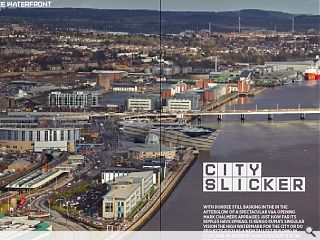

Dundee Waterfront: City Slicker

16 Jan 2019

With Dundee still basking in the in the afterglow of a spectacular V&A opening Mark Chalmers appraises just how far its ripples have spread. Is Kengo Kuma’s singular vision the high watermark for the city or do projects such as a new tallest building in Scotland by Invertay Homes suggest it is on the crest of a new wave of development?

When the press pack descended on Dundee for the opening of the V&A, many sought the city’s identity in the one thing they knew: jute. There isn’t much to see of the jute industry nowadays; the last of its derelict mills, Lower Dens Works, recently reopened as Hotel Indigo. However, Dundee only became the world capital of jute thanks to the Tay.

Before jute, the city’s wealth came from the river, thanks to mercantile trade, shipbuilding and whaling. Even in those days, Dundee was a global city which traded with the Hanseatic League and Baltic ports. It took shipments of flax from Archangel and jute from what became Pakistan and Bangladesh – but Dundee’s notoriety began with the whalers.

Herman Melville was obsessed with whaling (think of Captain Ahab’s life-and-death struggle with Moby Dick) and in his novel Billy Budd, Melville’s title character is impressed by a Dundee merchantman, who wears “big hoops of gold in his shapely ears and a Scotch Highland bonnet atop his dancing yellow curls”. In Melville’s day, the world’s whaling ships were built and engined on the Tay, and Billy Budd sailed on a fictional vessel owned by a Dundee shipowner.

Whale oil from the city’s rendering factories was later used to soften the tough fibres of the jute plant, and its shipyards adapted to the textile trade by building clippers and jute liners. Maulesden, built by Alexander Stephen & Sons at the Panmure yard, was the fastest clipper ship of all time. Later, the Caledon yard built ferries, cable ships and dozens of cargo liners for Alfred Holt’s Glen Line. The site now refits and decommissions North Sea platforms, using the biggest quayside crane in Europe, an 875 ton giant.

The waterfront was crucial to Dundee’s growth, but as seaborne trade and shipbuilding drained away, its re-development became pivotal to the city’s future. The first waterfront plan of 1986 saw the creation of a Tesco store on Riverside Drive, followed by Discovery Point, then the Victoria Dock regeneration scheme of 1993 which evolved into City Quay. Ten years later, the Apex City Quay hotel opened nearby and the Central Waterfront regeneration plan emerged in 2001.

Prospect Magazine’s Autumn 2009 issue described the waterfront’s new shape as it began to emerge, then in 2014 I wrote that, “The ultimate aim is to create a new grid of streets around a landscaped square – but the other buildings could be seen merely as a setting for the V&A.” I was wrong, because the converse is true: the V&A was just a pretext for the regeneration of the waterfront.

Speak to Dundonians, who express pride mixed with gentle puzzlement that Kengo Kuma was flown halfway around the world to design a museum, and it’s clear some don’t understand how the hidden machinery of the architectural world enabled that to happen. Dundee City Council has done a good job of communicating how the regeneration will work and what it seeks to achieve, but not everyone attended the public consultations, read the newspaper articles nor attended the exhibitions…

Recently, letters to the Dundee Courier became strident about the construction work on Site 6. “Why are they building ugly office blocks in front of the V&A?” – came the voice from the bars. “They’ll blot out the river!” – shouted old men from their armchairs. Yet the masterplan extrapolates a grid of streets and buildings which a previous regeneration of the 1960’s destroyed.

The masterplan calls for medium-rise blocks clad in masonry, and Site 6 is a typical block with brick piers following a strong vertical rhythm. Buildings facing into Slessor Gardens will be five and six storeys high, and the edges of the Central Waterfront scheme will rise to seven storeys. Site 6’s mottled brown brickwork is a rough match for the Kingoodie and Leoch stones from which much of Dundee was built.

As the masterplan’s Planning and Urban Design Framework notes, “Each development site has been intentionally divided into smaller development plots to increase variety and create a more human scale. Hence avoiding the development of large monolithic and repetitive elevations, for example full facades of curtain wall glazing. Diversity of design and use between plots is encouraged to further breakdown the scale and mass of the sites and to strengthen the vision for a vibrant unique sense of place.”

In fact, the Central Waterfront has adopted a traditional urbanism which James Thomson, Dundee’s City Architect a century ago, would recognise and which Jan Gehl, author of Life Between Buildings, would applaud. The waterfront’s green lung, Slessor Gardens, projects out from the building line of the Caird Hall providing an outdoor concert venue and active focus for the waterfront. It’s also a ghost of Thomson’s original waterfront plan of the early 20th century, which planned a huge civic centre on the same site.

When Charles McKean’s “Lost Dundee” was published, I bought the book and read it to pieces. Yet McKean’s book encouraged nostalgia for a waterfront that was long gone. People much too young to remember the Royal Arch suggested it should be rebuilt, and perhaps the Earl Gray and King William Docks should be exhumed, too. Telford’s Beacon has been restored, but the “good old days,” in fact, were not so good.

I remember Paladini’s derelict car showroom at Craig Harbour, the decaying Tay Hotel which stood abandoned for 20 years, and the state into which the Olympia Leisure Centre had fallen before it was demolished. Much has changed over the past few years, and of course that makes people uneasy – but the new waterfront has brought tourism, and with that a demand for hotel beds which would have been unimaginable twenty years ago.

Although the Central Waterfront masterplan hadn’t begun to be implemented, regeneration had already begun in 2003 when the Apex City Quay hotel opened. It was followed by the Malmaison which occupies what was once Mathers’ Hotel, and a newbuild Holiday Inn Express which sprung up to the east. Now the waterfront is circled by a ring of hotels including Sleeperz, a forthcoming Marriott and Apex Hotels’ future plans for the old Custom House.

Dundee attracted them for a couple of reasons. Historic under-investment left gaps in the market waiting to be filled, and the masterplan opened up development opportunities close to the city centre. Speaking to property agents, historically there was too much low-quality floorspace in the wrong areas, hence the city earned the reputation for low yields. New floorspace being built on the waterfront meets a pent-up demand for hotel beds, as well as Class A office space for financial services, digital media and the public sector.

To understand how the hotels fit into the masterplan, it’s worth taking the train to Dundee. Sleeperz is a modern hotel set above the remodelled railway station, but in the grand tradition both of Victorian railway hotels and Air Rights buildings of the 1980’s. The new station was designed by Nicoll Russell Studios and its vaulted ticket hall expresses the giant steel arch which spans the tracks below; a diagrid canopy sits over escalators which lead down to platform level.

The hotel’s fit-out was designed by Space Solutions and follows on from Sleeperz Hotels beside Newcastle, Cardiff and Edinburgh railway stations. Sleeperz opened just after the refurbished station and consists of a colourful, contemporary design scheme and a bar located to maximise views out to the V&A. Sleeperz in this case refers both to what those above the station do at night, and what carries the rails far beneath them.

Just beyond the edge of the Central Waterfront is Dundee’s Custom House and Harbour Chambers. Although not connected to the masterplan, the case for its rebirth is linked to the success of the wider regeneration. Plans for conversion were originally drawn up in 2013, when Urban Realm reported that Dundee would gain its first five-star hotel with a scheme by JM Architects to convert it into a 38 bedroom boutique hotel.

The Custom House is now owned by Apex Hotels who are currently considering options for it. Meantime the building, which was one of the biggest Custom Houses in Scotland, is a landmark on approach to the waterfront. Inside, Dundee Port Authority’s former boardroom retains its ornate oak panelling and a grand fireplace with the crest of the Authority carved onto it. The level of detail gives some idea of the wealth which flowed through the port in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Another prospective scheme sits just off the edge of the Central Waterfront area. A recent feasibility study by Wilson+Gunn looked at the opportunity to create a new Dundee Arena with a capacity of 6000-7000, on the site of the Mecca Bingo hall. The bingo hall in turn replaced Green’s Playhouse, once a 4000 seat cinema with an Art Deco tower, and its rebirth would be another boost for Dundee’s night-time economy – but meantime it is just a feasibility study.

Back within the Central Waterfront masterplan’s remit, the most eye-catching idea so far is Discovery Heights, a scheme for Scotland’s tallest building which was recently announced. It’s intended for Site 12, which sits on arguably the most prominent site on the waterfront, beside the Tay Road Bridge landfall and along from the V&A. A CGI animation shows a 39-storey tower plus podium block, which would house a five-star hotel, conference centre, luxury flats and a Sky Bar.

However, Dundee City Council has already agreed an exclusivity agreement with Dawn Developments, and Keppie Design recently lodged a proposal of application notice on their behalf. Given that, plus the height limits set out in the Masterplan and the challenges that the Beetham Group had with their still-born 40 storey tower at Edinburgh Harbour over a decade ago, it’s fair to say that Discovery Heights is highly speculative.

By contrast, the furthest advanced construction works are on Site 6, where Alimak lifts are currently climbing the facades to complete the brick cladding and curtain walling on a block designed by Cooper Cromar. This will consist of over 80 apartments across two six-storey buildings, plus a 150-bed hotel and four floors of open-plan office space. Despite the criticism of those who write Letters to the Editor, it’s a city-scale building which has already helped to reinforce the urban grain of the new waterfront.

We often criticise the tie-up between town planning and economic development, when inappropriate developments are forced through because jobs and investment win over amenity and aethetics, but the Central Waterfront is an example of how that should be done. Are there issues? Yes: over the past few years, roadworks have travelled around the Central Waterfront with an endless crocodile of traffic cones, and the need to close East Dock Street each time Slessor Gardens hosts a concert is a periodic nuisance.

Yet those are inconveniences rather than failures. The V&A has already succeeded, drawing in around three hundred thousand visitors in its first three months, and approaching half of the planned £1 billion investment has already been sunk into the masterplan area. Dundee is reshaping its city centre in a comprehensive way which nowhere else in Scotland has attempted since the 1960’s, and the results so far are impressive.

|

|