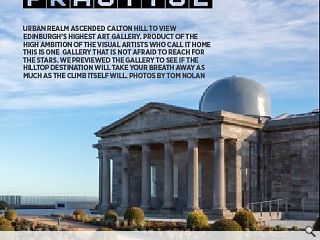

Collective Gallery: Peak Practice

16 Jan 2019

Urban Realm ascended Calton Hill to view Edinburgh’s highest art gallery. product of the high ambition of the visual artists who call it home this is one gallery that is not afraid to reach for the stars. We previewed the gallery to see if the hilltop destination will take your breath away as much as the climb itself. Photos by Tom Nolan

Edinburgh’s City Observatory has embraced the high life with an unmissable hilltop arts venue following restoration of the A-listed William Playfair designed astronomy centre. Disused since 2009 the romantic hilltop complex has been transformed into a lofty exhibition space, offices, a restaurant and shop which weave together the best of art and architecture in a globally important setting.

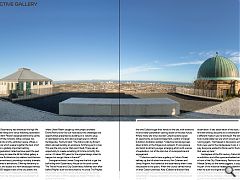

Visual arts organisation Collective have spent the past five years fundraising to make the £4.5m hilltop gallery a reality. by Collective Architecture (no relation) and Harrison Stevens landscape architects, providing a suitably dramatic backdrop for a series of exhibitions. Offering free entry to the passing public and access to a new landscaped terrace, maximising the 360-degree views of the city below, the facility even includes its own restaurant which is partially cantilevered out from the hillside below and referred to as the ‘fourth plinth’.

Appropriately named ‘The Lookout’ it was here in where Urban Realm caught up with project architect Emma Fairhurst to find out more about the challenges and opportunities presented by building on a volcanic plug of solid basalt some 40m above street level in a World Heritage site. Fairhurst said: “The historic plan by Robert Adam advised building an enclosure, fortifying each corner. This was the only corner that wasn’t built. There was an opportunity to create something of its time to fortify this corner, it’s taken 200 years for the original design intent to happen but we got there in the end!”

Georgian architect James Craig was the first to get the ball rolling with Observatory House on the south corner. The Transit House and City Observatory followed soon after before Playfair built the monument to his uncle, The Playfair Monument, as the next corner, preceding the City Dome which followed in 1819 to designs by Robert Morham, city architect of the time.

These structures found themselves in a sorry state by the time Collective got their hands on the site, with extensive rot and water penetration casting doubt on the sites future. Where many saw only a burden Collective alone spied an opportunity, as Susanna Beaumont, curator of Design Exhibition Scotland, recalled: “Collective has always been about artists on the fringes and outreach. It’s progressive and tends to attract younger emerging artists with a sense of exploration, not of the stars but of social practice and engagement.

“Collective used to have a gallery on Coburn Street halfway up the hill when two artists; Kim Coleman and Jenny Hogarth, first looked at the observatory when it was inaccessible to the public. When the council served notice on their Coburn premises. Kate (Collective director Kate Gray) thought ‘If it’s for the public good why can’t we do something? In a sense it was artists who found the site and came for it.”

Fairhurst added: “The whole history of the site was observation. It was observation of the stars, a very forward-looking discipline as is contemporary art. It’s just a different medium you’re looking at. We really needed to find a sustainable new use which would get the site up and running again. That helped in discussions with planning to find a new use for the site because it was in such a desperate way. Everyone wanted to find a use for the listed buildings that were up here.”

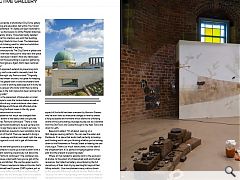

Centrepiece of the 21st century Calton Hill is The Hillside, an exhibition and office space embedded within the ground in front of the City Observatory. Fairhurst commented: “The Hillside Gallery, as the name suggests, is dug into the hill. As part of the historical research we identified that Playfair, when he built the original observatory, wanted it to sit on a perfect mount on a north/south/east west axis so this corner of the site had been infilled to get the landscape exactly as he wanted. Half the excavation was basalt and half was fill material which was a lot cheaper than excavating rock.”

The Hillside is joined by a refurbished City Dome gallery space and a learning and education hall within The Transit House. Fairhurst remarked: “It’s really just been restored to its original layout, we had access to all the Playfair drawings stored in the university library. Those held really detailed information on what his intention was with that building. That helped to bring it back to how it was. The telescopes are still in there and its being used for retail and exhibition space, it’s not been converted in any way.

“Collective Architecture did The City Dome in phase one of the project and that was really just to strip back the space to exhibit artwork because it doesn’t have any telescopes in it. The little Transit House building is used as a gathering space for small school groups. Again that’s been restored back to how it was.”

This light touch approach extends to preserving slots in the Observatory roof once used to manually track the telescope across the night sky. Fairhurst said: “Originally they would have had timber shutters, not great for keeping the rain out so we’ve glazed them in and the shutters have been reinstated. It is still a working telescope but will only be used by astronomy groups who know what they’re doing. The other telescope in the main space has been restored but it is not in working order.”

One omission is the placement of binoculars or small telescopes for people to scan the horizon below as well as above but even without any visual assistance clear views toward the Forth Bridge and Fife are still afforded while a restaurant boasting the finest views in the city gives Collective some welcome extra income.

To the casual observer not much has changed then but this belies the extent of the labour and cost poured in behind the scenes. Fairhurst continued: “There is road access but because the last building to be put up here was the dome 120 years ago there were no modern services. To open a commercial kitchen required a new substation to be dug into the bottom of the hill. Then we needed to bring a gas supply up the roadway and that was basalt right the way up. It was a challenge and a cost risk to get all these new services in.”

Throughout the site level ground is at a premium, prompting the architects to build up as well as down with a cantilever restaurant reaching precariously out above the cityscape below. Fairhurst continued: “The cantilever was very practical because underneath here you’ve got all the toilets, plant space and kitchen. We use the upper level to take in the views. There is nowhere to hide on this site, that’s why there’s a combined heat & power (CHP) system just so we didn’t have to use a boiler and a flue on each building.”

Key to the project was the landscape work to the spaces between each pavilion, which now double as an outdoor sculpture park and outdoor gallery in its own right. This aspect of the build has been overseen by Harrison Stevens who’ve work hard to overcome changes in level to create a fully accessible environment which allows the unfolding drama of the surrounding cityscape to play out as a diorama from the Old Town and Castle through to the New Town and down to Leith.

Beaumont added: “It’s all about viewing on a 360-degree viewing platform. You can see the water and Pentlands. It’s a place that lends itself perfectly to looking and thinking and it sets you thinking whether you’re looking down to the Parliament or Princes Street or hearing the one o’clock gun. There is so much history here, it is the seat of the enlightenment. It’s a perfect bringing together of the past and the present to exploring ideas.”

Where art has tended to elevate work to the exclusion of all else, to the extent of whitewashed walls and hushed reverence, the Collective Gallery are embracing the full cacophony of their host city by reaching far beyond their hilltop redoubt. Like mountaineers many visitors drawn to this pinnacle of the city’s cultural are now likely to do so ‘because it’s there’ in a pilgrimage few would have made for the galleries previous home. In doing so they are as likely to be captivated by the views within as without.

|

|