Georgian Edinburgh: Classical Views

13 Jan 2020

An eye opening photography exhibition puts Edinburgh’s New Town in the frame with a series of views charting the evolution of its neo-classical architecture over the past half century. Photographer Colin Mclean steps out from behind the lens to tell us more.

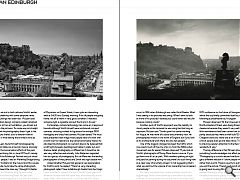

Fresh from pounding the streets of Edinburgh in pursuit of evocative snapshots of the timeless New Town, photographer Colin McLean has created a link to the past by pairing the seminal work of photographer Edwin Smith with his own work at Classical Edinburgh, an exhibition charting the changes, overt and subtle, which have altered the New Town for good and ill over the past 50 years.

By mixing archive images reproduced in A.J. Youngson’s seminal 1966 book ‘The Making of Classical Edinburgh’ with new and updated perspectives of the city as it appears today the exhibition serves as a time machine taking us back to an era which is gradually fading from our collective memory. Thrust back into the spotlight with high-resolution you can almost step into the smog-bound Georgian streets the exhibition serves as a celebration of the courageous conservation efforts of the day which bequeathed the New Town as we now know it but which also serves as a reminder of its ongoing fragility.

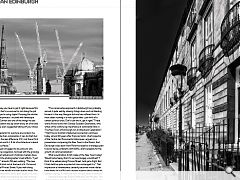

Digging deeper than the surface Craigleith stone, slate and cast iron that draws tourists from the world over McLean is keen to imbue his images with the storied history of an area which has not only been a seat of philosophy, economics and science but also a home to the world’s oldest profession. McLean said: “Someone once asked me what my favourite street was, and I said Danube Street. Number 17 was a very famous brothel for about 40 years! There are all sorts of these streets tucked away which many of us don’t see.”

McLean’s risqué tale is a reminder that behind the po-faced Georgian facades the lives of the people who lived and worked here could be every bit as colourful as their less well to do Old Town neighbours, despite the monochrome artistic choices of the photographer. Sadly, the exhibition never ventures behind the net curtains with McLean admitting he had wished to photograph some interiors but ran out of time.

Instead, McLean set out to both reframe Smith’s earlier work and to flex his creativity with some bespoke views where the original buildings had been lost. McLean said: “I recruited an exhibition design company called Campbell and co who said, ‘this isn’t an art exhibition, you should put more of yourself into the pictures.’ So some are not straight reshoots. I like to think the photography doesn’t get in the way of the architecture, there’s a bit of tension there in putting yourself into it while letting the architect shine as well.”

Unlike Smith McLean found himself handicapped by Edinburgh’s newfound status as a tourism mecca, ironically built in large part on the conservation efforts of the past. McLean said: “I started doing this in June 2017 and I naively went in the middle of the Edinburgh Festival and just stood in front of millions of people. I was on Waverley Bridge taking a shot of the Bank of Scotland on the mound and this couple came and stood beside me to take the same photograph. As they walked off I heard the man say ‘I thought I’d better capture it, he looked as if he knew what he was doing!’

Seeking refuge in the witching hours McLean then attempted some early morning recce’s, but soon discovered these nocturnal jaunts presented their own set of difficulties: McLean continued: “I was photographing the Royal College of Physicians on Queen Street, it was quite an interesting walk at 04:30 on a Sunday morning. A lot of people are going home, not all of them in very good condition. I watched someone light a cigarette and put the lit end in his ear.”

Fortunately, camera technology has come on in leaps and bounds although Smith himself never embraced compact cameras, choosing instead to lug around an antique 1900 mahogany and brass field camera. McLean stated: “He must have presented that image most people have of a man with a cloth over his head and a big camera and heavy tripod. He also liked to photograph on overcast days as he believed that a soft light showed a buildings best detail. I prefer sun and shadow detail, photography is different as it should be. He was very reflective and actually, John Betjeman regarded him as a genius of photography. Eric de Mare was the leading photographer of that period and Smith was right beside him.”

Asked whether McLean had gained a new appreciation for Smith’s work, he replied: “There’s a very interesting photograph called ‘View to Edinburgh Castle from the Crags’, I went one day to reshoot that and I couldn’t quite work out where his horizon over the castle was, which was only a mile away. When I took the picture, I could see the Five Sisters Bing at West Calder and the Forth Bridges. It’s not because I’ve got a better camera, it’s because it was before the clean air act in 1956 when Edinburgh was called Auld Reekie. What I was seeing in his pictures was smog. When I went to look at more of his pictures I realised you could never see very far because nobody could.”

Another quirk of Smith’s approach was the inability to shoot people as the cameras he was using had too long an exposure. McLean said: “Smith spent his career working for Vogue, he was more of a social documentary man. He photographed miners in the north of England but if you look at his architectural work there are very few people.”

One of the biggest changes has been the traffic which now snarls much of the city, a far cry from the 1960s when movement was far easier. McLean observed: “If you look at Smith’s photographs of Moray Place there is one car. If you go there now it’s a car park. With residents parking at night and paid for parking during the day there’s no such thing now as a clear view of an empty street. I’m not suggesting that’s what we want but the volume of car ownership has increased dramatically.”

Far more important than a mere nostalgic record of a bygone age Smith’s work serves as a reminder of a critical moment in history when much of the new Town might have been lost but for the timely intervention of a passionate group of architects and surveyors, culminating in a pivotal 1970 conference on the future of Georgian Edinburgh at which the city finally committed itself to preservation following a presentation by Youngson.

McLean observed: “At the time even streets like Northumberland Street were being threatened with clearance because they weren’t very well looked after. Very little maintenance had been carried out on the buildings, partly because they were so well built 150 years earlier with Craigleith stone but there was a lot of work needed. It made a lot of people look up and take notice. The book was critical to drawing people’s attention to the New Town and how wonderful it was.”

The key difference is that McLean shoots digitally, something he acknowledges can affect perceptions: “Photography is a much-abused medium and I know that I get a different reaction if I show people images on my iPad rather than a print. There’s a purity to a photograph, it’s just you and the picture. There’s a school of photography that is going back to using film again. I was in a shop watching people listening to music on a £14k turntable and realised it’s not about the sound quality. It’s that analogue experience.”

Is there an argument that digital photography is more disposable and that you can just spray and pray instead of composing shots? “I don’t subscribe to that”, says McLean. “I’ve heard people say you have to get it right because film is so expensive but that’s no excuse for not doing the job right just because you’re using digital. Pressing the shutter is the last step of the process. I studied with landscape photographer Joe Cornish and one of the things he said when he gets on location was lay down every bit of kit and just walk around. He even suggested taking off your shoes and socks.

“The three ingredients for a picture are content, the clients got to provide that, composition (I can do that) but light is what makes the real difference. If it’s not there I find myself saying it’s not worth it. A lot of architecture is about the play of light on surfaces.”

One street McLean struggled to do justice to was George Street where congestion, twinned with the growing requirements of the Festival and Christmas markets have conspired to thwart the photographer’s best efforts. “I just can’t get it to work”, laments McLean, adding: “The new St James Centre will stick out at the back of it. It’s bound to draw shops out of Princes Street. If you walk along Princes Street there are hardly any high-quality shops. For a street with unrivalled views, that’s quite bizarre. It’s a bit more pedestrian-friendly now because you can’t drive as easily with the trams. I was struck by the amount of tram infrastructure in the form of all the cables.

“The conservative approach in Edinburgh has probably served it quite well by slowing things down and not blasting forward in the way Glasgow did and has suffered from. In most cases rushing in is not a good idea - just think of a certain political crisis. Don’t rush into it, get it right!” These words find an echo with Clarisse Goddard Desmarest, who writes of the continuing importance of continental links in ‘The New Town of Edinburgh: An Architectural Celebration’: “That Franco-Scottish intellectual connection continues today, almost 50 years after Francois Sorlin, chief inspector of the Centre des Monuments Historiques, argued, in a presentation comparing the New Town to the Marais, that Edinburgh could learn from Paris the need for a strategic plan to avoid decay, problems with traffic, and to prepare for the growth of commercialisation.”

What would Edwin Smith make of the New Town today? Would he be happy that it’s survived largely unscathed? “I think if he walked along Princes Street, he’d get a fright. But I think he’d be quite surprised at how unchanged it is.” That impression of timelessness certainly becomes more vital as time wears on but McLean cautions against taking things for granted, saying: “It made me look. You just need to look too.”

Classical Edinburgh: Edwin Smith and Colin McLean, Two photographers, Fifty Years Apart, runs at the City Art Centre to 8 March.

|

|