Classical Edinburgh: Character Witness

13 Jan 2020

Leslie Howson presents the case for an urgent new protection plan to be put in place for Edinburgh’s rich neo-classical heritage. Here Howson considers a rich architectural legacy and its significance as a springboard for the city’s future development.

Classical Edinburgh with its iconic seven new towns was the result of a clear vision which followed the period of the Enlightenment and from a determination to make Edinburgh one of the foremost capital cities of 18th century Europe. James Craig`s masterly first New Town plan of 1767 created a neo-classical extension for Edinburgh, planned and largely built within 30 years and which soon became the envy of 18th century Europe. Over the next, circa 100 years Edinburgh became a city which the world now comes to see as much for this unique classical heritage as for its equally iconic medieval Old Town, the Castle and the Royal Palace.

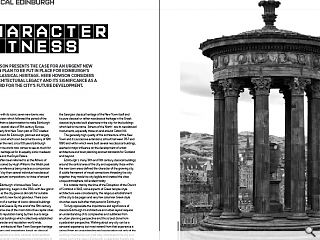

Edinburgh has often been referred to as the Athens of the North, a phrase coined by Hugh Williams the Welsh poet and artist in 1820, the reference being made as a comparison between Edinburgh’s by then several individual neoclassical buildings and architectural compositions, to those of ancient Greece.

The building of Edinburgh`s famous New Town, a masterpiece of city planning, began in the 1760s with few grand public buildings but as the city grew so did calls for suitable monuments to cement its new found grandeur. There soon followed the erection of a number of iconic classical buildings reminiscent of classical Greece. By the end of the 19th century, Edinburgh had become one of the most distinctive capital cities in Europe, much of its reputation being by then due to large number of neoclassical buildings which collectively established the cities unique character and reputation world wide.

Whilst the cities architectural New Town Georgian heritage is marked by symmetry and proportions based on classical features; columns, capitals and other classical ornamentation are restrained and secondary to the essential characteristics of the Georgian style. Thus a distinction has to be made between the Georgian classical heritage of the New Town itself and its pure classical or rather neoclassical heritage in the Greek classical style also built elsewhere in the city; for the buildings which led to the name `Athens of the North` are its neoclassical monuments, especially those on and around Calton Hill.

The generally high quality of the architecture of the New Town and its successive extensions, all built between 1767 and 1890 and within which were built several neoclassical buildings, exerted a major influence on the development of urban architecture and town planning and set standards for Scotland and beyond.

Edinburgh`s many 18th and 19th century classical buildings around the central area of the city and especially those within the new town areas defined the character of the growing city. A subtle framework of visual connections threading the city together, they made the city legible and created the cities unique atmosphere, still evident today.

It is notable that by the time of the Disruption of the Church of Scotland in 1843, some aspects of Greek temple-style architecture were considered by the religious establishment of the city to be pagan and very few columnar Greek-style churches were built after that period in Edinburgh.

To fully appreciate the importance and significance of classical Edinburgh its architecture and urban layout requires an understanding of its complexities and subtleties from an urban planning perspective and this is best done from a pedestrian perspective. Walking about any city can be a sensorial experience but most reward from that experience is gained from an understanding and appreciation not only of the buildings themselves but what they contribute to the city as a whole; such is the case in Edinburgh, a pedestrian friendly city.

It is not only a matter of the perception of the buildings themselves but also recognizing building compositions, the interplay of the buildings and their spatial context, buildings in the wider urban and landscape setting and about the role they play in making for visual connections an aspect which makes the city more legible.

Historically, the urban expansion of Edinburgh has been a series of paradigms reflective of the major periods of its development with each imposing variations to the urban grain of the city. Within each period many major landmark buildings were built which help define the cities character. Visitors today experience a series neoclassical architectural masterpieces, each punctuating the urban plan, framed vistas, set pieces and compositions which all combine to create the particular music of the city. This is the delight of Edinburgh and which must be understood by city planners, architects and developers alike.

Whether such architectural monuments appear within the New Town and its subsequent extensions or elsewhere in the city, these familiar buildings are important enhancing landmarks, which along with the castle rock and the Old Town give the city its special character.

Located in a unique landscape setting and juxtaposed to its castle on a rock and with its medieval old town, Edinburgh has a great legacy of classical architecture to rival any city in the world.

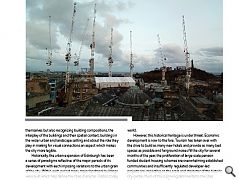

However, this historical heritage is under threat. Economic development is now to the fore. Tourism has taken over with the drive to build as many new hotels and provide as many bed spaces as possible and fairground noises fill the city for several months of the year, the proliferation of large scale pension funded student housing schemes are overwhelming established communities and insufficiently regulated developer-led projects are impacting on the scale and character of the historic city centre. Much of this is proving detrimental to the cities World Heritage legitimacy. The economic returns to the city from tourism are set to destroy the very aspects which most tourists (and scholars) come to see, perhaps its greatest asset, its historic built environment. Whilst every city needs inward investment in the form of new development, there has to be a balance between what is appropriate development and erosion of the city’s historic heritage.

The classical city is constantly under threat and many would say is today being ruined from inappropriate and insensitive development mostly driven by economics. This has resulted in a gradual erosion of the cities important historic legacy and character as new badly designed buildings are juxtaposed to old and supposedly protected cross-city vistas are being interrupted by over-scaled developments imposing themselves on the city skyline.

The potential for a negative impact from inappropriately designed development in Edinburgh is evident, despite presumed protection of key vistas and supposed restrictions on building heights in the central area of the city.

Whilst Edinburgh has seen the building of many well designed individual buildings they have not necessarily positively contributed to the whole. That all new buildings should be representative of their period is an accepted tenet but equally is the principle that building should contribute and enhance their context. This is especially so in a city centre like Edinburgh where a single inappropriately designed or over-scaled development can have a huge detrimental and character changing impact on the cities urban landscape. It is the collective responsibility of architects, planners, developers, conservationist and the city authorities, as joint guardians of Edinburgh’s unique environment to see that this does not happen.

It should be remembered that in 1967 Edinburgh’s architects gathered to survey and protect the cities then crumbling classical buildings, many under threat of demolition; thus an example of collective concern and collective action to safeguard the cities heritage. Some would say Edinburgh is under threat again but this time not from crumbling buildings, albeit preservation of the cities’ historic built fabric must continue and extra vigilance to offset the detrimental effects of climate change.

Classical Edinburgh started with a clear vision which came out of a period of enlightenment, political circumstance, social change and the need to establish a new Scottish identity. Within approximately 100 years the vision and desire for a new beginning spawned the historic city of today a great legacy which the city has prospered from. The question which historians, conservationists, urban planner and architects should be asking now is what legacy are we creating for the next 100 years. Everything we plan today and build today will leave a legacy and as cities grow and become more dense, getting that legacy right becomes ever more important. Therefore we have to consider whether what we are building today is anywhere near as good as classical Edinburgh which was master-planned and then grew incrementally and purposefully to create this iconic city.

At a time when the city is devising its Vision for 2050, there is arguably a need to take stock and consider how the city should be shaped in the future and conserving and safeguarding its architecture and urban planning heritages is central to that process.

A more holistic and urban design approach to the future shaping of the city is arguably required and with this a more considered approach to how new large scale developments building should fit into the city-wide context and their contribution to the overall character of the growing city. Perhaps changes should be made to the current planning process, moving away from a predominantly developer-led system to one which considers the wider impact of such developments on the overall character of the city and its communities.

It is the case that throughout Edinburgh`s history, boldness and civic vision has been to the fore. Creation of the New Town, the building of the North Bridge, extending the railway network through the city and the building of Waverley Station (soon to be revamped) were bold initiatives but respectful to heritage.

Radical changes are being made again as the city grows, however, unlike the classical period of the 18th and 19th century, there is currently no overall vision for the planning of the city. Current master planning is for private landowners, site limited and commercially driven with no consideration about how such development will impact on wider context resulting in a gradual erosion of the character of the city.

There is perhaps more public criticism now about insensitive and inappropriate large scale developments than in the recent past, when such as the Castle Terrace / Traverse Theatre complex appeared to come under greater scrutiny by Planning than now. This was then not just about architectural design quality but also about urban design, with considerations such as the impact such large scale developments would have on the city skyline, an aspect which Planning appears to be more relaxed about now, unfortunately. The lack of in house urban designers due to cuts in human resources within the Council, may excuse this apparent ‘weakness’; in the planning process but if City Planning cannot be allowed to ensure a high standard of urban planning is maintained within the city, then who can?

The building of Edinburgh`s classical architecture grew out of a desire to enhance the cities profile and the reputation of Scotland but at the same time central to this aim was the conscious level of control exerted by the city authorities to ensure that the new buildings on a scale never previously conceived or built so quickly were of the highest quality design by the best intellectually minded architects and all within a highly controlled urban planning process; the first New Town and its subsequent phases are clear evidence of that. The city grew and thrived and with a need to draw investment as now, but it that growth was balanced against a desire to safeguard and to respect the cities great historical heritage. This same conscious and conscientious approach is required now, otherwise, its unique heritage will be lost for good.

|

|