Aberdeen Music Hall: Concerted Effort

24 Apr 2019

Aberdeen Music Hall sits in harmony with its surroundings once more following a much-needed overhaul at the hands of BDP. We sound out the team behind its delivery and assess the wider implications for efforts to rejuvenate Union Street. Photography by David Barbour

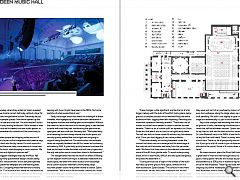

Aberdeen’s Music Hall, situated in in the heart of the city in Union Street, has been tuned up at the hands of Aberdeen Performing Arts (APA), Kier Construction and BDP as the lynchpin of wider efforts to reinvigorate the ailing thoroughfare but is a £9m makeover sufficient to overcome deficiencies in a venue which had become unfit for modern audiences?

Designed by local architect Archibald Simpson in 1822 as the Assembly Rooms, a private members club for the city’s upper crust, the A-listed venue was only converted to a concert hall in 1859 and had turned its back to the street throughout this period as a result. This fundamental issue posed the greatest challenge to a design team sandwiched between the competing desires of accessibility and heritage conservation. To see how this circle was squared Urban Realm paid a visit to see how an introverted space designed to keep the public out has now become an emblem of openness and accessibility.

APA chief executive Jane Spiers has been the driving force behind these changes, having long been frustrated by a front portico that acted more like a barrier than an entrance. The resulting changes are significant but, in deference to the strict conservation remit of Historic Environment Scotland (HES), largely invisible. Indeed for harried shoppers scuttling past a compromised pavement sandwiched between steps and a bus stance the most immediate change is a gentle ramp offering step-free access. It is joined by a Sesame Access Lift, a high-ticket item that grants equal access to everyone, functional enhancements to which are added more flamboyant touches such as a video wall which animates the space in front of a retained alcove – again mandated by HES.

Standing proudly in the centre of a now clearly defined reception hall, visitors are no longer greeted by an empty space. Spiers said: “One of the straplines for the development was ‘A new hall for a new generation.’ This is a special space within the city, it’s not just a concert hall, it’s a civic space. People who live here take real ownership of it, you’d be hard pressed to find anybody in the northeast who hasn’t got a story to tell about this building.”

Addressing the fixed gaze of Queen Victoria, whose depiction in plaster takes centre stage once more, Spiers added: “We actually looked to take out the whole back wall but HES wouldn’t support it because of concerns about the niche. The proposal was to put in new lintels, but the wall was made out of rubble and bits of timber, there was no way it was going to take the load. Kier came up with the idea of inserting a series of steel needles into the wall to transfer the load. We could then take out the intermediate section of the wall and pour concrete. We ended up with a 900mm deep concrete lintel. We did say to HES we’d have to take it down and rebuild it in dry lining, but they insisted.”

In addition to benefitting the public a cascade of circulation and layout improvements has also aided staff, who have been rescued from a series of dungeon-like windowless rooms now replaced by bright and airy offices at the front entrance - creating a more secure environment while also opening up space. Spiers explained: “The external vestibule was a simple austere space with small doors in the corners, presumably to be manned by someone in uniform. It was an exclusive environment and ran completely contrary to the ambition to make the hall as open and permeable as possible.”

This was the brief which was handed to project architect Bruce Kennedy, who faced the challenge of realising such goals within a relatively constrained budget in a building in which no-one quite knew what they would uncover once construction began. Kennedy said: “The initial brief was about addressing audience comfort, environmental concerns, operational improvements and accessibility. All the public spaces were incredibly congested in a series of discrete rooms. We’ve ended up with a scheme where all the public spaces are effectively accessed off the promenade. We opened up a new arch to create a direct link to the balcony and basement and a new door between the round room and the promenade. It looks quite trivial, a simple door, but the engineering for that was quite complex.

“While the clients were aware of their responsibility to the A-listed building it just wasn’t working for them with outdated facilities and lack of seating. It wasn’t about replacing services but delivering the functional brief. What we’ve done is reasonably sustainable by retaining everything except the electrical and lighting systems, which were life expired.

If the front porch was where the hall’s problems began it was not unfortunately where they ended, as Spiers revealed: “You would never build a concert hall today without a foyer for people to meet and mingle before a show. Previously we just had a hall where people queued. Now we’ve opened up the ground floor as a café and crush bar. You also wouldn’t build a concert hall with only one big auditorium. We’re limited in what we can do here but we’ve created two new studio spaces, so we now have somewhere for schools and the community to use.

“At a time when people are shopping online and out of town, we’re part of a plan to find imaginative and creative ways to bring people back into the city centre. It’s much more of a 24/7 building and there are many more reasons to come here whether that’s for lunch, workshopping or music sessions. We have an exhibition and digital art space as well.”

One of the biggest challenges faced by the Music Hall came in undoing many questionable design choices dating from a prior 1980s ‘refurbishment’ which saw pillars painted marble, gaudy patterned wallpaper and overbearing plate brass chandeliers. Consigning these interventions to history Spiers continued: “Our approach was where we can restore we will but where we need to make a new intervention we will do something that is quality, with a bit of a wow factor and is in keeping with how it might have been in the 1800s, Not some pastiche of what people think it was.”

Sadly, the budget would not stretch to undoing all of these mistakes, most egregiously a former ballroom demolished in the eighties to allow new rooftop plant to be installed. Without the means to return the room to its former glory, it was decided to settle with what they had, transforming the space into an open plan café and crush bar. Kennedy said: “We looked early on at restoring the two-storey volume as a studio space, but we very quickly realised that the budget was not going to support taking the plant out. The construction cost estimate when we originally tendered was £4.5m, based on fundraising estimates by APA. It grew fairly quickly because to achieve the brief we did need to take the toilets out and free up space and the only real option was to move them down to the basement.”

This reorganisation has had the knock-on effect of freeing up two adjacent rooms serving as a dedicated restaurant and studio space, the latter with direct access to the backstage and a custom acoustic treatment.Unfortunately, large recurrent plaster cracks have proven trickier to banish. Speirs commented: “We’ve had to fix the plaster cracking four times and now we’ve just come to accept that we’ll have to leave it to the end of the defects period.”

These changes, while significant, are like the tip of a far bigger iceberg with the bulk of the effort taking place below ground, a complex process which entailed lifting the entire auditorium floor, digging down and replacing. Revisiting this mammoth operation Kennedy recalled: “There was a lot of hidden structural work needed in order to deliver discreet benefits. There is a lot of rubble upfill, an aqueduct on Union Street and the area it sits on used to be significantly lower. The hall was built on loose rubble fill without any foundations at all. Once you start digging it can cause problems.

“There was already an existing basement under the concert hall which we could enlarge and the advantage of that was we could excavate well away from the perimeter walls. We found out there were no foundations underneath some of the 4ft thick granite walls. To avoid underpinning those, which is technically difficult and also quite dangerous, we pulled the basement in.”

Tucking services out of sight in the bowels of the build has freed up prime ground floor space, centred on the main auditorium. Spiers added: “The colours in here were unbelievable, we had lime green wallpaper and stripes/stencilling across the ceiling. We stripped it all back to reveal the Strachan murals. It makes them feel right, whereas before they were just part of an overbearing colour scheme. We even had wallpaper along the stage where we now have built panelling. We built it out slightly to give a slightly bigger stage but aesthetically it’s just so much better.”

Key to the changes was ensuring that the hall sounds as good as it looks, maintaining the distinctive acoustics for which the hall has achieved renown. Speirs said: “We all tend to say that our hall has the best acoustics however composer Sir John Barbirolli said in the 1960s it had the finest acoustics of any hall that he’d heard. There’s a lovely warm and sharp sound here. There is a lot of pomposity around acoustics but if you go to a lot of concerts you do have an ear that is attuned to the sound. Some of it comes down to personal taste.”

No mere museum piece the Music Hall must weather a great deal of wear and tear brought about by concert-goers, heavy goods vehicles and outsize equipment, happily exacerbated by a 20% jump in audience figures in the weeks since the hall reopened. These figures bode well for an ongoing city centre masterplan, also overseen by BDP, which sees Aberdeen seek to finally regain the initiative by realising long-held ambitions for Union Terrace Gardens, providing a point of unity around which the city can coalesce.

|

|