Leicester: Middle Ground

16 Oct 2018

Best known for its cheese and Premier League winning football team Leicester is now building a reputation for architecture. As this modest midlands town emerges from the shadow of its larger neighbours urbanist John Lord undertakes a fact finding visit to see what lessons it offers to other struggling secondary cities.

Leicester is an unregarded sort of place. Pevsner warned that the city “may strike the visitor as drab”, while W G Hoskins’ 1970 Shell Guide said that it “is at first sight a totally uninteresting Midland city…a desert of hundreds of acres of little red-brick terrace houses”.

Hoskins quoted the writer and Leicester MP Harold Nicolson’s description of “that ugly and featureless city”, before grudgingly admitting that “Leicester, which makes so unfavourable a first impression, deserves a couple of days’ exploration on foot”. It certainly does and, if Leicester takes a while to reveal its best features, it proves to be an engaging place and something of a model for the revival of Britain’s struggling medium-sized cities.

It is also an extraordinarily interesting community, the only city of significant scale in Britain that does not have a majority ethnic group. In 2011 just 45% of residents described themselves as White British, down from 61% in 2001. 28% were of Indian ethnic origin, 5% were White Other, and 21% were of other ethnic origin. But rapidly increasing diversity does not mean that Leicester is becoming “less British”: researchers at CoDE in Manchester point out that growing numbers of people of non-White British origin identify themselves as British.

Leicester has been a popular destination for migrants since the 1950s, especially the Gujarati Indians who came from East Africa to work in the garment industry and light engineering firms like Imperial Typewriters. In 1972 the Ugandan dictator Idi Amin expelled his country’s Asians. About 5,000 came to Leicester, and they are now recognised as one of Britain’s most successful immigrant groups. English-speaking and enterprising, these “twice immigrants”, were confident and adaptable. They proved to be “adroit entrepreneurs, top of educational league tables, unstoppably aspirational”, according to Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, a member of that generation. And immigrants are still attracted to Leicester’s tolerant and welcoming environment: in 2011 more than a quarter of the city’s population was born outside the UK.

Diversity is not a guarantee of integration and ethnic Indians, for example, are still concentrated in neighbourhoods in the east of the city, but Census data show that BME residents of all origins are steadily dispersing to suburban locations and into the Leicestershire commuter belt. What is striking is how successfully Leicester has adapted to change and made a virtue of its diversity. According to the journalist Peter Popham, “Leicester has become the poster city for multicultural Britain, a place where the stunning number and size of the minorities…are seen not as a recipe for conflict or a millstone around the city’s neck, but a badge of honour”.

Leicester is not especially prosperous, but it is outperforming the other medium-sized cities visited for this series. IBM recently opened a service centre in the city, and the financial services business Mattioli Woods is moving hundreds of jobs from its edge-of-town base to the New Walk Centre. Leicester’s entrepreneurial spirit is reflected in a strong business start-up rate and a cohort of fast-growing businesses, the population is youthful, and the city’s continuing manufacturing tradition means that the value of goods exported easily exceeds service exports. It’s just over an hour by train to London, raising the possibility that this corner of the East Midlands will soon be subsumed into the Greater South East labour market. All this may explain why, albeit by a narrow margin, a majority in Leicester voted to remain in the EU, while Bradford, Coventry, Hull and Stoke all chose to leave, in some cases by an overwhelming margin. If the EU vote was, as Laurie Penny said, “a referendum on the modern world”, it’s not surprising that left-behind places used it to vent their anger and frustration. Leicester’s Yes vote, however slim, suggests that it is a happier and more confident city than many of its peers.

Back to the place itself. While too many developers and politicians (and others who should know better) live in a fantasy world of iconic buildings and transformational projects Leicester is a good example of the value of ordinary things done well. The quality of city life is not defined by the sugar-rush of icons and flashy gestures, but by the accumulation of small daily pleasures. Leicester offers many of these, and an energetic City Mayor has made placemaking one of his top priorities. It only really stumbles when it loses touch with its essential character and qualities.

We should start by acknowledging an epic blunder: the construction, in slow-motion phases, of the orbital road which encircles most of the city centre with a ring of fast-moving traffic. It’s disastrous, and the St Nicholas Circle/Southgates section is worst of all. Completed in 1967-68, it “shattered the medieval town plan completely” (Pevsner) and isolated the historic Castle-Newarke enclave from the city centre. The road goes a long way towards defining the visitor’s experience of Leicester: there’s what’s within the ring (mostly good), what’s beyond it (also mostly good) and the “uncongenial” experience (Pevsner again) of navigating between the two.

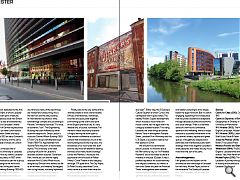

Jones the Planner, in their excellent essay on Leicester, describe the City Mayor’s plans to repair the damage done by the orbital road and some remedial measures have already been taken, notably at Magazine Square. But after 50 years the barrier created by the road has been embedded in Leicester’s urban fabric. FOA’s glamorous 2008 John Lewis store at Highcross is a case in point: it is, of course, infinitely more stylish than anything else in the neighbourhood but it’s a classic drive-in/drive-out retail destination, situated next to the orbital road and connected by an enclosed footbridge to a car park which is even bigger than the shop. The effects of that are very clear elsewhere in the city centre: the hermetically-sealed Highcross complex – John Lewis, the adjoining mall (currently being expanded), a cinema complex and a street of multiple restaurants – was teeming when I visited, but the rest of the retail zone is visibly struggling and the rambling Fenwick’s store in Market Street closed in 2017.

In recent years two unlikely events have raised Leicester’s proverbially low profile. In 2012, the mortal remains of King Richard III were unearthed in a council car park, cueing a tidal wave of hilarity on social media before the Council stepped in to claim the late monarch as one of their own. In 2015, after a solemn procession through the city, Richard’s bones were interred in Leicester Cathedral. A year later, Leicester City – under their charismatic manager Claudio Ranieri - won the Premier League title, an achievement that united the footballing world in surprise and delight. The “romance” of the Foxes’ unexpected success was mostly “mawkish guff”, according to Janan Ganesh. Rather, it was the result of the application of sports science and inspired talent scouting. The lessons, Ganesh says, go well beyond football. They apply equally “to modest cities adapting to globalisation and…individuals navigating an insecure world”.

The reinterment of a monarch of dubious reputation may seem like an unlikely catalyst for regeneration but Leicester has carried the whole thing off very successfully. The archaeological excavation, conducted by a team from Leicester University, generated a huge amount of interest and local pride. St Martin’s, a parish church elevated to cathedral status in 1927, was reordered to create the burial site where a fine tomb was installed. Two magnificent new stained glass windows were commissioned, designed by Thomas Denny. The redesigned Cathedral Gardens is a delightful and popular open space, while – just around the corner – Maber Architects’ Richard III Visitor Centre is a discreet intervention which tells the story of the king and the discovery of his remains, and preserves the original burial site. All this has given a boost to cafes and restaurants in the neighbouring Old Town area.

From the Cathedral it is a short walk to the splendid market, “like something you might find in Flanders”, according to Jones the Planner. This is the real thing: a noisy, busy, vital space under a utilitarian roof, which is due for a modest makeover in the coming year as part a project which will tidy up the whole area, but hopefully not too much. The market is overlooked by the jolly, Italianate Corn Exchange, with the smart but slightly underwhelming new Food Hall next door. A few yards away is Francis Hames’ Town Hall, which opened in 1876, described by the Leicester-based planner, Michael Taylor, as “calm and civilised…a large house rather than a civic building”.

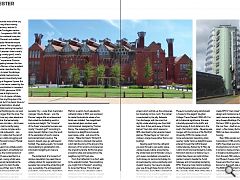

Heading west from the cathedral you pass through a new public space, Jubilee Square, before encountering the orbital road and St Nicholas Circle, a grim super-roundabout occupied by a multi-storey car park and a Holiday Inn, all overlooked by some wretchedly poor student housing. You have to navigate your way through these horrors to find the impressive Jewry Wall, a remnant of the Roman town, and the neighbouring St Nicholas Church. The Jewry Wall Museum (currently being refurbished) is housed in the elegant Vaughan College (Trevor Dannatt, 1960-62). For all its historical significance, this area is brutally exposed to the traffic and hard to enjoy. A short distance to the south, the historic Castle – Newarke area merges with the campus of De Montfort University (DMU) to create a much more secluded and rewarding urban quarter. Castle Yard is a delightful space, entered through the half-timbered Castle Gateway, flanked by St Mary de Castro church and overlooked by Castle Hall which stands on a shallow rise. In Castle View there is an idyllic kitchen garden, tucked in beside the Turret Gateway and immaculately tended by DMU. There are more historic buildings on the Newarke before we encounter the university estate. Most of the latter is of no great distinction, but Mill Lane has been upgraded and pedestrianised to create DMU’s “main street” and both the design and maintenance of the public realm here are outstandingly good. The zany Queens Buildings (Peake Short & Partners, 1993) is good fun and, facing the river Soar – itself an underutilised asset - a fine hosiery factory (dated 1925) has been converted into student housing.

New Walk was laid out by the Corporation in 1785, and has been a traffic-free street ever since. It has been knocked about a bit over the years, but it remains a lovely promenade, unique in England. Building plots were released from the early 19th century onwards, and Museum Square, De Montfort Square and the Oval were subsequently laid out on the south side of the street. The 1836 Nonconformist School was converted into the Museum & Art Gallery in 1849. Its hidden treasures (typical Leicester) include a small but high quality room dedicated to the Arts & Crafts movement, in which Leicester played a significant part; it features furniture designed by local man Ernest Gimson. There is also an extraordinary gallery devoted to Leicester’s world-class collection of German expressionist paintings. You can take a short detour here to visit Nelson Street and enjoy Percy Grundy’s 1932 art deco Goddard’s Silver Polish Co factory, and the same architect’s parade of shops on London Road.

New Walk is the best line of approach to the University of Leicester, a mile south of the city centre. Leicester gained university status in 1957, when Leslie Martin produced a plan for a group of science buildings at the north end of the site. James Stirling and James Gowan’s Engineering Building (1959-63) “broke violently away” from Martin’s formal, well-mannered ensemble. In a city where so many of the best things are modest and unassuming, this is the star turn and the only building of international importance: wilful, bewilderingly complex and, according to Pevsner, “inimitably individual”. For once, an authentic “icon”. The Engineering Building was soon followed by other assertive neighbours: Denys Lasdun’s muscular Charles Wilson Building (1962-67) and Ove Arup’s tall Attenborough Tower (1968-70). Approached from Victoria Park, they form a memorable skyline. The University is the ideal jumping-off point for Leicester’s arcadian southern suburbs: Clarendon Park, where you can see the highly desirable Arts & Crafts White House, designed by Gimson who started out life as an architect, and wealthy Stoneygate, with its big houses, including Inglewood (also by Gimson), university halls of residence and botanical gardens.

Finally, back to the city centre and its intimate streets of brick and terracotta. Offices, small factories, workshops, churches and pubs jostle together, summoning up the charm and spirit of the English provincial city. It’s very likeable and, of course, vulnerable. The market in these secondary locations is fragile, leaving the door open to “the boorish indifference to scale and context that characterises much of the new building around the ring road…the shoddiness of so much post-war stuff and the silly show-off attention-seeking shininess of so many recent buildings” (Jones the Planner). I would put the oppressive form and bulk of Rafael Viñoly’s Curve Theatre in this category, although JTP quite like it. The City Mayor, Sir Peter Soulsby, described Curve, which came in at more than twice the original budget, as “the most expensive and disastrous project this city has ever seen”. Either way, the St George’s Cultural Quarter of which Curve is the centrepiece hasn’t quite clicked. The nearby Phoenix Square development, which includes a much-loved art house cinema, has not aged well in its unhappily isolated location. This being Leicester, the small things are better: Makers’ Yard in atmospheric Rutland Street, Leicester Print Workshop and the LCB Depot, a successful creative hub that opened in 2004.

We shouldn’t be sentimental about Leicester. As Hoskins said of the 19th century city, it is “no Paradise Restored” and it has made its share of mistakes in the past 50 years. It has a justified reputation for social harmony and religious tolerance, but there is a dark side. Earlier this year the Financial Times’ investigations team revealed abuses and exploitation in Leicester’s garment industry, with factory owners and retailers colluding to drive wages below the legal minimum. But it is still an engaging, appealing and civilised place that has proved resilient and adaptable through decades of profound economic and social change. There is a manifest sense of a new-found confidence, optimism and wellbeing, thanks in large measure to sustained investment in the city centre’s streets, squares and green spaces: a thoughtfully designed and admirably well maintained public realm strategy which knits together Leicester’s small pleasures and makes the city much more than the sum of its parts.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to two experts on the architecture and townscape of Leicester for their help. Michael Taylor, author of the invaluable The Quality of Leicester and Chris Matthews, half of Jones the Planner.

Sources

Centre for Cities (2012), Cities Outlook 1901

Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (nd), Geographies of Diversity in Leicester, University of Manchester

W G Hoskins (1955), The Making of the English Landscape, Hodder & Stoughton

W G Hoskins (1970), Leicestershire: A Shell Guide, Faber & Faber

Jones the Planner (2014), Towns in Britain, Five Leaves Press

Nikolaus Pevsner and Elizabeth Williamson (1984), The Buildings of England: Leicestershire and Rutland, 2nd edition, Yale, New Haven and London

Michael Taylor (2016), The Quality of Leicester: A journey through 2000 years of history and architecture, 3rd edition, Leicester City Council

|

|