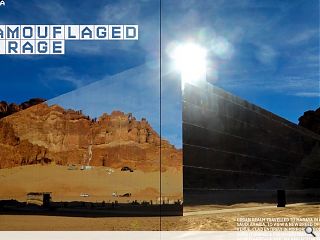

Maraya - Camouflaged Mirage

24 Apr 2019

Urban Realm travelled to Maraya in Al-Ula, Saudi Arabia, to view a new breed of concert venue. Clad entirely in mirrors across two sides it brings a fresh perspective to the UNESCO World Heritage Site. We reflect on the lessons learned from a dazzling desert showpiece.

Rising from the sands of the Arabian desert a shimmering new temple of culture has appeared amid the dunes, promising to slake the thirst of travellers with a packed programme of cultural events throughout the Winter at Tantora festival. Coming ahead of David Chipperfield’s Edinburgh concert hall Al Maraya faces similar challenges in marrying cutting-edge acoustics and design within an area of exceptional beauty centred on the of Mada’in Saleh or ‘Hegra’, Saudi Arabia’s first World Heritage site. These challenges presented a tricky foundation for its Italian designers who had to overcome extremes of climate and isolation to deliver a concert hall with a truly global appeal.

Al Maraya, Arabic for mirrors, is a new concert venue situated in the desert town of Al-Ula, deep in the heart of a dramatic desert landscape which has been likened to a cross between Petra and the Grand Canyon. Conceived as an actual giant mirror that reflects these surroundings the concert hall stands as an exemplar for sustainable development in a region determined to establish itself as a global tourism destination, as mass tourism continues its remorseless advance through the world’s few remaining attractions that remain off the beaten track.

Florian Boje, managing partner of architecture studio Gio Forma played a key role in making this happen, he told Urban Realm: “We were struggling because once you’re on site it is very difficult to say we should build something here. Our first reaction was we shouldn’t do anything, it is too beautiful. This gave us the idea to come up with a mirror which not only reflects light but serves as a place of cultural exchange. There is no present, just past and future, the reflections are so strong that we can still see them.”

Cloaked from its surroundings the Al Maraya building stands as an extension of the surrounding landscape. Extending views of its gorge setting on two sides, the building takes the opposite approach to the likes of Bilbao’s Guggenheim Museum by establishing a building not to define Al-Ula internationally, but to be a hall defined by its locality, appearing almost like a mirage in the desert so unlikely is its appearance.”

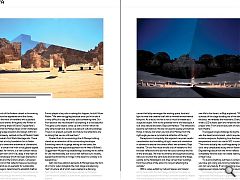

Split into three distinct elements Al Maraya takes the form of a ‘mirror cube’ alongside the main stage and adjoining ‘tent’ structure, all of which were created in a dizzying four months of activity following a decree by the Royal Commission to create a cultural event space and ‘destination’ theatre.

Less architecture and more an example of land art the concert hall ably rearranges the existing space, land and light to meet the creative brief with a minimal environmental footprint. As a result, the hall is not so much a theatre as a sculptural object. Akin to the polished mirror of a telescope, it is at once natural and alien, Boje commented: “The reflections become symmetrical. We are not used to seeing symmetrical things in nature and when you look at Al Maraya from the right angle you see a symmetrical reflection of the sky.”

Deceptive in its simplicity this approach required careful consideration and modelling of light, views and orientation in advance to ensure the correct effect was achieved. Boje recalled: “On our first recce we did a lot of research to find the best reflections and see how we could continue the line of the landscape. We tried to enhance and augment existing nature so we took the sand dune and carved out the stage, exactly as the Nabataeans did, they carved their buildings from the surface of the sand. It’s not just reflecting the outside.”

With a video exhibit by Cultural Spaces and ‘kinetic art’ by Leva and Todo this technology combines to create an audio-visual spectacle which helps draw the audience deeper into the landscape. Incorporating this digital projection technology as an intrinsic component of the main hall brings new life to the desert, as Boje explained: “We carved the surfaces of the stage building out of the sand dune and on the back, we revealed the mountains. Every evening the kinetic LED screens open and reveal the nature which we project onto. From a technical point of view, it’s a very high-tech theatre.”

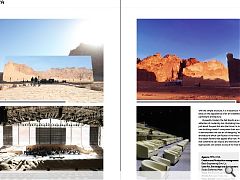

The biggest single challenge facing the designers was the desert environment, which required an equally extreme response. Explaining how the team helped mitigate temperatures which can rise to 50C in summer. Boje said: “The mirror actually has a self-regulating climate. We did a very complicated study with an Italian firm (Black Engineering) about how the mirror reflects heat. It’s completely flat and does not create heating zones so it is not a major issue.

“To build something out there is complicated because you have got a long way to bring materials and the weather can rain very heavily. It’s an interesting issue of how to organise even simple matters such as sourcing paint.”

Eschewing the golden Quweira sandstone, which is piled high across the landscape in gigantic outcrops of rock Each mirror takes the form of an aluminium and plastic sheath, a material which proved to be very easy to use. Combined with the simple structure, it is in essence a wall, the building takes on the appearance of an art installation as much as permanent architecture.

Avowedly modern the hall stands as a conscious reflection of modernity too, illustrating how Al-Ula is not just about the past but also the future. In showing how new buildings needn’t overpower their surroundings it demonstrates the lost art of designing ‘wallpaper’ architecture which can flourish in the most unlikely of spots like desert flowers that appear after rain. Moreover, it shows that constraints can inspire and that one of the world’s best kept secrets can remain as one of its most beautiful places.

|

|