Learning Experience: Flash of Inspiration

27 Jul 2018

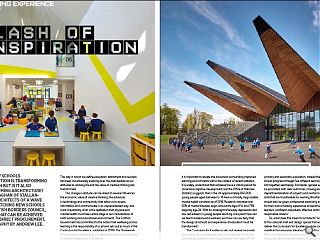

A wave of schools construction is transforming education but is it also transforming architecture? Keri Monaghan of Stallan-Brand, architects of a wave of eye-catching new schools for Scottish Borders Council, shows what can be achieved through direct procurement. Photography by Andrew Lee.

The way in which we define education, attainment and success has been incrementally evolving over the past decade as our attitudes to working life and the value of creative thinking has transformed.

This change in attitude can be linked to several influences; the economic value of creative thinking; the advances in technology and connectivity that allow us to access information and communicate in an unprecedented way; and most importantly of all, is the realisation that physical and mental health must take centre stage in our consideration of both working and educational environments. The Scottish Government has committed to the notion that wellbeing across learning is the responsibility of us all and sets out as much in the Curriculum for Excellence, published in 2008. The ’framework for learning and teaching’ as it is described, sets out a manifesto to transform education in Scotland.

Taking a moment to elaborate on the well-being agenda, it is important to situate the discussion surrounding improved learning environments within the context of recent statistics. It is widely understood that adolescence is a critical period for social and cognitive development, but the Office of National Statistics suggests that in the UK approximately 850,000 young people aged between 5- 16 have a clinically diagnosable mental health condition as of 2016. Research indicates that 50% of mental illnesses begin around the age of 14, and 75% begin by age 24. With an onslaught of anxiety, depression and low self-esteem in young people reaching crisis point how can we teach resilience and wellness; and how can we deny that the design of schools and experience of education must be transformed?

The Curriculum for Excellence sets out several proposals that should be considered as part of the solution. Firstly, the experience of learning should be coherent from ages of 3-18 rather than fractured between year groups and split into primary and secondary education, instead the learner journey should progress through five different learning stages that knit together seamlessly. A broader, general education should be promoted with clear outcomes, moving away from the departmentalisation of subjects and reinforcing life learning skills that are transferable for working life after school. Students should also be given professional autonomy and responsibility for their own schooling experience to become ‘…successful learners, confident individuals, effective contributors and responsible citizens.’

So, what does this mean for architects? How to we respond to this colossal brief and design spaces that equip schools to deliver the Curriculum for Excellence – how can we physically manifest this emerging ideology? The truth is, we don’t know. We’re in unchartered territory for educational design; it’s no longer just about creating a series of spaces to socialise, gather, enjoy quiet time etc. it’s about redefining everything we imagine about what makes a school a school: where it is situated, who it belongs to, how it looks, how spaces are arranged, what defines a classroom. What we can be certain about, however, is that the institutional school typology, with the standard corridor and classroom arrangement, is obsolete. Our idea of school should become less of a compartmentalised building and more a series of events, playful and diverse to suit a variety of needs and learning activities as education starts to be delivered in a less prescriptive way.

What’s more, to successfully reimagine learning environments, designers must resist the temptation to act as solo agents and genuinely collaborate with Directors of Education, Local Authorities, teaching staff and students to change the culture around education. After all, the Curriculum for Excellence asserts that ‘wellbeing is the responsibility of us all’.

Putting form to theory, the reimagining of learning environments comes in two parts; repurposing or refurbishing the existing school estate to enable buildings to facilitate the Curriculum; and building new premises that are tailored to suit. In our studios, we are currently developing our interpretation of how the new school might tackle the brief, which has been developed in close conjunction with teachers, innovators in education and the ambitious Scottish Borders Council.

The Jedburgh Intergenerational Learning Campus is ‘a school without walls’, unique in its spatial arrangement, and open to lifelong learners and the community. Part of the driving force behind the design of the school is that the students take ownership over their teaching space. Where, in a typical high school, students are dislodged between lessons hourly, and traipse between a series of uniform classrooms to any of the sixteen subjects they must attend in first and second year; the Jedburgh Learning Campus proposes that we abolish the classroom entirely. Rather than provide small, enclosed rooms that are in the domain of the teaching staff for an individual subject, classes will be delivered in larger cluster zones where students occupy the same space throughout the day and teachers travel between different cluster zones to deliver lessons. These larger, more flexible teaching spaces allow a variety of classes to take place in one space which promotes the overlapping of subjects and ideas, allowing more creative methods of teaching and learning to evolve.

This will fundamentally change the relationship young people have with their school environment and encourage a progressive pedagogy where cross-curricular, thematic learning takes favour over a formulaic, exam-focussed education. Critically, the alternative layout will provide young people with the mechanism to take ownership over their own environment, become more confident and self- directed, learn more creatively by connecting different subjects and understand the relevance and outcomes of their learning.

Within these cluster zones, there must be a well-defined structure to the space that can accommodate places for gathering, presentation, listening, reading, socialising, retreating, cooking, making and study but all of these are interlinked in the one space. Designing a truly flexible space, poses challenging architectural problems to which a variety of solutions could result in schools with more character and identity that makes for a richer schooling experience. Defining clearer breakout areas, creating themed learning environments, and investing in the correct furniture and fixtures to allow these activities to work in conjunction, is key to the success of the scheme.

We have been lucky to build a relationship with a confident and imaginative client and robust briefing and consultation has made this experimental school model possible, but it is by no means a new idea. De Nieuwste School in Tilburg, established in 2005, operates differently from many other schools in the Netherlands by encouraging students to carry out their own research throughout the school year and consult with learning coaches for guidance when required – the principle is that students store information better when they construct it themselves. Further similarities can be found in their promotion of ‘interdisciplinary cross-links’ where Humanities, Sciences and Arts are combined where possible. Looking to our neighbours for inspiration, the Finnish New Nordic School in Espoo also promotes personalised learning whilst prioritising creativity, innovative thinking and mindfulness.

Beyond the idea of redefining the internal arrangements of schools and interrogating how information is delivered, we must also consider where new schools are situated and who they belong to. Again, the Scottish Borders Council are being transformative in their thinking with regards to how the school can be of benefit to the public and reinforce the already established networks and communities that keep towns in the Borders functioning. As such, the Jedburgh Intergenerational Campus has been situated close to the original high street to become intertwined into the town’s historic centre. The structure is open and serves the citizens in a way that closed, institutional school buildings have failed to do so previously. As well as incorporating early years, primary and secondary students, there will also be provision for further education and community enterprise. Workshop spaces, studios, allotments and leisure facilities all feature in the learning quarter which will become a place of event and social cohesion.

The community not only benefits from the vast number of facilities, shared resources, experience, skills and opportunities; but everyone serves to benefit from an inter- generational transmission of knowledge. Creating more innovative and inclusive teaching environments will not only benefit young people in the immediate term but, in a wider societal context, will transform communities. In Scotland, there exists a latent potential for urban regeneration agencies to incorporate new life long education models into community initiatives. Closer working between the regeneration and education sectors would deliver more radical reform of our communities; especially in areas of deprivation. It is short sighted for regeneration agencies to leave education to education (and vice versa), we must promote collaboration and appreciate the greater value a new school or college can bring to a community beyond helping to sell houses. A greater understanding of the deeper learning ‘eco-system’ is required to ensure exciting new learning environments are more physically and culturally integrated into communities. If regeneration efforts are out of sync with local education, as is often the case, then development can become self-defeating.

In our view, it is not enough to focus on the refurbishment or delivery of a new school, or the rationalisation of a college estate to support learning as an isolated event. Rather it is the actual physicality, accessibility and attractiveness of the community context and its very direct integration with appealing and dynamic new learning environments that will deliver more prosperous and exciting places. Throughout this process, we have engaged communities and young people by asking them to consider the benefits of an alternative educational model that serves the community and what form it may take, with the hope that ultimately, we can begin to nurture more enterprising and confident communities.

Ours is but one interpretation of how transformational learning environments might be delivered, but schools will undoubtedly continue to change and may become even more amorphous as society advances digitally. What is clear, however, is that engaging young people in the design and format of their educational experience can provide learning at both an individual and societal level; as personal growth is coupled with socio-political transformation.

To return to the Curriculum for Excellence; the manifesto professes that the principles for curriculum design should be: challenge and enjoyment, breadth, progression, depth, personalisation and choice, coherence and relevance. The ideas are simple and should be obvious, but progress has been slow, the Curriculum for Excellence was published a decade ago and only now are councils and designers paying serious attention to the implications of this programme on the built environment.

What is fundamental to pull these ideas together is a set of principles to structure the design of an educational space or a philosophy for learning environments, and in whichever scenario, the focus on well-being for individuals and communities should be at the very heart of it.

|

|