The Macallan: Spirit of Innovation

17 Oct 2018

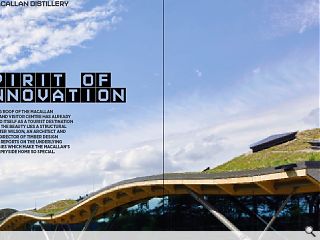

The rolling roof of the Macallan Distillery and Visitor Centre has already established itself as a tourist destination but behind the beauty lies a structural marvel. Peter Wilson, an architect and managing director of Timber Design Initiatives, reports on the underlying technologies which make the Macallan’s sweeping Speyside home so special..

Recent years have borne witness to a significant expansion in the Scotch Whisky industry: a global export success and a huge contributor to the country’s GDP, the bulk of the country’s distilleries are owned by a handful of international drinks conglomerates (e.g Diageo, Campari, Pernod), but there are still many successful ones that remain independent, such as Macallan, part of the Edrington Group and owned by the Robertson Trust. Outwith this core of existing producers, a plethora of new distillers have emerged over the past few years, some housed in previously mothballed premises bought out from larger operations within whose business plans these smaller facilities no longer have a role; some established in converted premises as ‘boutique’ distilleries; and a handful in entirely new buildings designed most often to be modern interpretations of the traditional appearance of a whisky-making enterprise. Few of these are large in scale and output, so when an existing and already large operation has the aspiration to produce substantially increased volumes of its internationally recognised spirit and decides to eschew the time-honoured look of a distillery in its new facilities, it’s perhaps time to review our preconceptions of how such an industry should, or could, represent itself to us and to the world.

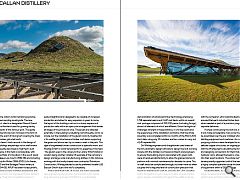

So, to the aforementioned Macallan and its new distillery and visitor centre located alongside its existing facility on the 390 acre (158 hectare) estate, Easter Elchies House near Craigellachie on Speyside. What makes the Macallan development different is both its sheer scale and a design that unquestionably departs from the conventional form and image of a traditional distillery. That, and the fact that the new facility has cost £140 million - part of a much larger overall investment of £500 million on the site by the Edrington Group - is not only a massive display of confidence in the future of the brand, but is also one of the biggest private sector investments in industrial property development seen in Scotland in recent years. This same confidence is immediately apparent in the choice (through competition) of Rogers, Stirk, Harbour and Partners as the architects for the new development, along with ARUP as the project’s engineers.

But first some background to the design. The Macallan single malt whisky was first produced in 1824, since when it has established itself as one of the most famous whiskies in the world and the reason Edrington wished to develop a contemporary distillery that would reveal the production processes and welcome visitors whilst remaining sensitive to the beauty of the surrounding countryside. The new development is, in fact, sited in a designated ‘Area of Grand Landscape Value’ amid farmland used for growing barley, one of the key ingredients of this famous spirit. The gently undulating surrounding hills are now mirrored in the form of the building, even to the point of having turf covering the linear sequence of its five, timber grid-shell roofs.

Whilst the design team’s track records in the design of engineered timber buildings are perhaps not so well-known as their other, more usually described as ‘high-tech’, built outputs, their experience in this field is considerable, with the architects’ own portfolio of innovation in the use of wood dating from the Bordeaux Law Courts (1992-98) and including The National Assembly for Wales (1998-2005) LAs Arenas, Barcelona (1999-2011) and the Bodegas Protos winery at Penafiel in Spain (2004-08). ARUP has been no less prolific, its latest groundbreaking success in timber engineering and the development of new forms of engineered timber detailed elsewhere in this issue. Their joint competition success in this instance cannot therefore be considered to be either accidental or inappropriate.

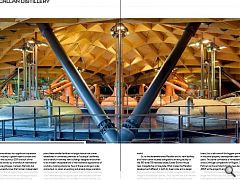

Diagrammatically, the internal planning of the distillery is quite straightforward: designed to be capable of increased production and allow for easy expansion in years to come, the layout of the building is set out in a linear sequence of production cells within an open-plan arrangement that reveals all stages of the process at once. These cells are reflected externally in the building’s undulating roof silhouette. So far, so simple, but the installation of the glulam and LVL facetted 3m x 3m waffle grid structure and timber roof decks supporting the green roof above was by no means a walk in the park. This type of engineered timber construction is specialist work, and Wiehag GmbH is world-renowned for its expertise in this field - the glulam used in the canopy to the Canary Wharf station in London being another notable UK example of the company’s design and large-scale manufacturing abilities. In this instance, working with the locally-based main contractor, Robertson Construction, Wiehag elected to use its preferred installer L&S Baucon GmbH due to the roof’s complexity.

Timber grid-shell roofs, of course, are not an especially new engineering phenomenon, but one that is 207 metres long and covering an area of 13,620 m2, is undoubtedly unusual and, with five undulating domed volumes and an external canopy, is not based upon simple, repetitive construction: this is an extraordinarily sophisticated demonstration of advanced timber technology employing 1,798 separate beams and 2,447 roof decks within an overall roof package comprised of 350,000 pieces (including fixings), almost all elements of which are different. Given the logistical challenges inherent in these statistics, it is to the credit (and the experience) of the installation contractor, that the whole assembly was completed within six months of the March 2016 start date, using only 20 installers and two cranes to carry out 4,245 separate lifts.

Six Wiehag engineers and draughtsmen used state-of-the-art parametric design software to design the roof, working closely with the distillery’s principal architects and engineers to ensure the building physics associated with green roofs were all resolved satisfactorily to allow the grassed domes to perform with minimal maintenance for decades to come. This in itself would be complicated enough, but even more so when coupled with a required level of construction precision that meant no tolerances to work to, since the 3m x 3m cassettes had to fit together in such a way as to allow an even shadow gap to appear consistently throughout the waffle structure. All of the timber elements were fabricated in Wiehag’s factory in Austria, using advanced CNC machines to meet the design team’s high quality and finish requirements. This, together with the company’s ultra-sophisticated barcode system, ensured that each individual timber item came to site exactly when needed as part of a precision programme involving 130 separate deliveries.

If simply constructing the roof was a complex exercise, it was made considerably more so by the fact that it had to be assembled over the pre-installed whisky stills and other distilling equipment and machines. As a result, innovative propping solutions were developed to work around the delicate copper structures, an ongoing process for Baucon, with the Wiehag team calculating the forces through the props and designing connections for them that, with the use of hydraulic rams, allowed the beams, once installed, to be lifted into their exact locations. The whole roof therefore required to be temporarily supported until all the beams were in position - a highly complex operation since the beams had to be capable of adjustment within a 150mm range.

Understandably, as a result of disasters such as at Grenfell Tower, increased attention has been placed upon the fire performance of timber construction, albeit that the material had no part in that tragedy. Nevertheless, the same level of care and concern given to the construction process was applied to site storage and fire prevention throughout the distillery’s roof assembly. First, a programme was devised to limit the amount of timber on site at any given time, thereby reducing the risk of fire and any other damage to the material itself, whilst the delivery programme was also coordinated to ensure site staff were ready to receive each of the aforementioned 130 deliveries and that space was available to offload and store the engineered timber components safely.

For many visitors to the completed building, much of this attention to detail will not be immediately apparent, nor the way the building sits so naturally within its landscape: all will seem as it should be, even to the way in which the lighting progressively alters along the length of the building interior to reflect the changing colour of the spirit as it matures. The overall impression however, is of a design that not only draws successfully upon its geographical and cultural context but which is also a superb demonstration of advanced timber engineering and engineered timber products. The processes undertaken in the design and construction of the new Macallan distillery also highlight the extent to which the properties and characteristics of engineered timber products and systems need to be fully understood to ensure the most appropriate technologies available are employed in the delivery of beautifully constructed buildings that are as safe during their assembly as they are intended to be throughout their life. The lessons to be gained about these products and systems by architects and engineers working in Scotland are huge.

|

|