Tenement Maintenance: Stone broke

23 Apr 2019

Year’s of neglect in the maintenance of Scotland’s tenement heritage have come to a head with a backlog of repairs which threaten to swamp owners and local authorities alike. Architect John Gilbert look at how we came to be in this situation and what can be done to kick-start much needed repairs.

The Scottish tenement is an integral part of the urban landscape north of the border with these iconic stone buildings forming the dense centre of almost every town, often with shops forming the ground floor. The tenement allows Scots to have good quality urban housing at a scale which works for local communities. It can also be energy efficient and adaptable.

But tenement maintenance is a growing problem. A recent report from Glasgow City Council suggested that the final bill for repairing these buildings could be as much as £2.9 billion in Glasgow alone. In response, a Scottish Parliamentary Working Group has made proposals for a radical change in legislation that would pave the way for improvements. But why has this problem occurred?

Unlike the position in England and Wales where people lease flats and are effectively long-term tenants, in Scotland people own flats outright. Tenement owners need to work with their other co-owners to carry out repairs - there is no head freeholder arranging repairs using regularly paid service charges to cover the cost of works.

However, getting agreement to carry out a common repair is fraught with difficulties. The law requires a majority of owners to agree to work but owners often do not know even who their co-owners are, a situation that is getting increasingly common as private rented levels increase in flatted properties. Then a lack of a maintenance culture combined with increasing levels of low-income owner-occupation conspire against those owners seeking to do the right thing.

A number of physical issues add to the increasing decay:

• Climate Change: in the last 30 years, Scotland’s winters have become increasingly wetter. Stone walls which are meant to dry out in between showers, are becoming saturated. The problem is exacerbated when overflowing gutters and downpipes focus water onto the face of the stone. Eventually this leads to the rotting of original timbers which are embedded into to external stone walls. Joist ends, timber Bressumer beams at oriels and bays and timber safe lintels above windows are all at risk.

• Previous repair programmes: in the 1980s, grants of 90% were given to encourage tenement repairs. Although this saved many tenements, repairs to and repointing of stonework was carried out with cement and decayed stone was made to look good by being coated with a material called ‘linostone’. These repairs prevented the stone walls from drying out. Instead moisture was trapped within the stonework leading to frost attacking the stone and damaging it yet further. In addition, the high level of grant led to owners thinking that the Council would always be there to look after the common areas.

• Georgian Edinburgh: Craigleith stone in the NewTown has held up very well and despite being older, has weathered better than stones in the West. This may be a result of material costs as feu’d developments often used a cheaper stone like Binny Sandstone which has not weathered so well. The other main risk in Edinburgh is secret and parapet gutters which are hidden from view. The double pitched wider tenements required a central valley. Overflow outlets are often blocked or inadequate is size to cope with heavy showers.

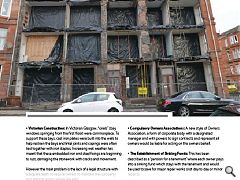

• Victorian Construction: In Victorian Glasgow, “oriels” (bay windows springing from the first floor) were commonplace. To support these bays, cast iron plates were built into the walls to help restrain the bays and lintel joints and copings were often tied together with iron staples. Increasing wet weather has meant that these embedded iron and steel fixings are beginning to rust, damaging the stonework with cracks and movement.

However the main problem is the lack of a legal structure with adequate teeth to require owners to maintain their property and enforce repairs where required. The Scottish Parliamentary Working Group on Maintenance of Tenements is developing proposals to put before Parliament to address this problem. The main changes proposed are:

• Five Yearly Inspections: to make it compulsory for every tenement to have a full inspection every 5 years. This would be tied in to the Home Report that is required for the sale of a flat. The report would place defects in a range of categories from desirable to urgent and immediate. This would at least give owners the knowledge they need to know and plan for future repairs.

• Compulsory Owners Associations: A new style of Owners Association, a form of corporate body with a designated manager and with powers to sign contracts and represent all owners would be liable for acting on the owners behalf.

• The Establishment of Sinking Funds: This has been described as a ‘pension for a tenement’ where each owner pays into a sinking fund which stays with the tenement and would be used to save for major repair works (not day to day or minor repairs).

In the meantime, any owner wanting advice on organising common repairs, can use the website www.underoneroof.scot which is managed by Changeworks in Edinburgh. The website explains the steps owners need to implement when organising repairs, describes the stages step by step and provides technical advice on tenement repairs and maintenance.

Across Scotland, there seem to be widespread support for bringing forward a competent legal structure to prevent the loss of a valuable asset that is a unique part of Scottish cultural life.

Euan Leitch, director, Built Environment Forum Scotland

Communio est mater rixarum – co-ownership is the mother of disputes. Were the Scottish Parliamentary Working Group on Tenement Maintenance to have a motto, this maxim from Roman Law could be it. Convened in March 2018 by Ben Macpherson MSP the working group is an informal grouping of cross party politicians and stakeholders with a declared interest in tenement maintenance. These stakeholders come from the fields of chartered surveying, building, property management, architecture and property law; with the agreed purpose of the working group to “consider and establish solutions to urge, assist and compel owners of tenement properties to maintain their property”. Built Environment Forum Scotland and the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors share the secretariat function.

There are 895,000 properties in Scotland that fall within the legal definition of a tenement – two or more flats divided horizontally and designed to be in more than two ownerships – 37% of the housing stock. While there is a default perception that problems in tenement maintenance apply to more traditional stone buildings of 8+ flats, our research revealed similar challenges in post-war housing schemes where right-to-by has resulted in multiple, often non-resident, ownership; there is also increasing concern that owners of tenements with lifts are ill-prepared for imminent replacement costs.

The necessity for improving the maintenance of tenement properties is established not just from the professional experience of the participants, or from MSPs’ constituency surgeries but by the Scottish Housing Condition Survey. The 2017 report estimates that 50% of properties have disrepair to critical elements, rising to 68% for buildings built before 1919. Recent investigations in Glasgow and Edinburgh put rates of disrepair even higher. Communally owned properties face particular challenges in undertaking preventative maintenance.

The working group commissioned Professor Douglas Robertson’s report, Common Repair Provisions for Multi-Owned Property: A Cause for Concern to give an overview of existing arrangements for tenement maintenance and ask, are the working? The report narrates the incremental approach that successive administrations have taken on the issue, with the nettle never being fully grasped. That said, the standards applied to social housing have made a substantive difference and housing associations now have the best maintained housing stock across all tenures. But even housing associations are facing challenges where they are not the majority owner in a tenement and some are now divesting themselves of properties because of this.

To address these issues the working group published interim recommendations. These recommendations would statutorily require tenements to have:

owners associations

sinking funds (a pension pot for the building)

five yearly inspections (undertaken by a professional with indemnity insurance)

The recommendations are interlinked, each dependant on the existence of the other two with the long term aim of forcing a culture change in ownership responsibilities. The informal consultation closed in March and the response was heartening but robust.

Broadly, consultation submissions are supportive of the interim recommendations in principle with a lot of commendation for addressing such a difficult and pressing issue, with calls from property owners and managers to be brave in the final recommendations.

But respondents have significant questions on how the recommendations would be applied and enforced, how financially disadvantaged owners would be supported and how these actions might affect the property market.

The issue of tenement repair sits amongst a number of connected agendas from climate change and fuel poverty to fire safety. A number of respondents reflected on this and on the higher standards of enforcement undertaken in North America and some European countries.

The Hackitt Report makes recommendations about owner’s duties of responsibility for safety and maintenance in communally owned buildings and the benefits of a digital record which, while focused on buildings of above 10 storeys in England, should have lessons for Scotland. This in itself connects to wider agendas about access to data related to land and property ownership which are being currently debated. Registers of Scotland’s ScotLIS facility is something the working group are looking at as a potential repository for relevant property information.

In our search for evidence on the need to address the complexities of communal building maintenance we have gathered many individual experiences, some of which have had a profound impact upon owner’s health. Sometimes it is from the physical housing condition but often from from the high levels of stress experienced due to uncooperative owners. It can therefore be somewhat galling to have building disrepair statistics referred to as ‘maybe just a leaking tap’.

The Scottish Parliamentary Working Group on Tenement Maintenance is now identifying questions that have been raised from the consultation on how the three recommendations would function. There was general agreement at the most recent meeting that behaviour change arises primarily from legislative imposition – seatbelts and smoking are often referred to – but it was acknowledged that there will need to be support provided to meet any new requirements. This support could include advice and guidance, as well as financial assistance.

The commitment of the Scottish National Party, Scottish Conservatives, Scottish Labour, and Scottish Green Party members of the Scottish Parliament to the working group is key to any progress, it cannot be a one party issue. There is no quick fix and sustained pressure is required for success. It is often stated that 80% of the homes we will be occupying in 2050 are already built: maintaining, reusing and retrofitting our existing housing stock is one key way of reducing Scotland’s carbon footprint.

Full details of the working group can be found on BEFS website.

|

|