Schupp & Kremmer: Ruhr Tour

23 Apr 2019

Mark Chalmers embarks on a tour of Germany’s Ruhr region to take in the legacy bequeathed by Bauhaus-trained architects Schupp & Kremmer, who transformed the area with collieries and factories. The most famous of these, Zollverein, is now a world heritage site - a stark reminder of the gulf in regard for our own industrial legacy.

Over the past decade, I’ve made several trips to the Ruhr valley in Germany. The first began at Zollverein in Essen, a monumental colliery and cokeworks complex which is now a world heritage site. I also took in the Sinteranlage in Duisburg, a rusty hulk which sat in the middle of a wilderness, and Zeche Hugo at Gelsenkirchen, one of the final collieries in the Ruhr to close.

During that trip, I became fascinated by the work of Schupp & Kremmer, the architects who designed Zollverein and Hugo. The buildings which wrap around the functions of a colliery – winding coal up the shaft, washing, grading, then despatching it – could easily be classed as non-architecture. After all, “architecture” is an artificial construct, the result of a silent agreement amongst the authors and journalists who have the power to define it.

Do industrial buildings count as architecture? Fritz Schupp and Martin Kremmer spent their careers working as industrial architects, which some might think is a contradiction in terms. They specialised in collieries, a building type which has all but disappeared now there is no deep coal mining in Western Europe.

Schupp & Kremmer founded their practice exactly a century ago in 1919, just after the Great War ended, in the same year the Bauhaus was founded. Their architectural roots lay in the Expressionism which flowered in Weimar Germany during the 1920’s, but its reticulated and buttressed brickwork soon gave way to functionalism. The Bauhaus approach was particularly suited to industrial buildings, and Schupp & Kremmer recognised that.

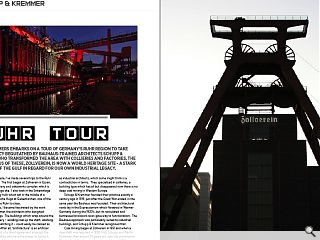

Coal mining began at Zollverein in 1851 and when a new shaft was required in 1928, Fritz Schupp and Martin Kremmer, then around 30 years old, won the commission. The shaft, pit head and connected buildings of Zollverein XII were completed in 1932: with an output of 12,000 tons of coal each day, it became the world’s most productive colliery.

The silhouette of Zollverein XII, a doppelförderung (double winding tower), soon became the symbol of the Ruhr. Traditionally, the back legs of headgear are inclined to resist the forces of the winding ropes, cages and minerals travelling up and down the shaft. In the case of Zollverein and its counterpart Barony in Ayrshire, all four legs are splayed outwards. The rest of the complex consists of austere, cubioidal buildings clad in brickwork and patent glazing.

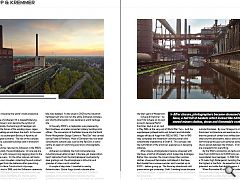

Schupp & Kremmer returned to Zollverein in the 1960’s to build a coking plant, the Zentralkokerei. On one side are the coaling towers, with conveyors zig-zagging down to the heads of the coke ovens. On the other side are rail tracks along which coke cars travelled, collecting the end product as it was discharged from the batteries after quenching. The overall effect is like a Constructivist cityscape.

Zollverein XII shut in 1986, and the Zollverein cokeworks followed in June 1993 when German steel production was cut sharply. Its owners, Ruhrkohle AG, tried to sell the cokeworks as a job lot to the Chinese, but the deal fell through – so it sat derelict for nearly a decade while its fate was debated. It was saved in 2001 by the industrial heritage trust who now run the entire Zollverein complex, and shortly afterwards it was declared a world heritage site.

In the early 2000’s, a masterplan was prepared by Rem Koolhaas, who later converted colliery buildings into offices. The conversion of the Boiler House into the North Rhine-Westphalian Design Centre or “Red Dot” was carried out by Foster & Partners. Most of Zollverein has now been converted to cultural uses, such as the Red Dot, a visitor centre, an open air swimming pool and a choreography centre.

Zollverein is probably the most comprehensive industrial preservation project in Europe, yet preservation hasn’t detracted from the Zentralkokerei’s authenticity: steel gratings rust, the atmosphere is still acrid, and granules of coke crunch underfoot.

A couple of days later, I travelled to nearby Gelsenkirchen. Zeche Hugo closed a decade after Zollverein, and it was built much later, too. The 1960’s spareness of its umber-brown brickwork, the strip windows, black-painted steelwork and white tiles exemplify the rationalism which many German architects adopted in the later years of Modernism.

Schupp & Kremmer – by now Fritz Schupp on his own account, because Martin Kremmer died in an air-raid in May 1945, at the very end of World War Two – built the waschekaue (pithead baths and lockers) and lohnhalle (wages offices) at Hugo from 1952 to 1955. Then in 1961 they completed the förderturm (winding tower) and schachthalle (headworks) at Shaft 8. This complex was the culmination of the practice’s experience in designing collieries.

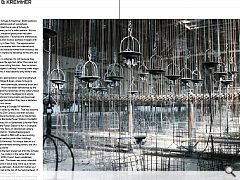

After closure, photographers became obsessed with the Kaue, a hall full of baskets which looked like birdcages. Rather than canaries, the miners stored their outdoor clothes, shoes and flammable contraband in the Kaue. Each basket has a unique number, and I counted up to 5000 ... before giving up. The Kaue lay abandoned until preservation got underway: Shaft 2 winding house became the “Little Museum”, a venue for performances, dinners and book launches.

A couple of years after photographing Zollverein and Hugo, I returned to the Ruhr to visit Lohberg, a mining town outside Dinslaken. By now I’d begun to study Schupp & Kremmers’ architecture and examine its sources. I realised that the panels of clinker brick infilled between rolled steel columns and beams, were a direct descendant of the half-timbered houses built centuries earlier with brick and stucco panels between the timbers. In architecture, there are precedents for everything.

By the 1950’s, production at Zeche Lohberg 1/2 had risen from 4,000 tons to 13,000 tons per day, and that necessitated new headgear. In 1953 Fritz Schupp designed a 70 meter high fördergerüst (winding frame) which was the highest in the Ruhr. He asked for his design to be patented, and while that didn’t happen, it remains unique.

When Ruhrkohle AG shut Zeche Lohberg in 2005, the town and the colliery both lost their purpose. The colliery will eventually become the “Kreativ im Quartier Lohberg“ – following the example of the “Creativ Quartier Fürst Leopold” in nearby Dorsten, another colliery although this time not designed by Schupp & Kremmer. Both locations now host events, exhibitions and art workshops.

By now, I realised that the re-use of Schupp & Kremmer’s collieries was part of a wider pattern. Across the developed world, industrial production has been converted into art production. Factories and warehouses have become galleries and studios; perhaps it began with Andy Warhol’s Factory in New York. The appropriation of industrial buildings resonates with the materials and techniques which artists have borrowed from industry; the collieries also form an impressive backdrop to the arts, and therein lies a paradox.

If you find beauty in collieries, it’s not because they were designed to please the eye, but rather they were put together to serve an over-riding function. Few ex-miners care about how photogenic Lohberg’s winding tower might be today. In their terms, it was beautiful only while it was working.

The sense of artistic appropriation was strengthened by a visit to Zeche Schlägel & Eisen, where Schupp & Kremmer designed a new boilerhouse, entrance block and coal washery in 1938. Much had been demolished by the time I visited in 2011, and the remainder of the colliery faced an uncertain future. The Shaft 3 headgear and engine house are listed as historical monuments and have been preserved by a heritage foundation: they have a tentative future as a music and art venue.

Once again, something of Schupp & Kremmer’s architecture has been saved by the Arts. That has become a defining theme of the 21st Century, and that includes the highest profile cultural buildings, such as Tate Britain in London (the former Bankside Power Station), the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art in Gateshead (a former Rank Hovis flour mill) and the Power Station of Art in Shanghai.

In another part of the Ruhr, an abandoned colliery sits near the town of Hamm. Steinkohlenbergwerk Heinrich-Robert was rebuilt in 1953 with a new winding tower, heapstead, coal washery and other buildings designed by Schupp & Kremmer. Its unique feature is a hammerkopfturm (hammerhead winding tower), one of a handful left across the world.

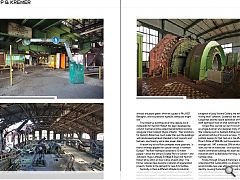

Heinrich-Robert is the best-preserved of all the Schupp & Kremmer buildings I’ve visited, in the sense that since closure in September 2010 it hasn’t been vandalised, refurbished or converted. The tower was never intended to be a public space, and it was a long climb up a narrow steel staircase into the darkness. Around 50 metres up, I emerged into a large hall at the top of the hammerhead. It was surprisingly bright and colourful.

The chequerboard of cream and burgundy tiles on the floor was still overlain by a layer of coal dust. The winding engines, among the most powerful in the Ruhr coalfield, lay intact despite finishing work several years ago. Their shrouds are jasper green, which at a guess is RAL 6021 Blässgrün, and the powerful hydraulic brakes are bright red.

The locked-up buildings are a time capsule, but a masterplan for Heinrich-Robert has been developed by a Dutch-German practice called DeZwarteHond working alongside Urban Catalyst Studio of Berlin. Their ambitions for Heinrich-Robert are much wider than just the buildings: with landscaped parkland intended to host concerts and festivals, plus forestry and a solar power station.

A recent trip to the Ruhr prompted more questions. Is there a limitless appetite for cultural venues in northern Europe? The Ruhr metropolis extends to 12 million people – about the same as Greater Paris or London – and Zollverein, Hugo, Lohberg, Schlägel & Eisen and Heinrich-Robert all lie within an hour’s drive of each other. The former collieries have become a network of regeneration projects, thanks to the demand for new Arts facilities.

Secondly, is there a different attitude to industrial conservation in Germany? In Scotland we have an active Historic Environment Scotland with industrial specialists such as Mark Watson and Miles Oglethorpe who advise on the conservation of industrial buildings. However, with the exception of Lady Victoria Colliery, the remnants of coal mining aren’t coherent. Scotland’s last working colliery was Longannet, and the recent demolition of the Castlebridge shaft destroyed most of what remained there.

In Egon Riss, we had our own Fritz Schupp. Riss was an emigré Austrian who designed many of Scotland’s post-War collieries such as Seafield, Rothes and Monktonhall, yet almost nothing of his work survives. There are political reasons for that, tied up in the aftermath of the Miner’s Strike of 1984-85, but the economic forces are stronger still. VAT is levied at 20% on refurbishment work, but not on newbuilds – and business rate relief on vacant commercial buildings has been decimated. Empty industrials don’t lie abandoned for long, regardless of their heritage value.

Finally, through Schupp & Kremmers’ legacy, I came to understand that sustainability is a broad kirk. The collieries accommodate new uses while sustaining their previous identity, re-using the building fabric, and supporting new jobs to replace those lost when coal died. By conserving the collieries the Landeskonservator and state government in North Rhein-Westphalia are actually involved in an enormous sustainable architecture project.

|

|