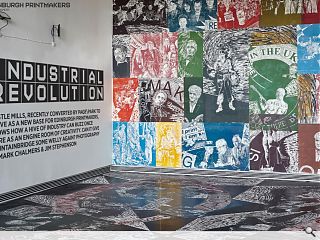

Edinburgh Printmakers: Industrial Revolution

10 Jul 2019

Castle Mills, recently converted by Page\Park to serve as a new base for Edinburgh Printmakers, shows how a hive of industry can buzz once more as an engine room of creativity. But can it give Fountainbridge some much needed welly again? Photography by Mark Ckalmers and Jim Stephenson

Generations of workers have passed through the doors of Castle Mills, a centuries-old industrial site near the Edinburgh end of the Union Canal. The building’s recent transformation, into one of the country’s biggest fine art printmaking facilities, adds another layer to its history. The Fountainbridge area industrialised rapidly following the construction of the Lochrin Canal Basin in the 1820’s.

Castle Silk Mills was built at Gilmore Park in 1836 and manufactured Kashmir shawls until a new wonder material came along – India rubber. The North British Rubber Company pioneered the use of rubber and Castle Mills is claimed to be the birthplace of the wellington boot, the motor car tyre and the traffic cone. The company’s roots go back to the dark period in our history when the use of “Scotland” as a signifier was unfashionable, a hangover from the Act of Proscription in 1746. Nearby you also had the North British Hotel, North British Distillery and North British Railway. The firm grew to employ thousands of people, and North British Rubber’s offices on Dundee Street were built around 1875, extended in the 1890’s, then embellished by the Edwardians.

As late as the 1950’s, the firm was Edinburgh’s largest industrial employer, making car, lorry and motorbike tyres as well as conveyor belts, mackintosh raincoats, hot water bottles, rubber flooring and golf balls. However, tyre production moved to a new factory at Newbridge during the 1960’s, and welly boot manufacturing went to the old Arrol-Johnston car plant in Dumfries. In 1969, a huge fire spelled the end for Castle Mills, which was sold to Scottish & Newcastle Breweries then demolished – apart from the offices at the corner of Gilmore Park – and a new McEwan’s brewery built on the site. Fountain Brewery was a complex of bottling halls and brewhouse towers with glazed lanterns, all tied together by tunnels, bridges and pipeways. On the highest tower, facing the Union Canal, was the giant head of Frans Hals’ painting The Laughing Cavalier, which is McEwans’ logo.

James Meek’s description of the brewery, in his novel “McFarlane Boils the Sea”, captured my imagination while I was still at school – “Steam boils up into the night sky from the brewery that sprawls between the railway and the canal. Lit by arc-lights, made opaque by the cold, the steam rises over thousands of metal barrels and the fleet of lorries which transport them, grumbling off on nocturnal deliveries, farting compressed air. The plant is bisected by a road; a causeway of piping joins the two halves, pumping vatfuls of foaming yellow and brown liquid to and fro.” When McEwan’s stopped brewing in 2005, the clearance process repeated itself. I photographed the empty brewery in 2008 and it felt very much on borrowed time: Bank of Scotland had offered £100m for the site, on which it intended to build a new headquarters. However, the Credit Crunch did for Fountainbridge as for the bankers’ other vanity projects, the scheme was shelved and demolition ensued. Yet the offices at the corner of Gilmore Park survived, again. If you could assign human emotions to a building, you’d say that by that point Castle Mills looked morose.

The polychromatic brickwork had been painted out dark brown: the type of urban camouflage you’d expect of a back-street establishment in a seamy part of town. Nevertheless, the building was listed Grade C and sought a new use. Edinburgh Printmakers stepped forward, with City of Edinburgh Council acting as matchmaker. Established in 1967 as the first open access studio in the UK, Edinburgh Printmakers have inhabited other industrial buildings such as the former fruitmarket beside Waverley Station and a communal washhouse near Broughton. There’s a congruence between artistic production and industrial buildings – but finding property that’s available, affordable and malleable also has a lot to do with it. I’ve set out the site’s history in detail, not only because so much has been incorporated into the renovated building, but aspects became the generative idea for the conversion scheme.

Yet history and character are one thing, but the project only became real after a Heritage Lottery Fund grant and awards from Historic Environment Scotland and Creative Scotland enabled Edinburgh Printmakers to progress the scheme. The conversion of Castle Mills began in 2012, supported by the Fountainbridge Canalside Initiative, and Page\Park Architects were appointed in 2014 to reshape the building. What remained after North British Rubber, Scottish & Newcastle and the demolition men was an L-shaped block, with a frontage to Dundee Street and return leg which curves and kinks up Gilmore Park, rising towards the canal. The renovated Castle Mills provides EP with a larger printmaking studio, more gallery and archive space, a café and shop, an artist’s flat for residencies, and scope to carry out more work with schools and community groups. “A more rounded visitor experience,” as Ursula Pretsch of Edinburgh Printmakers put it as we walked around the building.

The grandest space is the former entrance on Gilmore Park, which was remodelled in 1916 with elaborate mouldings, coloured terrazzo and decorative ironwork. Its sombre feel is down to the dark timber and cool greys, a rare surviving interior from the time of the Great War. Yet thanks to a flight of steps which defeats accessibility, it’s been reduced to a staff entrance, while a new colonnade opened up along Dundee Street forms the main public access. From there, you can interrogate how Castle Mills works. It’s evident that there were three big decisions to make: choosing to relocate the main entrance, determining where to locate the printmaking studio and deciding how to treat the historic fabric.

Arguably most important is the organising principle of the building. Should it be centred around a social space such as the café and shop – or a creative space like the printmaking studio? Printmaking lies at the heart of Western culture: we have the printing press to thank for universal literacy. Gutenberg’s printing press made books, and the knowledge they contained, available to everyone. Fine art printmakers, using everything from imagesetters and lithography to etching and woodcut, have extended that to our visual literacy. Similarly, the horseshoe-shaped print studio is the heart of the building and occupies a double-height space full of visual interest. However, Castle Mills had previously been chopped up into cellular offices, so the plan was opened up and attics were removed to reveal the structure of cast iron posts and timber trusses.

Underneath them are printing presses with cast iron wheels, tiers of drying racks, polished lithography stones and of course the rich mineral scent of printing ink. Yet as a working environment I had a couple of reservations: one is the lack of a strong connection between the working area and public spaces. Unfortunately, just like Dundee Contemporary Arts, the printmaking studio sits on a different level to the café and galleries, so it’s difficult to watch the printmakers at work. The other is the control of light in the print studio: when I visited, sunshine blasted down from the rooflights onto the platens of the printing presses. The building’s public side includes a shop and two galleries, each of which has a different character. One is a tall northlit cuboid, the other a toplit gallery with a central well which reveals the shop below. The café spills out onto a south-facing terrace, sheltered between the building’s two wings. It feels like an oasis, screened from the traffic on Dundee Street and the construction work going on elsewhere in Fountainbridge, and facing outwards is an extension clad in white glazed brickwork. Conservation work included cleaning and repairing the multi-coloured bricks from Niddrie, and refurbishing the original sash and case windows.

Although it’s not obvious from street level, the roof was entirely reslated using Burlington Blue slates, and the trusses were repaired to deal with extensive rot. Beyond the entrance hall lies a range of offices and meeting rooms whose former Edwardian plushness has been replaced by a spare aesthetic of raw brick, plain plaster plus grey resin and screed flooring. Modern interventions are marked out in richer materials: polished brass handrails, bronze ironmongery and white marble thresholds. The tones are contemporary yet sympathetic to the existing fabric, and that highlights the slow cycle of architectural trends. A century ago, brass and bronze hardware were the norm. Manmade materials like bakelite and ebonite (the latter once made at Castle Mills) were tried, then aluminium emerged after the War. Stainless steel was pioneered by D-Line during the 1960’s, and now hardware manufacturers such as FSB and Samuel Heath offer antique bronze and aged brass finishes. What comes around… Castle Mills’ history has been been worked into the scheme through three permanent artworks. Page\Park collaborated with Calum Colvin to create the “EPscope”, a cross between an episcope, kaleidoscope and periscope which offers a glance from the ground floor café into the first floor printmaking studio.

Colvin also created murals which lined the façade while the building was derelict. The decorative metal gates which screen the main entrance on Dundee Street were designed by Rachel Duckhouse, doubly inspired by the rollers of rubber calenders and printing presses. The roller motif creates powerful graphic patterns which express for the new entrance what the Edwardian cast iron gates on Gilmore Park say about their own time. The third artwork is Mark Doyle’s “Catalogue Wall” which portrays the many things North British Rubber once made. It consists of low relief panels cast in glass fibre-reinforced concrete which is crisp and smooth, in contrast to the rough, weathered faces of the Niddrie bricks. All three are exemplary installations, where the client, architects and artists collaborated. At a cost of around £6.5m for a floor area of 2675 sq.m., Page\Park have realised a great deal of value from the existing building and made it work hard for Edinburgh Printmakers. Rubber is no longer made by the North British and the Cavalier isn’t laughing any more, but a new generation will get the chance to see a different kind of product emerging.

|

|