V&A Dundee: Overarching Ambition

17 Oct 2018

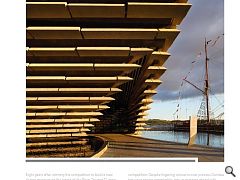

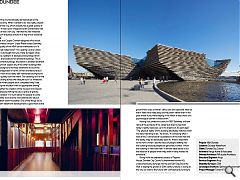

Dundee has long been severed from the river which gave it life but in turning back to the Tay it has rediscovered the timeless appeal of boundaries between land and water. this has not only altered the city’s geography but placed it firmly on the international map. Photography by Hufton + Crow.

Eight years after winning the competition to build a new design museum on the banks of the River Tay and 12 years after the first conversations surrounding a waterfront set-piece began Dundee’s V&A Museum has opened its doors to an expectant public, but is it £80m well spent? Urban Realm was among the first to step through the cliff-like concrete portal to find out.

Still defined by the 19th century jute trade Dundee took a symbolic step back towards its international roots in November 2010 when the Japanese architectural practice of Kengo Kuma & Associates was unanimously declared the winner of a design competition – amidst much angst at the time from the losing teams, who alleged unfairness in the competition. Despite lingering concerns over process Dundee has since shown remarkable unity in pressing ahead with an expensive public works programme at a time of national austerity, with ordinary Dundonians brought together in common purpose to reconnect the city with its lost waterfront for the first time in a generation.

Addressing journalists at the opening of the waterfront design centre Kuma was inevitably confronted by comparisons with Frank Gehry’s seminal Bilbao confection, with much speculation centring on whether Dundee’s newest edifice can replicate some of the Titanium-clad stardust of the Spanish Guggenheim: “Bilbao is a shiny monument, within the city”, Kuma responded. “With this building we draw people to the river and connect with nature.”

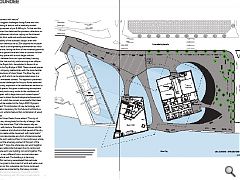

One of the biggest challenges facing Kuma was how to create a building of stature with a relatively modest floor space requirement of just 8,445sq/m. To that end the Japanese architect has balanced the priceless collections on a delicately cantilevered structure, relying on the inherent strength of 30m thick walls and reinforced steel beams to maintain stability of the acrobatic design, even with overhangs which extend as far as 20m beyond the museum footprint. The result is an engineering achievement as much as architectural one, taking the form of two inverted pyramids which separate at ground level and twist to connect to form high-level gallery space with a much larger volume.

The space between forms an open archway, framing views of both the river and city while serving as an oblique reference to The Royal Arch, demolished in favour of an access ramp to the Tay Bridge in 1966. These covered spaces form new and intriguing relationships with the more familiar Dundonian attractions of Union Street, The River Tay and RRS Discovery, all of which can be appreciated anew in a more intimate immediate context. This approach presented particular structural challenges for Arup as Kuma observed: “The tension is very important in the cantilevered sections to create covered spaces, this gives a welcoming atmosphere to the community and is very similar to the cantilevers of Japanese temples, with a large room and covered space.”

Kuma is keen to stress the technological achievements of this approach, which has proven so successful that ideas learned here will be applied to the Tokyo 2020 Olympics Stadium. He said: “A combination of new technology and natural materials is necessary for the future of architecture. Our new stadium will also feature that combination of wood and technology.

Speaking to Urban Realm Kuma added: “The city of Dundee has a very strong basis for the city of design. I like the texture of the stone here. That’s the reason why we used concrete with texture. We added small stones into the concrete that creates a kind of echo to that period of the city. We also tried to create subtle movement with metal joints.” The textured concrete doubles as a form of interconnected shell, uniting the roof, walls and floor in one continuous whole.

Asked about the emerging context of this part of the city Kuma added: “I hope the whole area can work together to achieve a new relationship between the city centre and the water. Maybe each new building can work together. The museum itself is very different from a normal rainscreen system and vertical wall. The building is in harmony with nature.” This harmony necessitated that particular consideration be given to the impact of wind and water, ever present dangers on this vulnerable site. Kuma continued: “Individual spaces are protected by the heavy concrete wall, we have limited small openings. The building itself is protected by the retaining wall. We tried to create natural flow and the whole shape of the building is against the wind.”

At the heart of the museum sits a recreation of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Oak Room, rescued from obscurity in storage to serve as a reminder of early cultural exchanges between Britain and Japan. Commenting on the interior approach Kuma said: “For the interior we tried to bring warmth and softness by using natural materials, the oak panels are not straight but instead have softness, randomness and rhythm. We thought that a museum in the 21st century should be a living room for the city. It’s not only for art lovers but for people to use as part of their daily life.”

The largest space is the dramatic main hall lined by hanging oak-veneered panels and dominated by a limestone staircase which still includes the visible fossils of sea creatures and plants which died millions of years ago. It is joined by a café, shop and visitor centre which go a long way to realising Kuma’s vision of a ‘living room’ for the city.

Kuma may have delivered V&A Dundee but the ultimate driving force behind the £1bn waterfront regeneration project has been Mike Galloway, executive director of city development with Dundee City Council. Asked about the transition from pipe dream to reality Galloway responded: “When Tayside House started to come down I think people in Dundee really believed we were serious about all the promises we’d made for the area. People felt it was a good time to happen, the right thing to happen but did they really believe it would get off the ground? Possibly not.

“I studied planning here in the 1970s and have worked throughout the UK in other post-industrial cities such as Glasgow, Manchester and London. When I came back here the journey of the city had already started based on the knowledge economy. What I wanted to do was really unleash the potential of the city, which actually has a great quality of life. Externally it had a poor image and even Dundonians had a poor image of their own city. I felt that the raw materials were here to turn the place around in a way which would be quite stunning.”

Gazing out at a Cooper Cromar-designed office block, butt of much media criticism, Urban Realm asked Galloway whether the quality of the V&A can be maintained or if it represents a high watermark? “I’m a planner and an urban designer and I was taught how you make European cities where you have a pattern of background buildings which create spaces and locations for landmark buildings. This is one of the landmark buildings, the station is another landmark building. I would not expect any of the other buildings that make up the background to these landmarks to be of the same style and approach in terms of their architecture but I would expect them to be really well mannered back=ground buildings with quality built into them. The cladding isn’t on the commercial building across the road yet but it’s a limestone building. I think when people see it completed they’ll see we’re providing the museum with an appropriate setting.”

Asked whether the creation of the museum and Slessor Gardens was already shifting the city’s centre of gravity Galloway responded: “It’s much easier for people to come down to the water now and the more attractions we put here to draw them down the better. One of the things we’re trying to do with waterfront developments is give them active ground floor uses so there’s cafes, bars and specialist retail so that it feels like a really easy journey down rather than in the past where if you were staying in the Hilton it was a heck of a psychological barrier to head down.”

Having first joined the council in 1997 Galloway will now retire at the pinnacle of his career but does he feel that today’s reality measures up to his dreams of 20 years ago? “The physical reality of this building absolutely matches what we were intending to do,” he avows. “It’s amazing when I look at the 3-dimensional visualisations of the main hall and the reality, they are absolutely spot on. What’s important to me now is when I see the faces of people walking into the building because people are genuinely wowed. I know the building so well now that I’m almost blasé about it but the reaction of people when they walk in really makes me emotional.”

Rising from the shattered carcass of Tayside House, Dundee City Council’s unlamented former HQ, unceremoniously dumped into the old Earl Grey Dock the V&A is slaying the ghosts of 20th century failure. In doing so the city can look to the future with confidence by turning to its own illustrious history in the deeper past.

|

|