terms, such as the removal of the central staircase and effectively, the removal of all of the existing rooms on the ground floor, but HES listened to the design rationale and were supportive of my proposals to adapt an existing building in a manner that would extend its life span into the future. Part of the challenge was developing a design that could allow the character of the existing buildings to be retained and integrated with the new museum.”

The challenge was compounded by the fact that parts of the old coach house were so unsafe that they could not be properly surveyed. When the team finally moved on-site they were greeted by a situation which was even worse than expected, forcing the construction solution to be changed at short notice though these problems were allayed by a collaborative approach with the council’s own conservation officer. Moreover, the existence of two disparate elements presented the need for some form of unification, ultimately resulting in the creation of an atrium link which doubles as a front door. “This was a particular challenge that works on different planes and required the use of specific materials.” observed Cherry. “On plan, the coach house is set back from the villa so I opted for the link building, which forms the new level access entrance, to sit back from the villa, but forward of the coach house to maintain the superiority of the villa to the street front. This was repeated with the front elevation heights by keeping the link lower than the villa parapet. The roof form is also purposely different from the existing slated, pitched roofs to reflect the intervention.

“I spent a lot of time considering the most appropriate materials for the new-build section and the original sketch has this as a glass box – essentially to create a transparent link, but the reality was that this would have been wholly impractical from a curator’s perspective. The impact of UV radiation on exhibits and the overheating implications would have required additional servicing costs to mitigate and would only add to the revenue burden of the client. Museums, especially provincial ones, have to operate on incredibly tight margins, therefore it is incumbent on designers to respond to this. The design developed to the use of a traditional, rural (agricultural) material – zinc – in a contemporary fashion as a means of addressing operational demands while reflecting the quality of the original listed building and promoting the forward looking aspirations of the new museum. The pre-patinated anthracite colour of the zinc, combined with the white glass were chosen to make the link recede while remaining purposefully contemporary. The passer-by simultaneously sees an original villa of architectural merit and a quality modern museum that invites their further attention.”

Quizzed by Urban Realm on the apparent dichotomy between an architecturally modest but structurally flamboyant solution Cherry responded: “I think it is to misunderstand or misinterpret to suggest that the design vs structure relationship is like this. Yes, the overall museum design is purposefully, apparently modest, but it is deceptively complex. Its modesty was a deliberate response to the context of the existing building and also, fundamentally, in tribute to Jim Clark himself who has been described by many people as a modest man, despite his enormous success. The structural intervention is a direct result of function and the design intent of a museum that flows, allowing the visitor to enjoy the experience and the exhibits without being distracted unnecessarily by the building.

“Most visitors comment on the ‘Tardis-like’ nature of the space and are taken aback when they enter by just how large and open the space is; a direct counterpoint to the “modest” frontage. The interplay of natural and artificial light with shifts in volume height add to this dynamic in a way that guides the visitor naturally through the spaces. Intimacy is created in the most sensitive areas by using the original, restricted ceiling height along with the removal of all natural light, black surfaces and the careful design of the exhibition display fitments.”

Asked what Jim Clark himself would make of all the fuss and attention fifty years on Cherry said: “I am too young to remember Jim Clark when he was racing, but I do know members of his family and they have all said that this very modest champion would have been humbled and delighted by this building. This was echoed by his great friend, Sir Jackie Stewart, at the official opening of the building in August. From the stories I have been told about Jim Clark, I suspect that he would be slightly embarrassed by the attention, but also immensely proud to have this museum in his name. “

More than just a museum the attraction forms a key plank of efforts to regenerate Duns, attested to by the fact that 12,000 visitors have already passed through its doors, with just 18% of these visits originating from within the Scottish Borders. This impact is augmented by the deliberate omission of a café or on-site parking, to ensure that any spillover benefits to the local economy are maximised.

The public are already lapping up the museum according to preliminary numbers but its true impact will be measured on the wider town which looks set to capitalise by earning a ranking on the tourism circuit. Fifty years on from Jim Clark’s untimely death the racing legend has taken pole position once again.

|

|