Smart Cities: Binary Choices

27 Jul 2018

As developments such as Masdar City and Songdo reshape what our urban environments can be we take a look at Bristol and Glasgow to see how these ideas can be put into practice in the more chaotic reality of our existing ‘dumb’ built fabric.

In cities around the world the echoing sound of jack hammers and drills is being joined by the clacking of keyboards and the hum of computers tasked with building a new generation of cities based on silicon as much as bricks and mortar. A new breed of brash and flash ‘utopias’ from Masdar to Songdo is emerging across the Far and Middle East fueled by petro-dollars and double-digit growth rates. The more prosaic retrofitting of sensors and fibre broadband in places such as Bristol or Glasgow offers a similarly illuminating view of our future if less immediately apparent. Can these sci-fi visions deliver their promise of clockwork cities where public services such as transport, sanitation and health work harmoniously together for the benefit of all?

Encompassing all of these developments is the nebulous concept of smart cities, a catch-all term describing any digital involvement in our analogue world which promises to reshape our relationship with the environments we inhabit. In an effort to wrap our heads around the opportunities and threats such technology represents Urban Realm caught up with Tony Mulhall, associate director land professional group at the Royal Institution for Chartered Surveyors for his insight: “We want to make people aware of the link between the components underpinning big data and the better use of property assets and infrastructure from a management, construction and investment point of view.

“Purpose built cities are an interesting phenomenon because cities haven’t typically arrived in that form. I know we’ve built New Towns but this type of new city, highly enabled technologically, is different. It’s very interesting to look at plans of Masdar carefully arranged on a square grid but beyond the square nothing happens. The smart city as an individual construct is only responding to a minority need.”

With the populations of the world’s largest cities exploding, the World Economic Forum calculates that Delhi in India will vie with Tokyo to be the most populous city in the world by 2030, pressures are building on authorities to ensure that infrastructure development can keep pace. Mulhall added: “The challenge is more about how you get the benefits of smart city technologies in very impoverished places. You have huge populations turning up at cities all over the world without any plan.”

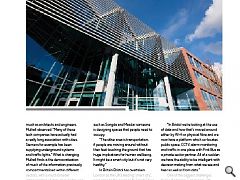

In order to rise to these challenges organisations such as RICS are increasingly finding themselves in the company of technology giants such as IBM and Accenture, as much as architects and engineers. Mulhall observed: “Many of these tech companies have actually had a really long association with cities. Siemens for example has been supplying underground systems and traffic lights.” What is changing Mulhall finds is the democratization of much of the information previously compartmentalised within different sectors, with a much broader categorization of data, knowledge and understanding now possible.

Mulhall continued: “The architectural community are at a critical point in the sense that we now have all this data but just because we have the opportunity doesn’t mean we find better solutions. We had a lot of data in the sixties about how to build fantastic cities and we ended up making a leap from that analytical information to solutions without a proper insight into what people really need. At the bottom of architectural propositions such as Songdo and Masdar someone is designing spaces that people need to occupy. “The other area is transportation, if people are moving around without their feet touching the ground that has huge implications for human wellbeing. It might be a smart city but it’s not very healthy.”

In Britain Bristol has overtaken London as the UK’s leading ‘smart city’, according to the second UK Smart Cities Index, in large part owing to the creation of an operations centre which unifies emergency services and boasts a traffic management system in control of over 200 sets of traffic lights. Its operations head, Pete Anderson, said: “There are five pillars of a smart city in the form of energy, public space, transportation, water and health. That is born out of what we can do with data and how that can be used to inform the flow of traffic or more efficient use of energy and distribution.

“In Bristol we’re looking at the use of data and how that’s moved around either by Wi-fi or physical fibre and we now have a platform which co-locates public space, CCTV, alarm monitoring and traffic in one place with First Bus as a private sector partner. All of a sudden we have the ability to be intelligent with decision making from what we see and hear as well as from data.”

One of the biggest challenges facing Anderson is engaging with people and communicating real world improvements without bamboozling them with technobabble. “One example is tele-care which enables somebody to live independently with alarms and panic buttons,” says Anderson. “The principle is being able to introduce a relatively basic bit of technology into someone’s home to give them independence but also the ability to speak to someone for reassurance.”

Of course, with this wealth of data comes great responsibilities, how do we manage the conflicting priorities of the power of data and individual liberties? “Due diligence is huge and that’s one of the biggest parts of engagement”, explains Anderson: “We need to be very upfront about the level of data we hold and how long we retain it.”

Further north Glasgow has made rapid progress in the digitization of services but how far along the road to becoming a Smart City is it? Since being selected as a UK Future City demonstrator Glasgow has gone on to become one of three ‘lighthouse’ cities (alongside Rotterdam and Umea) to strike out and accelerate progress towards a low carbon, efficient and resilient future. Gary Walker, divisional manager for scientific and regulatory services at Glasgow City Council, said: “There is so much you can do in that space, whether it’s the Internet of Things, data or an operations centre, making your staff more mobile or interacting with citizens. Glasgow can do so much more but we’ve achieved a significant amount.

“We’re looking to make our staff more mobile so rather than go back to the office and fill out paperwork and systems they can actually do it out in the field. Our environmental health officers for example will be able to carry out food inspections on a mobile, complete the paperwork online and give an electronic copy of that to the business.”

What sort of buy-in are you getting from the public? Is there any skepticism that this is being driven by cost cutting and not improving services? “We’re open and honest about what we’re trying to achieve. The MyGlasgow app was really well received and has 20,000 plus subscribers because people do want to interact with the council in a different way, they’re quite happy to use a mobile phone rather than wait on a phone operative.”

Partnerships with the private sector and academia are also key, with GCC keen to bring on board expertise wherever it may be found. Walker said: “We have worked with the academic sector, big businesses such as Siemens, Scottish Power, Microsoft and also SME’s. In conjunction with the City Deal the Tontine building was created as a Google office type environment to bring SME’s together and work for the city to present challenges to work on together. The council doesn’t need to deliver everything itself.”

Sighthill is shaping up as a possible flagship component of Glasgow’s smart city ambitions with a unique opportunity to establish a new district from scratch. Mindful of this the latest breed of smart traffic lights are proposed as well as intelligent street lighting and electric vehicle charging.

Mindful of the exponential rise in data and the challenge of making sense of it all Walker acknowledged: “As a council we didn’t necessarily have that skillset. We had lots of people who worked with data on spreadsheets but it’s about operating at scale. To that end the council has built Trafcom, a centralized CCTV control room, which monitors everything from crime to traffic lights, the most recent of which are connected to embedded loops in the road capable of monitoring how many cars travel over. Unifying all this new kit is an exponential increase in data, prompting the formation of a new cloud-based application, The City Data Hub, which facilitates easier and wider access to the reams of information produced. “Once we created the City Data Hub we could store the data and use it for other purposes,” notes Walker. “That was generating megabytes per minute. This is a relatively new area for us but we have support from a small data team as well as data scientists from Strathclyde and Glasgow universities.”

Fundamentally nature is chaotic, people even more so, even when armed with the perfect data set you have to stress the limit of what can be achieved. No matter how many signaling improvements we make congestion will return if the road isn’t wide enough to accommodate the volume of traffic. We can still learn much from our analogue ancestors (such as the Victorian engineers who designed London’s sewerage system) when we are designing the cities of tomorrow and this is perhaps the smartest approach of all.

|

|