Tourism: Last Resort

21 Oct 2019

Tourism is a key component of our economy. It employs over 200,000 people and is one of the major drivers in shaping Scotland’s urban and rural environment. Alistair Scott of architects Smith Scott Mullan Associates considers the issues and calls for a more considered response from the design community.

It’s impossible to work in Edinburgh and ignore the current debate on tourism. Local papers and twitter posts carry a new language of tourist-speak as “glampers”, “flashpackers” and “grey pioneers” invade the city and responding to “over-tourism” is a rapidly emerging policy area for our local authority.

It is a serious issue and we are certainly not alone. Venice is banning cruise ships from the Lagoon, Florence makes bus tours decant and walk and climbers even queue to stand on the summit of Everest! All this is happening now and we designers are ideally placed to help provide some solutions.

Personally I think it is great that people can visit other cities, gain inspiration and exchange ideas. I accept the paradox of enjoying being a visitor while wanting to be the only one, but am becoming more aware of the growing negative impacts and our reluctance to adequately address them.

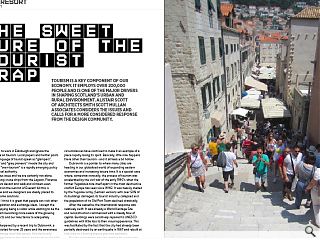

This was sharpened by a recent trip to Dubrovnik, a city I had not visited for over 25 years and the awareness of a massive change over that period. Architecturally stunning, sitting between mountains and an azure sea with ancient walls and fine buildings, there is a lot to like, but circumstances have contrived to make it an example of a place rapidly losing its spirit. Basically, little now happens there other than tourism - and it all feels a bit hollow.

Dubrovnik is a pointer to where many cities are heading in our globalised world of expanding eastern economies and increasing leisure time. It is a special case where, somewhat ironically, the process of tourism was accelerated by the civil war of the early 1990’s when the former Yugoslavia tore itself apart in the most destructive conflict Europe has seen since WW2. It was heavily shelled by the Yugoslav army (Serbian version) with over 50% of its buildings damaged, its tourist industry collapsed and the population of its Old Port Town declined drastically.

After the ceasefire, the international response was relatively swift. It was already a World Heritage Site and reconstruction commenced with a steady flow of capital. Buildings were sensitively repaired to UNESCO guidelines with little loss to their visual appearance. This was facilitated by the fact that the city had already been partially destroyed by an earthquake in 1667 and rebuilt at that time to a homogeneous plan and aesthetic.

But this programme was the catalyst for a new type of Dubrovnik. Previous residents and businesses in the old Port did not return, existing owners sold up and relocated to the outskirts and a whole new tourist economy grew with an expanding new city of marinas and hotels. These new areas are well enough planned and attractive, with effort made to integrate with the landscape, but the effect on the Old Town was significant.

The refurbished buildings became restaurants and the houses holiday apartments, but with a lack of the ordinary things that make up the daily life of a normal city, the small shops, the bakeries, the offices where people work. There is not even much sign of craft industries, the jewellers, artists, potters and even craft brewers. They appear have headed off to more affordable premises up the coast.

The municipal organisation is impressive, not a spot of litter can be seen, the streets are cleaned each morning and all these shops and restaurants are, I am told, serviced at night, which is a real undertaking as around half the city is built on a mountainside. When I last visited, these iconic stepped passages were the domain of donkeys carrying goods up and down to houses and shops, but now sadly all gone – hopefully to some comfortable sanctuary.

All this has brought a type of success, much of Game of Thrones was filmed there and vast cruise ships disgorge waves of visitors who seem delighted with what they see and if you are only there for a day then that is probably fine. It is easy to condemn tourism, but it is also worth considering what would have happened to bombed-out Dubrovnik had the tourist economy not existed!

In Scotland we need to consider the sustainability of our tourism and how our towns and cities can continue to provide visitors with inspiration and delight well into the future. For me there are two critical aspects to this, getting visitors around our country and allowing them to enjoy our Heritage without destroying it.

Sustainable tourism needs to start with transport and the environmental impact of air travel, particularly as the major expansion in tourism is from Asia. There is no easy answer to this other than restriction or a belief in technology providing carbon free air travel, but continued growth will create major problems. However we are not doing nearly enough to promote forms of land travel to encourage UK and European visitors to avoid flying.

Visitors tend to cluster and policies encouraging visitors to spread out and visit less well known places is vital (although the North Coast 500 has become almost a victim of its own success).

Getting to the edge is always attractive and our practice been involved in a series of projects to enhance small seaside towns such as Stranraer, Carradale and Applecross. These all have wonderful natural assets and often a fairly small intervention can make a substantial impact. However this process needs to me carried out comprehensively across Scotland.

Creating attractive transport links and mini-destinations can draw visitors to locations and designers need to be involved. The recent Scottish Scenic Viewpoints project was a highly successful example of how design imagination could create memorable destinations from a minimal budget. Hopefully the forthcoming 2020 Year of Coast and Water will act as a catalyst for this agenda.

We all know that one of the main reasons given for visiting Scotland is our heritage and this is inextricably linked to our historic towns and cities. It is here that the design of our environment is critical, to address over-tourism and the eventual “Dubrovnikisation” of our key historic city cores. This is not just taking care of historic structures, but enhancing the whole environment and ensuring that the activities that make a city interesting to visit are allowed to flourish.

Many organisations have Tourism Strategies, from The Scottish Government and Visit Scotland to Local Authorities, but they are usually centred on commercial agendas and plans to constantly increase numbers. In Edinburgh, our local civic society, The Cockburn Association, has been particularly vocal in promoting quality issues and we need to develop that agenda.

As I mentioned, in Dubrovnik (and many cities) there is a definite loss of the feeling of them being real and thriving place. Edinburgh World Heritage has in the last few weeks published a study looking at that difficult subject of “authenticity” and how different people perceive it and this moves the debate towards design issues and the appropriateness of strategies for individual situations.

We tend to use of descriptions like ”theme park” and “Disneyland” in a disparaging way without considering the pleasure many people obviously get from them and some (like Harry Potter Land in Universal Studios in LA) are indeed powerful “places” in their own right. However that is absolutely no reason to allow our historic cities to follow that path.

Current policy debates on the control of short-term lets such as Air BNB and introducing a Transient Visitor Supplement (Tourist Tax) shows a desire to tackle these issues. Visit Scotland calculates that tourism contributes around £11 billion to our economy and much of this based in our historic urban centres, but it seems very little of that makes its way to supporting our crumbling listed buildings, repairing pavements or providing decent refuse collection, so addressing this funding gap is vital.

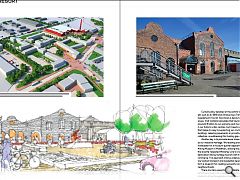

Another key is to promote lesser known aspects such as our industrial heritage. We recently produced the masterplan for a museum quarter adjacent to the Scottish Mining Museum in Midlothian, utilising the proximity of the recently reopened Waverley Line to create a new destination linking heritage tourism with housing and commerce. This approach, linking underused assets with low-carbon transport and residential developments could form a blueprint for creating successful contemporary neighbourhoods.

There are many aspects to this debate and few definitive answers. As a design community it is time we started to drive the agendas of quality and sustainability, to promote our country and protect its precious assets.

|

|