Russian Revolution: Demolition of Paradise

17 Apr 2018

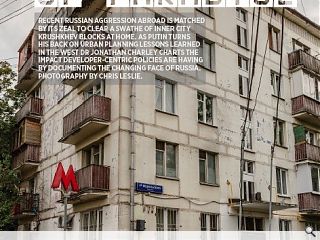

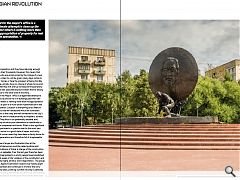

Recent Russian aggression abroad is matched by its zeal to clear a swathe of inner city Krushkhev blocks at home. As Putin turns his back on urban planning lessons learned in the west Dr Jonathan Charley charts the impact developer-centric policies are having by documenting the changing face of Russia. Photography by Chris Leslie.

In September 2017 Chris Leslie, award winning documentary photographer and film maker and Jonathan Charley, writer and teacher, went to Moscow for the Guardian to interview residents in the frontline of one of the biggest reconstruction programmes of modern times, the demolition of over four thousand apartment blocks that will affect the lives of nearly two million people. This essay looks at the historical context of what has become a highly controversial policy.Shortly after the death of Stalin, in the first few months of 1955, a strange new discourse appeared in the pages of the Soviet architectural journal Arkhitektura CCCP. For twenty years its editorials had proselytized a triumphalist language of monumental neo-classicism. Moscow had been rebuilt as the embodiment of an absolutist state, its radial plan reinforced by gigantic boulevards, the skyline transformed by seven kitsch wedding cakes, and its underground excavated and transformed into a palace.

Overnight the language changed. Doric columns and delicate mosaics were never going to solve the problems of post-war reconstruction and in particular the pressing need for new housing. There was only one solution; the prefabrication of buildings and the mechanisation of construction. The future was concrete. Architects, technologists and planners were challenged with solving the housing crisis within the space of twelve years. Concrete factories were built, construction workers retrained, and by the end of the decade the first experimental housing estate appeared in Novi Cheremushki in the south of the city.

A mixture of four storey brick built, and five and eight storey concrete panel housing, the neighbourhood was planned as an ecologically and socially integrated scheme complete with parks, pedestrian networks, schools, cinema, and shops. It was a remarkable achievement and an urban model that attracted the attention of architects from all over Europe who flocked to see the brave new world being craned into existence. Nobody then could have envisaged the consequences of this experiment. The five storey concrete panel block, popularly referred to as a Khrushchevka, named after the then Soviet leader, was declared the victor and within ten years virtually every town from Minsk to Vladivostok had its own Cheremushki comprised of these modest factory produced apartments. It was the prototype of a reborn Soviet modernity and such was its fame that non other than Dmitri Shostakovich penned an operetta that included the immortal words Cheremushki, Cheremushki… In every room, on every floor Municipal happiness! A Heavenly place without a trace, Of a dark and gory past...Paradise at last.

It is these flats that are in the front line of the demolition programme. The Mayor Sobyanin, keen to portray himself as the saviour of Moscow in the run up to the municipal elections this year has declared them obsolete. They ‘disfigure’ the city, are an eyesore, dilapidated and beyond redemption, it is time for them to go. In truth the discussion about what to do with the Khrushchevki has been going on since the 1980s. Nobody doubts that they need repair. There are problems with the roofs, the plumbing and sanitation needs upgrading, and they have no lifts. Cheaper then to raze them to the ground and decant the population to shiny new high rises that the Mayor’s office promise will be built in the same vicinity.

However, opponents of the demolition programme have argued, in a manner redolent of the debates back in the 1970s over the demolition of tenements in Glasgow, that with intelligent design the five story blocks can be remodeled and most importantly therefore communities kept together. As was repeatedly pointed out to us by the people we interviewed, what is at stake is not just the destruction of concrete and steel, but the destruction of home and of a sense of being and identity. It is about the protection and preservation of networks of friends and family and of a whole way of life, things that are beyond quantification or monetary value.

The Mayor’s Office brushes such criticism aside and using all the tricks of modern media has launched a propaganda campaign to win hearts and minds. Websites offer glimpses of utopia in carefully choreographed animations that depict wondrous green landscapes inhabited by young smiling families, birds, bicycles and blue skies. They have even built show homes kitted out with state of the art interiors to underline how all of this is being done in the best interests of the population. Predictably the demolition programme was unanimously approved by the Moscow Duma and it was quickly followed by the June 2017 law that declared that if two thirds of the residents of an apartment block voted yes then it would be scheduled for demolition and they would be given a flat in one of the new high rise towers. For those who are unemployed or on low incomes, and have been unable to invest in the upkeep of their homes after the wholesale privatisation of the housing stock in the 1990s, the offer of a modern apartment seems a fantastic proposition and they have naturally enough voted yes in their thousands. However, this means that neighbours who are unconvinced by the mirage of a new life and who voted no, will be given ninety days notice to vacate their homes or face the prospect of being forcibly evicted. They will also have no choice of where to live and some fear that they will end up out beyond the periphery in one of the new speculatively built towers that lie empty. This brings us to the other side of the story.

What for the Majors’ office is a legitimate attempt to clean up the city and to rid it of buildings past their sell by date, for others is nothing more than the appropriation of property as part of a multi-billion ruble exercise in real estate speculation. Location is everything and a feature of all the flats that we visited and which are scheduled for demolition is that they are well connected to the city’s infrastructure, and in close proximity to hospitals, schools and shops. They thus sit on potentially valuable land, the ownership of which post demolition is transferred to construction companies and banks. What is also significant is that the apartments in question are for the most part structurally sound, in a good state of repair, and richly decorated. In some cases they have been a family home for over three generations and therefore full of irreplaceable memories.

The sense of anger and frustration then at the usurpation of democracy and the naked political and economic ambitions of those in charge of the construction programme is palpable. Over the last year there has been a string of street protests in which people have brandished banners that speak of the ‘violation of the constitution’ and which use the highly emotive word ‘deportation.’ The group ‘Muscovites Against Demolition’ boasts over twenty eight thousand members and continues to monitor the sorry tale on a daily basis, pointing out that not only is perfectly good housing being demolished, but that over one hundred historically important architectural monuments have been destroyed as part of the process. If this is not bad enough, lawyers have expressed concern about the lack of judicial protection for opponents to demolition, the circumvention of planning laws, and the infringement of housing codes. Meanwhile engineers maintain that building regulations in some of the new tower blocks are being ignored with regards to natural light and the proximity to other buildings, and space standards are being reduced. There have also been questions raised about the structural stability of some of the high rises that are being hastily built in flood zones and on former industrial sites. In one case a block had to be evacuated almost immediately after completion because of construction faults.

Of course the process of real estate speculation and of decanting and dispersing communities is hardly unique to Moscow. It has been going on since the credit fuelled speculative frenzy of Haussmann’s reconstruction of Paris after the 1848 revolution and its essential mechanisms are features of neo-liberal urban development wherever it takes place. This means that a crisis triggered by the over production of property is a real threat and perhaps the only thing short of a mass uprising that will bring the demolition programme to a halt. The one sure thing about a construction boom is that it is followed by a slump. When the quantity of housing exceeds market demand, the value of real estate falls. This remains a real possibility. However, in a city that has always possessed a marked hallucinatory and surreal character, and in a country where nothing is ever done in half measures, whether that is pouring vodka, writing a thousand page novel or reversing the flow of rivers, the only certainty is that anything is possible.

|

|

Read next: Housing Crisis: New Frontiers

Read previous: Interior Report: Fitting Tribute

Back to April 2018

Browse Features Archive

Search

News

For more news from the industry visit our News section.

Features & Reports

For more information from the industry visit our Features & Reports section.