PRS: Rental Potential

17 Apr 2018

While England has been quick to embrace the build to rent phenomenon Scotland has been slow to follow suit. A flurry of recent planning applications look set to change all that however, forcing the profession to wrestle with the issues presented for the first time. Here Paul Stallan details his own work off Glasgow’s High Street, discusses the wider implications such schemes present and irons out a few misconceptions about what the prvate rented sector is (and isn’t) along the way.

The homeless charity Shelter notes that; “as a result of a combination of factors, including the change in building patterns, a renewed emphasis from successive governments to owner occupation as the ‘desired’ tenure, and the implementation of right-to-buy, the mix of tenure has changed dramatically with much less social housing and much more owner occupation. The private rented sector has also seen growth as it fills the gap for households who have been priced out of owner-occupation, or who choose not to buy, but for whom social rented housing is also not a feasible option because of the demand on reducing stock. More people now rent in the private rented sector than they do from the council – a dramatic shift given that in 1984 almost half (49%) of all dwellings were council-owned.”

Against this context and stimulated by the monetary chasm that was the recession and the huge shortfall in housing provision nationally Government has lobbied the pension funds and financial community to consider a whole new residential property asset class; the funds investing in property typically preferring to place their monies into office, retail, leisure and even industrial before considering housing.

Until recent times institutional money had no residential product of a scale in Britain to interest them unlike in say Canada or the U.S. or closer to home Germany where over 60% of dwellings are rentals compared to the UK which has 17% of the population renting from a private landlord. A lack ofenthusiasm in recent times for renting in the UK is perhaps no surprise given the poor image the private landlord has enjoyed in this country as unscrupulous, owners who exploit tenants through rent rises, repairs and burgeoning deposits.

Backed by big money it is clear that the rental sector is currently undergoing a fundamental identity makeover one that is promoting a more responsible and affordable offer, an offer fuelled by rising house prices and limited access to borrowing especially amongst young people who now consider renting as a lifestyle choice. Cultural views on home ownership held by young people are very different from our parents and grandparents where renting was stigmatised with being working class and living in a ‘council house’. How things have changed.

The ‘Build to Rent’ sector is predicted to be huge and drive transformational change in housing provision. The market is well established in population centres in the South East of England, Manchester, Liverpool, however it’s worth recording that investment in the Scottish rental housing market has been impacted by the Independence votes and undoubtedly Brexit politics. Regionally there has been a definite drag in Scotland’s engagement with BTR. Off the naughty step for now ...

Scotland however is returning to its more boring and stable self meaning it is more capable of generating respectable yields for the Texas University Pension Fund or equivalent! BTR (or B2R it’s trendy acronym) in Scotland is misunderstood with many people thinking it is a form of glorified student residential accommodation. This perspective whilst unfortunate is changing. It is worth stressing that at the centre of the BTR business model is the need for housing to be fundamentally affordable to the widest cross section of the population. There is a view that new rental property is only catering for the millennial’s, this is not the case. Quality rental housing with good amenity is increasingly attractive to an older population and the senior living cohort especially. Build to rent development critically needs to be inter-generational in its appeal and attract different clients at different price points if its to deliver its objective of being super-scaled, managed, urban and residential led.

To hold and sustain a major BTR development demands major financial resources. For small to medium scale developers BTR is unattractive given that significant capital monies are required to deliver a complete environment without the prospect of incremental sales income. The interest charges on borrowings alone to complete a major project are enormous. The nature of who can afford to fund this type of initiative limits the range of players compared to more traditional residential development although there are some mainstream developers now effectively delivering turnkey projects, passing them onto the larger property funds when complete.

Beyond the big politics of Scottish Independence is worth noting that BTR development has also faced specific regional Town Planning challenges. One key obstacle is a tendency to over provide apartments with a single aspect. In the major centres in the South especially in London residential development densities and pressure on land are significant. These pressures drive more corridor style apartment residential typologies and encourage high rise solutions. Many English local authorities having had more exposure to the sector and have developed specific planning policies that identify BTR as different from mainstream residential accommodation. Scotland however, has no national policy view that differentiates ren tal housing from private for sale.

Build to rent projects that we are currently working on in Scotland are therefore designed with traditional residential policies and conform to the same criteria with regards to amenity, parking provision, environmental standards etc. There has been a definite challenge proving to our London clients that they are not disadvantaged; i.e. that we can still deliver a high quality product that is robust and affordable for lack of national BTR policy. For some funders this has again been another political disincentive and put Scotland in the ‘to difficult box’.

Scottish Government has also in very recent times promoted new legislation that advocated a form of ‘state’ rent control to combat and control exploitative landlords from overcharging on rental housing.

The legislation is good but at the time it was not clearly framed with regards to who it was aimed at.

For institutional monies it was again a red flag (much like the planning policy vacuum) and an added threat to the stability of their long term income. The reality is rather different as the legislation was aimed at making smaller rogue landlords more responsible and accountable.

Thankfully Government is catching up with BTR market needs and in attempt to provide sector confidence it has launched a ‘Rental Guarantee Scheme’. This scheme is essentially a Scottish Government bond that insures that if income falls below a certain level on a development then the public sector will step in to make up the shortfall. So to re-frame ... Scottish Government has tried to put checks and balances in place where if excessive rents are charged you get penalised versus if rent falls below a certain level there is assistance ...phew!

Why is any of this background on the financial dynamics of BTR important to architects? It is my view that to understand the architectural and place making opportunities that BTR presents we have to first understand how it is funded and what investor objectives are.

In summary ‘Build to Rent’ is both a volume and long term exercise for financiers. For build to rent to be attractive the offer has to be scalable because the revenue and yields are low. Money is not made quickly from BTR but is on a drip as part of a circa 30 plus year investment. To be attractive to renters the product has to be of a high quality and must be built to last. BTR is therefore focused on both quality of build and low energy for the simple reason that the financier retains the investment and is willing to spend more to pay less over the longer term. Architecture is therefore a definite consideration different from the more cynical house builder approach.

With huge financial outlay, long term payback and a requirement to deliver a high quality architectural environments there is pressures to drive economies in the forms of construction. Currently there are plethora of alternate structural and constructional systems being explored that are attempting to address this market. There is technology transfer from the hotel sector and from the advances being made in off-site manufacturing to address improved construction programming and minimise defects.

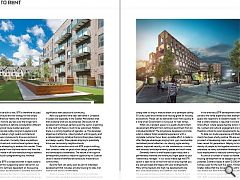

So given how BTR is funded and that it needs scale to succeed what can this burgeoning sector deliver for our cities. With build to rent less dependent on house price fluctuation and sales, development is generally procured in larger phases, consequently there is more opportunity to deliver local infrastructure, innovative district wide energy solutions, more sustainable architecture and of great significance new places and community.

New city quarters have been delivered in Liverpool, in Leeds and especially in the Greater Manchester area that evidence what can be achieved. Obviously not all development has been perfect given the sector is learning on the hoof but there is much to be welcomed. Notably there is a coming together of agendas; i.e. The developer objective of attractive, robust product with longevity and a national planning initiative that prioritises place making and design quality. Wow planets aligning to potentially drive new community neighbourhoods.

To build connections and root BTR projects withing their contexts relies on good urban design, placemaking and townscape consideration. The nature of this type of development presents a massive opportunity for Scottish cities to tackle brownfield land and build mixed tenure communities.

Build to Rent can easily exist as part of a blended development that includes, private housing for sale, mid market rent and social affordable.

What is unique is BTR’s ability to bring a muscular scale of urban residential development to a location much more quickly. So many of our urban regeneration projects simply take so long to mature reliant on a developer selling 50 units a year and limited local housing grant for housing associations. Places can be delivered much more quickly at a time when Government is crying out for new homes.

What can a resident expect in a quality Build to Rent development different from renting an apartment from an individual landlord? The progressive developers promote what is called a ‘hotel residential experience’ with a complete customer focus. Every possible effort is made to offer lifestyle advantages ranging from; gym membership, centralised parcel collection, car sharing, agile working spaces, improved security, on-site maintenance, common roof terraces, landscape amenity spaces and much more.

Generally there is a well located super lobby that is permanently manned and where you might speak to your ‘relationship manager’. In our social media age the BTR sector is keen to be on the front foot in ensuring that you are well provided and happy with your arrangements. Many of the medium and high rise developments are also encouraging active ground floor uses, avoiding the branded retailers and restaurants in favour of more independent businesses that help provide local identity and character.

In the ambitious BTR development there is a curated sense to the rental experience that attempts to second guess and respond to a residents needs. I would suggest that a careful balance is required to avoid a ‘Truman Show effect’ where people feel like actors in their own life. Context and cultural engagement at a local level is therefore critical to avoid developments being islands.

To date our studio experience with Build to Rent clients has been wholly positive. We are excited by the prospect of developing major urban gaps sites that have been vacant for generations. Helping to bring a greater density of people to live together around our city centres addresses so many sustainable headings from increased local employment to reduced commuting times.

As one of a number of routes to market for urban housing development to be stepped up it has great potential. Scotland needs at least 12,000 affordable homes a year for the next five years. Homeless charity Shelter states that the ‘Governments call to build 12,000 new homes per annum for the next five years is not being achieved, current programmes, at best, provide only half of that’. B2R is recognised as having a critical role in assisting local authorities address this shortfall. Watch this space ...

|

|

Read next: Maasai Centre: Glass Warrior

Read previous: Brodick Terminal: pushing the Boat Out

Back to April 2018

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.